Nanshe (also known as Nanse, Nazi) is the Sumerian goddess of social justice and divination, whose popularity eventually transcended her original boundaries of southern Mesopotamia toward all points throughout the region in the 3rd millennium BCE. She became one of the most popular deities of the Mesopotamian Pantheon for her selfless devotion to the good of humanity.

She watched over orphans and widows, oversaw fairness, fresh water, birds and fish, fertility, and favored prophets, giving them the ability to interpret dreams accurately. She was also known as the Lady of the Storerooms and, in this capacity, made sure that weights and measures were correct. It was originally in this role, connected to commerce, that her popularity grew.

She was the daughter of Enki, god of wisdom and fresh water, and Ninhursag, the Mother Goddess (though she is also referenced as the daughter of Enlil). In some myths, she is sister to Nisaba, goddess of writing, and the hero-god Ninurta and, in others, the sister of Inanna and Ereshkigal. Her consort was Haia, god of storerooms, and her vizier was Hendursag who was in charge of judging people's deeds and transgressions.

Her husband/consort was originally Nindara, Hendursag's older brother, the local god of Lagash, known as a great warrior and the 'tax collector of the sea,' though the meaning of the epithet is unclear. However, she is most commonly associated with Haia. Nanshe was especially concerned for refugees fleeing war-torn regions, and these found sanctuary at her Sirara temple in the town of Nina, city of Lagash.

She is depicted on a cylinder seal as a woman dancing above water flanked by two winged Anuna (gods of the earth) with the winged solar disc above her (the Assyrian symbol of Utu-Shamash, god of justice). Enki gave her the responsibility for the waters of the Persian Gulf and all the creatures who dwelt therein, and she is frequently referenced in connection to water. She is also represented by the symbol of the fish and the pelican; the fish connects her with water but also symbolizes life, while the pelican, who, in legend, is said to sacrifice itself to feed its young, symbolized her devotion to humanity.

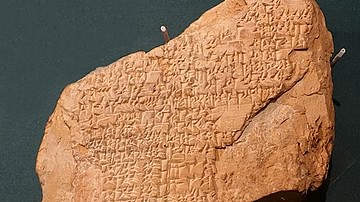

In all the inscriptions and hymns which mention her, Nanshe is portrayed as kind, compassionate, welcoming, and wise. She is probably best known from the Gudea Cylinders, two terracotta cylinders of the text The Building of Ningirsu's Temple, dated to c. 2125 BCE, in which she interprets the dream of Gudea, governor of Lagash (c. 2144-2124 BCE), and encourages him to build a temple for his god.

Nanshe's Origin in Myth

The in the myth Enki and Ninhursag, the two deities become lovers while staying in the land of Dilmun (a region of fertility and peace near the Persian Gulf). Ninhursag must return to her duties back home, and Enki, left alone, has an affair with their daughter, then her daughter, and then her daughter before he also must leave. This youngest daughter, Uttu, complains of her ill treatment to Ninhursag who advises her to wipe Enki's seed from her body and bury it in the ground. She does so, and beautiful plants spring from the earth.

When Enki returns to Dilmun with his vizier Isimud, he sees the plants and wants to taste them, eventually eating them all. Ninhursag finds out and curses Enki with the eye of death and then deserts the realm of the gods for a far off sanctuary. Enki falls ill and is near death when Ninhursag returns. She draws him to her and asks where his pain is. Each time he answers, she draws the pain into her own body, transforms it into something good, and gives birth, one by one, to eight deities who will benefit humanity:

- Abu (god of plants and growth)

- Nintulla (Lord of Magan, a region associated with copper and diorite)

- Ninsitu (goddess of healing, consort of Ninazu, the god of healing)

- Ninkasi (goddess of beer)

- Nanshe (goddess of social justice and divination)

- Azimua (goddess of healing and fertility, wife of Ningishida of the underworld)

- Ninti (goddess of the rib, she who gives life)

- Emshag (Lord of Dilmun and living things)

Of these eight, Ninkasi and Nanshe would become the best known and most often venerated.

Goddess of Justice

Her name spread through commerce, owing to her concern for justice and fair play. She made sure that weights and measures were correct and no one was cheated in the marketplace. In ancient Mesopotamia, if one wanted a certain amount of grain, it was placed on a scale balanced against a certain amount of weight to determine the price. These weights could be toyed with to reflect a different gauge than they actually were and so cheat a customer in paying more for less.

Nanshe was invoked as protection against such practices and also in swearing oaths that one was trading fairly. Once one had sworn, it was in one's best interests to keep that oath because, although Nanshe was a kind goddess, she would not hesitate to vent her wrath on those who displeased her through transgressions. A part of one of her hymns lists those who may expect to suffer at her hands:

People who, walking in transgression, reached out with a high hand

Who transgress the established norms, violate contracts

Who looked with favor on the places of evil

Who substituted a small weight for a large weight

Who substituted a small measure for a large measure

Who, having eaten something not belonging to him, did not say "I have eaten it"

Who, having drunk, did not say "I have drunk it"

Who said, "I would eat that which is forbidden

Who said, "I would drink that which is forbidden.(Kramer, 125)

The same hymn also describes those Nanshe cares for. Nanshe is the goddess who looks after the forgotten, the poor, the lonely, and disenfranchised.

[Nanshe is she] who knows the orphan, who knows the widow

Knows the oppression of man over man, is the orphan's mother

Nanshe, who cares for the widow

Who seeks out justice for the poorest

The queen brings the refugee to her lap

Finds shelter for the weak.(Kramer, 124)

In this capacity, she was linked with Utu-Shamash, the Sumerian/Akkadian god of justice represented by the sun. Just as the sun saw all things on the earth below as he crossed the sky, so too did Utu-Shamash. Nanshe, however, was much more accessible.

Worship of the Goddess

Nanshe was worshiped from the 3rd millennium BCE throughout Mesopotamia's history and into the Christian era. Her symbols of the fish and the pelican, in fact, were appropriated by the early Christians for their god. Nanshe's temple at Lagash was more than just a place of worship. Hymns from the time of Gudea describe her priestesses and priests feeding the poor, caring for the sick, looking after the orphan and widow, and involved in social justice on other levels.

On the first day of the new year, a great festival was held at her temple which people from all across the land attended. They would first ritually cleanse themselves and then submit to the Ordeal. The Ordeal was a common practice in ancient Mesopotamia whereby guilt or innocence was established by the gods through the simplest means: the accused was thrown into a river, and if they survived, then they were innocent.

Visitors who wished an audience with Nanshe to settle some legal dispute or gain a vision of the future had to submit to the Ordeal before entering the temple complex. It is unclear whether every visitor who came to the festival had to do likewise, but most likely they did not. Those who came asking for a vision of the future or dream interpretation, however, had to be pure in heart for Nanshe to receive them and would certainly have had to prove themselves free of sin. The most famous recipient of Nanshe's benevolence was the governor of Lagash, Gudea, who did not need to submit to the Ordeal to consult her because of his great devotion to the gods and their will.

Gudea's Dream Vision

Gudea is the best-known Mesopotamian ruler even though most people do not know his name. His piety and work in preserving the literary and religious traditions of Sumer, in addition to his efforts in temple building, elevated him to such a high status in his lifetime that he was worshiped during the later Ur III Period (2047-1700 BCE) as a god. Even if one has never heard his name, if one has even a nodding acquaintance with Mesopotamian art, one has seen the statue of the robed man, hands clasped, praying; that is Gudea. While there are many such statues depicting different Sumerian men and women at prayer, Gudea's is the most often featured in modern day publications.

In one of the most complete and compelling Sumerian texts extant, Gudea recorded a dream in which the god of the city of Lagash, Ningirsu (later known as Ninurta) came to honor him by asking for a temple. The dream vision is given as though the events took place in his waking life and is here given in translation with commentary by the Orientalist Samuel Noah Kramer:

In the dream, Gudea saw a man of tremendous stature with a divine crown on his head, the wings of a lion-headed bird, and a "flood wave" as the lower part of his body; lions crouched to his right and left. This huge man commanded Gudea to build his temple, but he could not grasp the meaning of his words. Day broke - in the dream - and a woman appeared holding a gold stylus and studying a clay tablet on which the starry heaven was depicted. Then a 'hero' appeared holding a tablet of lapis lazuli on which he drew a plan of a house; he also placed bricks in a brick mold which stood before Gudea together with a carrying basket. At the same time a specially bred male donkey was impatiently pawing the ground.

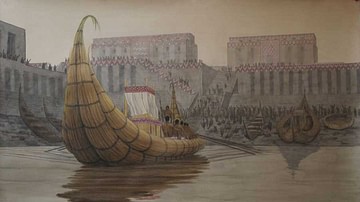

Since the meaning of the dream was not clear to him, Gudea decided to consult the goddess Nanshe, who interpreted dreams for the gods. But Nanshe lived in a district of Lagash called Nina, which could best be reached by canal. Gudea therefore journeyed to her by boat, making sure to stop at several important shrines along the way to offer sacrifices and prayers to their deities in order to obtain their support. Finally the boat arrived at the quay of Nina, and Gudea went with lifted head to the court of the temple where he made sacrifices, poured out libations, and offered prayers. He then told her his dream and she interpreted it for him point by point, thus:

The man of tremendous stature with a divine crown on his head, the wings of a lion-headed bird, a flood wave as the lower part of his body, and lions crouching to his right and left - that is [my] brother Ningirsu, who commanded [you] to build the temple eninnu. The breaking of day over the horizon - that is Ningishzida, Gudea's personal god, rising like the sun. The woman holding a gold stylus and studying a clay tablet on which the starry heaven was depicted - that is Nisaba (the goddess of writing and the patron deity of the edubba), who directs you to build the house in accordance with the "holy stars". The hero holding a tablet of lapis lazuli - that is the architect god Nindub drawing the temple plan. The carrying basket and brick mold in which "the brick of fate" was placed - these betoken the bricks for the Eninnu temple. The male donkey pawing the ground impatiently - that, of course, is Gudea himself, who is impatient to carry out his task. (138-139)

Gudea woke from his dream and, after prayer and sacrifice thanking Nanshe, reported his dream vision to his people and asked for their support. They responded with great enthusiasm, and the poem detailing the vision ends with the completion of the Temple of Ningirsu at Larsa.

The Gudea Cylinders present Nanshe as the wise and helpful goddess so many people of Mesopotamia responded to, and hymns and other inscriptions are consistent in this depiction. In the myth Enki and the World Order, to name only one, Nanshe is contrasted with her sister Inanna quite favorably. Even though Inanna was the most popular goddess in Mesopotamia, she is frequently depicted as a spoiled brat throwing a temper tantrum until she gets what she wants, and in Enki and the World Order, she is seen in exactly this way.

After Enki has created the world and assigned a place and function to every living thing, including the gods, Inanna confronts him complaining that everyone else has greater gifts than she does. She mentions Nanshe toward the end of her rant, pointing out the wonderful aspects given to her but denied to Inanna. Enki's response is, "What did I keep from you? What more could we add to you?" before listing all of the very impressive attributes she has already been given. Throughout Inanna's tirade, Nanshe is notably silent, as are the rest of the gods. Inanna does not need for them to judge her because her own angry words of ingratitude, and Enki's gentle response, have done that already.

Nanshe as Comforter and Companion

Unlike Inanna or even Enki, Nanshe has no myths in which she is depicted as petty, selfish, or thoughtless. She is consistently a defender of the disenfranchised, companion to the outcast, the poor, the sick, widows, orphans, and foreigners seeking refuge in a strange land. She is companion to the traveler and stranger and a friend to all in her community. One of her hymns makes clear that her central role was:

To comfort the orphan, to make disappear the widow

To set up a place of destruction for the mighty

To turn over the mighty to the weak

Nanshe searches the heart of the people.(Kramer, 125)

If this were so, one might ask, why was the goddess so popular when it was as obvious in ancient Mesopotamia as it is today that orphans and widows and refugees are not always cared for, quite often are not, and the mighty who care for no one but themselves and their own personal interests are not turned over to the weak nor do they seem to fear any imminent destruction.

The answer for the people of Mesopotamia was that, even though Nanshe meant them only the best, some other god or demon or spirit could have other plans in mind. The best one could do was place one's trust in the goddess, appeal to her in times of need, give thanks and rejoice with her in times of plenty, and simply hope that the power of Nanshe would prevail over the forces of darkness and despair. The most effective way to ensure this outcome, of course, was to work for the values Nanshe embodied, calling on her for protection and guidance, and trying to spread her light in one's daily life.