Of all the careers that soared to meteoric heights during the chaotic decade of the French Revolution (1789-1799), none was more spectacular nor impactful than that of Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821). From an unremarkable birth into minor Corsican nobility, Napoleon would find in the Revolution a path to fame, military success, and ultimately, to his role as Emperor of the French.

A quick glance at his career would be enough to show how intertwined his fate would become with the Revolution. His promising performance at the Siege of Toulon in 1793 would lead to his brilliant command of the Army of Italy, which in turn would help provide him with enough popularity and influence to seize control of the government in the Coup of 18 Brumaire, the event which many scholars consider to be the end of the Revolution. To understand this version of Napoleon, it is necessary to look at the person he was at the start of the Revolution; hardly the picture of a dashing military commander or French patriot, the Napoleon of 1789 was a thin, awkward man who did not yet even consider himself French.

Indeed, in 1789, 20-year-old Napoleon was in something of an identity crisis, looking to reconcile his ambitions of literary fame with his education as a soldier, his devotion to French revolutionary ideals with his Corsican nationalism. The early Revolution was undoubtedly a time of personal development for the young artillery lieutenant, the outcome of which would not only affect his own future but also the fate of all of Europe.

The Corsican

In 1768, the year before Napoleon's birth, the Kingdom of France purchased Corsica from the Republic of Genoa, which had distantly ruled it for the previous few centuries. Although nominally under Genoese control, the Corsicans had been used to effectively ruling themselves. They had recently claimed independence, declaring the Corsican Republic in 1755, but such aspirations to self-rule would come to an end with the arrival of the French. In Napoleon's own words, he was born "as the fatherland was dying. Thirty thousand Frenchmen, vomited upon our coasts, drowning the seat of liberty in torrents of blood" (Bell, 18).

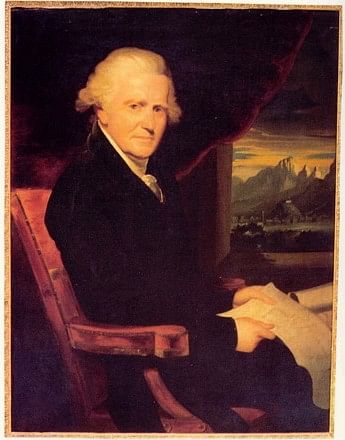

There was resistance, of course. Led by Pasquale Paoli (1725-1807), the Corsicans were initially successful at beating back the French Expeditionary Force that landed on their shores in 1768. However, this success would not last, as the French had the advantage in manpower and supplies; the French victory at the Battle of Ponte Novu in 1769 destroyed the Corsican will to fight. Although sporadic guerilla warfare continued, Paoli fled to Britain, and Corsica was annexed by France.

Although this defeat was lamented by many Corsicans, some were able to take advantage of this regime change. Napoleon's father, Carlo Buonaparte, was one of them. A former ally of Paoli, Carlo chose to abandon the patriotic cause to ensure a future for his family. His gamble paid off, as Carlo's devotion to the new government allowed him to secure minor nobility status for his family under French law, which in turn allowed him to send his oldest sons to receive education in French royal academies. Because of his father's change in loyalties, ten-year-old Napoleon was educated at the military academy of Brienne in northern France, where he learned French and excelled in mathematics. Paoli, however, would not forget nor forgive Carlo's apparent betrayal.

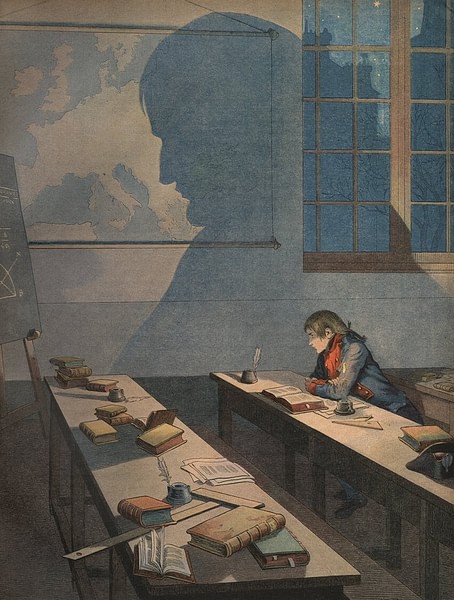

Despite reaping the benefits of French occupation, teenaged Napoleon remained a staunch Corsican nationalist. He idolized the exiled Paoli as a freedom fighter and clung to dreams of an independent Corsica. Such a demeanor, along with his strange accent and difficult-to-pronounce name (recorded in the school registry as Neapoleonne Buonaparte), quickly alienated Napoleon from his French classmates. Much of his time was spent alone, and he would soon develop a “thoughtful and gloomy” nature, according to his headmaster (Roberts, 11). Lacking companions, Napoleon would find company amongst his books. He adored poetry and history, although he also took an interest in the Enlightenment philosophers, who were so popular at the time. He became especially fond of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, perhaps because of Rousseau's own support of the Corsican plight. Napoleon adopted many of Rousseau's ideas, which would soon become the same ideas that fueled the Revolution.

In 1786, the year after he graduated from the prestigious Ecole Militaire as an artillery lieutenant, 16-year-old Napoleon embarked on something of a literary career. An exceptionally ambitious young man, it did not seem likely that he, as a Corsican-born man of minor nobility, would amount to much in the French army. To compensate, Napoleon sought literary glory instead. Over the next ten years, he would write over 60 essays, novellas, and letters. His first known essay, written on 26 April 1786, argued that Corsica had an undeniable right to resist the French, while a follow-up essay entitled On Suicide was an interesting mixture of nationalistic pride and teenaged angst:

My fellow countrymen are weighed down with chains, while they kiss with fear the hand that oppresses them…you Frenchmen, not content with having robbed us of everything we hold dear, have also corrupted our character. A good patriot ought to die when his fatherland has ceased to exist. (Roberts, 22)

Although borderline treasonous, especially for an enlisted officer in the French army, Napoleon continued espousing his nationalism in his writings over the next few years. He spent months, on and off, writing a comprehensive history of Corsica, in which he compared his countrymen to the virtuous ancient Romans, while also penning a novella entitled New Corsica, which was, in the words of biographer Andrew Roberts, little better than a graphic "Francophobic revenge fantasy" (Roberts, 31). He would find little publication luck, and for a time, it appeared the young artillery lieutenant may be doomed to literary as well as military obscurity.

Then, in 1789, the course of history shifted. The Estates-General of 1789 declared themselves a National Assembly, wresting authority from the king. In July, the commoners took matters into their own hands with the Storming of the Bastille. The French Revolution had begun.

The Revolutionary

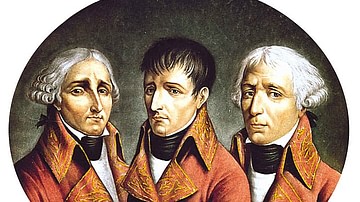

Despite his obligations as a French officer, Napoleon welcomed the Revolution, viewing it as a manifestation of the Enlightenment ideals he had come to believe in, a triumph of logic and reason. Still, he did his soldierly duty and helped disperse a riot in Auxonne eight days after the Bastille fell, arresting 33 people. In August, he received permission to return to Corsica on sick leave. Back in the Corsican capital of Ajaccio, Napoleon was reunited with his brothers, Joseph and Lucien, the latter of whom was already a staunch supporter of radical revolutionary politics at the age of 14. The Bonapartes became outspoken revolutionary supporters in Ajaccio, sporting the tricolor cockade in their hats and signing their letters with the obligatory "citizen".

In early 1790, the Bonapartes would be endeared even closer to the revolutionary cause when the National Assembly proclaimed Corsica to officially be a department of France. Subject to French laws, Corsicans would now reap the benefits of citizenship, and to make matters even better, the Assembly declared that Corsica would henceforth be governed solely by Corsicans. At the same time, they invited Paoli to return from his 22-year exile. Napoleon was ecstatic, as evidenced by the huge banner that hung from Casa Bonaparte, which read "Vive la Nation! Vive Paoli!" (Roberts, 33).

Not every Corsican was thrilled with these developments, however, with no one less happy than Napoleon's hero Pasquale Paoli himself. The aged freedom fighter saw in the Assembly's decree nothing but an attempt by Paris to further impose its will on the island. He saw in the Bonaparte brothers nothing but the children of a French collaborator. Carlo Buonaparte may have been dead, but by the way his children were celebrating the Paris government, Paoli considered them no better. He refused to support Joseph Bonaparte's campaign for deputy to the Corsican assembly, and he was further offended by a pamphlet written by Napoleon, which derided many of the returned Corsican exiles for their preference for a constitution in the style of Great Britain rather than for the constitution currently being developed by the Assembly. Because of this pamphlet, Paoli passive-aggressively refused Napoleon's request to write the dedication for his history of Corsica and even refused to read the manuscript, using the excuse that "history should not be written in youth" (Roberts, 34). Napoleon's dreams of literary success were again frustrated, this time by his childhood hero.

After briefly returning to duty in France, Napoleon came back to Corsica in early 1792 to stand for election as a lieutenant colonel in the Corsican National Guard. It was a dirty and dramatic election, filled with bribes and even the temporary kidnappings of election officials. Paoli supported Napoleon's opponent, but Napoleon had the support of Antoine-Christoph Saliceti, who represented the National Convention on Corsica (the Convention having succeeded the National Assembly as France's governing body). With the support of Paris, Napoleon won the election and the lieutenant colonelcy.

Not long after Napoleon won his post, Saliceti gave the order for all monasteries and convents in Ajaccio to be stripped, the proceeds to be shipped to fund the treasury of the central government in Paris. This was met with outrage by the Catholic citizens of Ajaccio, who rioted on Easter Sunday 1792. It fell to Napoleon to suppress the revolt. The bloody struggle would last four days, in which one of Napoleon's lieutenants was even shot dead at his side. During the confusion, Napoleon apparently tried unsuccessfully to capture the town's fortified citadel, which was garrisoned by French regular troops. Paoli, seeing an opportunity to rid himself of the troublesome colonel, wrote to the war ministry in Paris, accusing Napoleon of treason. Fortunately for Napoleon, nothing ever came of the matter, as the war ministry had other things to worry about; on 20 April 1792, France declared war on Austria and Prussia and invaded the Austrian Netherlands.

The Jacobin

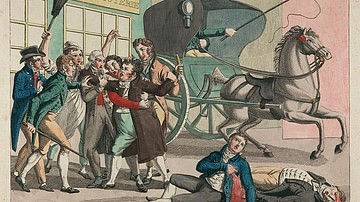

Napoleon could not stay in Ajaccio following the Easter Sunday debacle, so he returned to Paris, hoping to resume his commission in the army. He was in the city during the Demonstration of 20 June 1792, when a Parisian mob stormed the Tuileries Palace, accosted King Louis XVI of France and Queen Marie Antoinette, and forced the king to wear the red cap of liberty atop the palace balcony. Although he had no respect for the monarchy, Napoleon hated mobs and wondered why the king and his guards had allowed the mob to humiliate them without a fight. According to his friend Bourrienne, Napoleon apparently remarked, "What madness! How could they allow that rabble to enter? Why do they not sweep away four or five hundred of them with cannon? The rest would take themselves off very quickly" (Roberts, 39).

He was still in Paris that September when more than 1,200 people were murdered in the city's prisons in the September Massacres. These massacres, a reaction to Prussia's and Austria's threat to destroy Paris, were defended by Napoleon, who stated, "I think the massacres…have produced a powerful effect on the men of the invading army. In one moment, they saw a whole population rise up against them" (Roberts, 40). These words found him inching closer to Jacobinism, an ideology already fully embraced by his brother Lucien, who went by the alias "Brutus" in the Corsican chapter of the Jacobin Club.

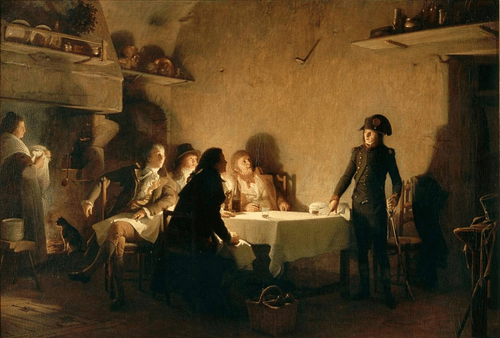

In 1793, he wrote a pamphlet entitled Le Souper de Beaucaire, an account of a fictional dinner in the village of Beaucaire. Taking the form of a discussion between himself and a group of disgruntled merchants, the pamphlet argues that France was in existential danger and that the Jacobin government had to be supported, lest vengeful aristocrats engulf the nation. The pamphlet, which marked Napoleon as a true sympathizer of the Jacobin cause, caught the attention of Augustin Robespierre, younger brother of the more famous Jacobin leader, who arranged for its publication. This was a turning point in Napoleon's career, giving him valuable connections.

He returned to Corsica in late 1792, just after the declaration of the First French Republic, to champion the Jacobins' cause. His return found the island even more anti-French than when he had left it, as many had become alienated by the Revolution's policies of dechristianization and by the September Massacres. Napoleon, meanwhile, was fully on the side of the Revolution. As biographer Roberts explains:

He moved from being a Corsican nationalist to a French revolutionary not because he finally got over being bullied at school, or because of anything to do with his father…but simply because the politics of France and Corsica had profoundly changed and so too had his place within them. (41)

Around this time, he gave up writing history and fiction, stating that he no longer had "the small ambition to become an author" (Bell, 19). The Revolution had given him a new purpose. In February 1793, a month after the execution of King Louis XVI, Napoleon was given his first true military command. His task was to liberate three small Sardinian islands from the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia, which had recently joined the quickly expanding list of France's enemies. He had been selected by Paoli, who was perhaps secretly hoping he would fail – far from the 10,000 men the Paris Convention requested for the expedition, Paoli had furnished Napoleon with only 1,800. This was not nearly enough to complete the task, and Napoleon was forced to return to Corsica in defeat.

By now, the break between Paoli's supporters and the Convention was inevitable; indeed, Paoli's loyalties were drifting closer to Great Britain, his old hosts during his exile. Yet, even now Napoleon tried to reconcile his loyalty to his homeland with his newfound identity as a French revolutionary. But when Saliceti ordered Paoli's arrest for treason, his supporters rose in revolt against the Jacobin regime. Napoleon realized a decision had to be made. He chose the Republic.

The Soldier

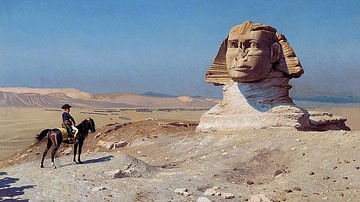

On 3 May 1793, Napoleon was detained by Paolist supporters on his way to join his brother Joseph in Bastia. He was freed soon after by villagers sympathetic to France, although the family estate, Casa Bonaparte, was ransacked by Paolists a few weeks later. Having seized the city of Ajaccio, Paoli's government officially outlawed the Bonaparte family. A despondent Napoleon finally denounced his childhood hero, writing that Paoli had "hatred and vengeance in his heart" (Roberts, 44). With few options, the entire Bonaparte family left Corsica on 11 July 1793 aboard the ship Proselyte, landing at the French port city of Toulon two days later. By the end of the month, Paoli recognized King George III of Great Britain as the ruler of Corsica. Save for a brief pitstop on the island in 1799 on his return voyage from campaigning in Egypt, Napoleon would never see Corsica again.

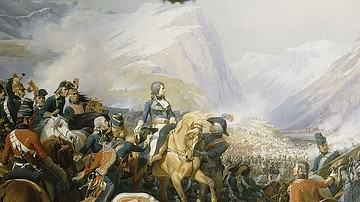

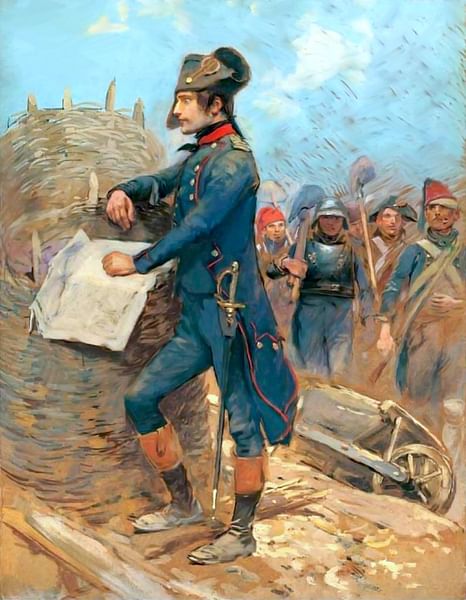

It would not take long for Napoleon's Jacobin connections to pay off. On 24 August, a combined Coalition army of British, Spanish, and Neapolitans occupied Toulon at the invitation of the fédéré rebels who had revolted there. Due to his friendship with major Jacobin figures such as Saliceti and Augustin Robespierre, and because the army had been depleted by mass emigrations and executions, Napoleon was immediately given the rank of major in the army that was sent to retake the city. By October, he was in command of all the artillery involved in the siege. His brilliant and daring actions during the Siege of Toulon became the first chapter of the Napoleonic legend; he played a huge role in the city's fall in December. For his actions, he received the rank of brigadier-general on 22 December, at the age of just 24.

Using his newfound influence, Napoleon submitted a plan for the invasion of Italy to the Committee of Public Safety in early 1794. It was supported by Augustin Robespierre, who was overseeing the Italian theater of war, and who had helped get Napoleon appointed as the artillery commander of the Army of Italy. That July, Napoleon embarked on secret missions to Genoa on Robespierre's behalf, in the hopes of becoming closer integrated into the Jacobin leadership. It was the worst possible time he could have done this. That month, the Thermidorian Reaction led to the downfall and execution of top Jacobin leaders, including the Robespierre brothers. Due to his relationship with Augustin, Napoleon was arrested on 9 August in Nice.

Had Napoleon been in Paris when the Jacobins lost power, he very well could have been guillotined along with his former patron. Instead, he was released on lack of evidence on 20 August. While other former Jacobins may have wished to slide into obscurity following such a close call, Napoleon was still a man of insatiable ambition. His exploits soon caught the eye of one of the new Thermidorian leaders, Paul Barras, who tasked Napoleon with putting down an uprising in Paris. Napoleon executed this task, the revolt of 13 Vendemiaire, with calculated efficiency, the famous "whiff of grapeshot", elevating his position further. In March 1796, partly thanks to the efforts of his new patron Barras, Napoleon was given command of the Army of Italy. Napoleon's First Italian Campaign would be the decisive moment in the War of the First Coalition, and would also set Napoleon on his trajectory toward the throne.