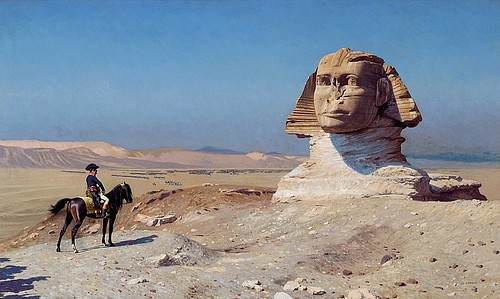

The French Expedition to Egypt and Syria (1798-1801), led by Napoleon Bonaparte, aimed to establish a French colony in Egypt and to threaten British possessions in India. Despite initial French victories, the campaign ultimately ended in failure, and Egypt remained under Ottoman control. The expedition also led to the discovery of the Rosetta Stone and the birth of modern Egyptology.

A New Alexander

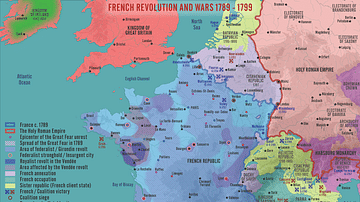

By the end of 1797, the French Republic was dominant in Western Europe, having defeated almost all its enemies in the War of the First Coalition. Only Great Britain remained at war; despite half-hearted overtures for peace in 1797, the British now displayed a renewed determination, as Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger looked to bankroll a second anti-French coalition. The French Directory, the government of the Republic, was equally determined to see the war to its conclusion and assembled a 120,000-man army for a daring invasion of Britain. Command of this Army of England was given to General Napoleon Bonaparte, who set out on a rapid tour of the dockyards to assess the feasibility of such an expedition. His disheartening conclusion was that British naval superiority doomed any attempted invasion to failure. Instead, Bonaparte offered an alternative path to victory, suggesting that the French could threaten Britain's empire by establishing a colony in Egypt.

French ministers had been toying with the idea of a French colony in Egypt since the 1760s, but the Directory's desire to defeat Britain made it particularly appealing now. The Directory desperately needed to recoup the loss of its colonies in the West Indies, and the rumored wealth of Egypt would make it a fine addition to France's struggling colonial empire. Egypt's location also made it the perfect base from which the French could menace British interests both in the Mediterranean and in India, and Bonaparte suggested opening communications with anti-British elements in India like Tipu Sultan. The Directory even saw the benefits of a defeat, as it would rid them of the troublesome General Bonaparte, whose rising popularity made him a threat. The insatiably ambitious Bonaparte, of course, had motives of his own, wishing to emulate his hero Alexander the Great and build an eastern empire. "Europe is a molehill," Bonaparte once remarked, "all the great reputations have come from Asia" (Roberts, 159).

Seeing no downsides, the Directory approved the expedition on the condition that Bonaparte raise the necessary funds himself and that he return to France within six months. Almost immediately, Bonaparte procured the needed 8 million francs, securing 'contributions' from France's sister republics in Holland, Switzerland, and Italy. Bonaparte selected 21 of the finest demibrigades in France, amounting to some 38,000 soldiers. He also filled his officer corps with some of the most talented generals in the French army. Alexandre Berthier returned as his indispensable chief of staff, while division commands were held by experienced generals Jean-Baptiste Kléber, Louis Desaix, Louis-Andre Bon, Jean Reynier, and Jacques Menou. Bonaparte even brought along his stepson Eugene de Beauharnais and brother Louis as aides-de-camp.

Hoping to give the expedition a scientific purpose as well, Bonaparte secured the services of 167 of the most distinguished scientists and scholars in France; directed by mathematician Gaspard Monge, these savants were to conduct research and show off European scientific advances. The presence of these savants would lead to the discovery of the Rosetta Stone and the birth of modern Egyptology.

Capturing Malta

As the French expedition gathered in Toulon, neither soldier nor savant knew where they were headed; the Royal Navy's control of the Mediterranean meant that discretion was of the utmost importance. In early May 1798, a French armada under Vice-Admiral Brueys gathered to ferry the new Armée d'Orient to Egypt; the fleet consisted of 13 ships-of-the-line, 13 frigates, and over 200 transports. A fleet of such enormous size could not avoid the detection of English agents, and by the time the expedition set sail on 19 May, a squadron of British warships under Horatio Nelson was prowling the Mediterranean in search of it. However, luck was on the side of the French fleet; on 21 May, a severe gale dismasted Nelson's flagship and scattered his squadron toward Sardinia. After repairing his ships, Nelson sailed within 20 miles of the French fleet, which remained undetected thanks to thick fog.

The French made it to Malta without incident on 10 June. Bonaparte, wanting to secure the island before moving on to Egypt, ordered an invasion on the pretext that the island had shown hostility by not allowing his entire fleet to anchor. Although the Knights of St. John, the military order that controlled Malta, was famous for withstanding sieges, the island fell to the French after only minimal resistance, since half the knights were French and refused to fight their countrymen. After taking control of Malta, Bonaparte plundered its treasury and spent six days reforming Malta's administration; he expelled the Knights of St. John, abolished slavery and feudalism, reformed the hospital and university, and allowed the Jews to build a synagogue. Then he left behind a garrison and sailed for Alexandria on 19 June.

Campaigning in Egypt

The Ottoman Empire had ruled Egypt since 1517, though the centuries had seen the sultan's hold over the country slip. By 1798, Egypt was under the de facto rule of the Mamluks, a military caste originally from the Caucasus Mountains, who had imposed harsh taxes and were generally hated by their Egyptian subjects. Bonaparte hoped to present himself as a liberator, writing pamphlets claiming he had been sent by Allah to cast off Mamluk tyranny. To avoid hostilities with the Ottomans, Bonaparte had been assured that French foreign minister Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand would go to Constantinople to explain French purposes and promise the sultan that Egypt would continue paying him an annual tribute. Yet despite being the biggest supporter of the Egyptian expedition, Talleyrand never went to Constantinople; it would not be the last time he would betray Napoleon.

The French fleet arrived off the coast of Alexandria on 1 July, and Bonaparte disembarked at Marabut, 13 km (8 mi) away. The French assaulted Alexandria the next morning; General Menou stormed the Triangular Fort outside the city, while Kléber and Bon seized the Pompey and Rosetta gates. Driven by thirst, the French attacked with extra determination, and the city was in French hands by midday.

Bonaparte remained in Alexandria for a week before setting out for Cairo on 7 July, leaving the fleet anchored in Aboukir Bay and 2,000 men behind as a garrison. The ensuing march through the desert was brutal, and the suffering caused by scorching heat and mosquito swarms was worsened by lack of water; the wells along the route were poisoned or blocked up by Bedouin tribesmen. Many soldiers were afflicted by ophthalmia, which caused temporary blindness, and stragglers were picked off by the pursuing Mamluks. Discipline reached a critical low as several soldiers shot themselves and others plotted mutiny.

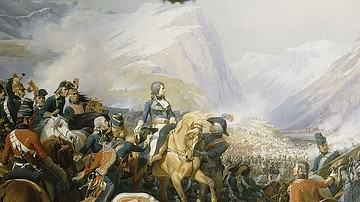

Morale improved on 10 July, when the army reached the Nile; delirious soldiers rushed into the muddy waters to drink, and several died from overindulgence. On 13 July, Bonaparte met and defeated a Mamluk army under Murad Bey at the minor Battle of Shubra Khit. Murad retreated only to gather new forces and reappeared on 21 July outside the town of Embabeh. The 20,000 Frenchmen seemed hopelessly outnumbered; Murad Bey commanded 6,000 mounted Mamluks and a militia force of as many as 54,000 fellahin or Arab peasants. Yet Bonaparte was undeterred. He formed each of his five divisions into a square, with cannons positioned on the corners. Alluding to the Great Pyramid of Giza, clearly visible from the field, Bonaparte told his men: "From the top of those pyramids, forty centuries look down upon you!" (Chandler, 224).

The ensuing Battle of the Pyramids was the most famous French victory of the campaign. The square formations made the formidable Mamluk cavalry useless, as the horses reared and threw off their riders when threatened with French bayonets. Within two hours, the Mamluks had been routed, and hundreds drowned in their panicked attempt to flee across the Nile. The Mamluks often rode into battle with all their valuables, meaning a single Mamluk corpse was enough to make a French soldier rich; for days after the battle, the French engaged in the macabre sport of fishing Mamluk corpses out of the river with bayonets. Murad Bey's co-ruler, Ibrahim Bey, abandoned Cairo without a fight, and Bonaparte entered the city in triumph on 24 July. General Desaix was sent to pursue Murad and Ibrahim into Upper Egypt, and Desaix covered himself in glory after defeating the Mamluks at El Lahun (7 October), Samhud (22 January 1799), and Abnud (8 March).

Bonaparte's good luck would not last forever. On 1 August 1798, Nelson finally caught up with the French fleet anchored at Aboukir Bay. In the resulting Battle of the Nile, the French armada was annihilated; 11 of the 13 ships-of-the-line were captured or destroyed, and the explosion of the French flagship L'Orient killed Admiral Brueys and 1,000 French seamen. The totality of Nelson's victory cut Bonaparte off from any supplies or reinforcements from France; the day after receiving the news, Bonaparte quipped to his officers, "It seems to me you like this country. That's very lucky, for now we have no fleet to carry us back to Europe" (Roberts, 178).

Occupation of Cairo

With much of Egypt under his control, Bonaparte attempted to win over the populace. In Cairo, he engaged the local sheiks in theological discussion, showing off his knowledge of the Quran and giving the impression that he meant to convert to Islam. On 20 August, he funded a three-day celebration of the Prophet Muhammad's birthday, during which he was declared a son-in-law of the Prophet and presented with the name Ali-Bonaparte. On the final day of the celebrations, Bonaparte inaugurated the Institut d'Egypte with Monge as its president, an attempt to impress the Cairenes with Enlightenment science and reason.

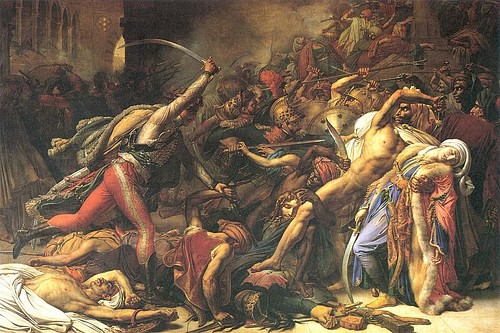

Many did not buy into this performance, and malcontent continued to fester beneath the French occupation. In September, Talleyrand's failure to live up to his end of the bargain became apparent as the Ottoman Empire declared war on France; on 20 October, word reached Cairo that the Ottomans were gathering an army in Syria to attack Bonaparte. That same night, Cairo erupted in revolt. General Dupuy, military governor of the city, was lanced to death in the street while 15 of Bonaparte's bodyguards and one of his aides-de-camp were murdered, their bodies fed to dogs. Before Bonaparte could launch a proper response, 300 French soldiers were dead, and the Cairene rebels had taken shelter in the Gama-el-Azhar Grand Mosque.

Aware that any delay would encourage more of Cairo's 600,000 citizens to join the uprising, Bonaparte responded with ruthlessness. He bombarded the Grand Mosque with artillery before sending in his infantry, who desecrated the building. 2,500 rebels were killed in the initial fight and over the coming weeks, hundreds more were executed. To save ammunition, Bonaparte had them beheaded, their heads piled in the center of the city, their bodies tossed in the Nile. By 11 November, the revolt had been quelled, and Bonaparte could turn his attention toward the rising threat in Syria.

Campaigning in Syria

Bonaparte decided to preempt the coming Ottoman invasion. In February 1799, he led 13,000 men out of Egypt, consisting of four depleted divisions under generals Reynier, Kléber, Bon, and Jean Lannes, with the cavalry led by Joachim Murat. On 17 February, Bonaparte was stopped by 2,000 Ottoman soldiers defending the fortress of El-Arish. The fortress fell two days later following a fearsome bombardment, and Bonaparte allowed the garrison to leave after swearing by the Quran that they would not return to fight against him. The French then passed through Gaza before moving on to begin the Siege of Jaffa on 3 March. The siege continued for three days, at which point Bonaparte sent a messenger to demand the city's surrender; Jaffa's governor beheaded the messenger and displayed the head on his walls. The next day, thousands of enraged Frenchmen stormed the city, and Bonaparte gave Jaffa over to 24 hours of unrestrained sacking. As one horrified savant recalled:

The sights were terrible. The sound of shots, shrieks of women and fathers, piles of bodies…the smell of blood, the groans of the wounded, the shouts of the victors quarreling over loot. (Roberts, 189)

The atrocities did not end there. Because some of the defenders of Jaffa were the same men that Bonaparte had released after taking El-Arish, the general decided to punish the entire garrison. On 9 March, between 2-3,000 prisoners of war were taken to a beach south of Jaffa, where they were all massacred. Bonaparte defended his actions by claiming he had not enough food to feed them, despite having just taken some 400,000 rations of biscuits from Jaffa. As biographer Andrew Roberts notes, there was a racial element to this massacre, as Bonaparte certainly would not have treated a surrendered European army with such cruelty.

In an interesting display of karmic justice, the French army was struck by bubonic plague shortly after the Jaffa massacres. With a mortality rate of 92%, there were 270 new cases a day; although Bonaparte did his best to visit the sick and care for his men, there was only so long he could linger in Jaffa. On 14 March, Bonaparte gathered his able-bodied soldiers and set out for Acre.

Siege of Acre

Bonaparte arrived outside Acre on 18 March to find the city formidably defended. The garrison was commanded by Jezzar Pasha, governor of Syria, whose ruthlessness had earned him the nickname "the butcher"; the Ottomans were supplied and reinforced by the wily British commodore Sir Sidney Smith, who had been waging psychological warfare against the French by denying them access to any news from France. Bonaparte remained confident in a quick victory until the flotilla carrying his heavy siege guns was captured by the enemy, and the French soon found themselves under fire from their own guns. Bonaparte was forced to resort to more time-consuming methods of siege warfare such as sapping.

This was only the first of a series of calamities to befall the besieging army. Bonaparte's initial assault on 28 March ended in disaster when the French ladders were discovered to be too short to scale the walls; Bonaparte ordered eight more major attacks over the following nine weeks, all of which ended in failure. The French siege lines also extended into mosquito-infested swampland, causing an outbreak of malaria. As the French casualties began to stack up, Bonaparte found that he was being deprived of his talented officers. The popular general Cafferelli succumbed to gangrene on 28 April, and General Bon was mortally wounded on 10 May. General Lannes and Eugene de Beauharnais were severely wounded.

On 16 April, the French defeated an Ottoman relief army at the Battle of Mount Tabor. Impressive though that victory was, it did little to improve Bonaparte's prospects of capturing Acre. Before long, Sidney Smith pulled off his greatest act of psychological warfare yet when he allowed one piece of true news to reach Bonaparte's army; this was a newspaper announcing the beginning of the War of the Second Coalition and the military defeats that had befallen France in Europe. Realizing his talents were needed back in Europe, Bonaparte lifted the siege on 20 May and began the long, demoralizing trek back to Cairo. The failure of the siege would always haunt Bonaparte, who later lamented, "I missed my destiny at Acre" (Roberts, 198).

Retreat

Arriving at Cairo on 14 June, Bonaparte gathered every available soldier and marched for Alexandria. By the time they arrived, Smith had ferried 15,000 Ottoman soldiers under Mustapha Pasha to Aboukir; on 25 July, Bonaparte engaged them at the Battle of Aboukir, which would turn out to be his last victory in Egypt. 2,000 Ottomans were killed in the battle with many more drowning as they were driven into the sea. The French lost less than 1,000 casualties, but with Brueys' fleet destroyed and France once again at war with Europe, it was clear no reinforcements were coming.

Having told no one of his intentions to leave Egypt, Bonaparte sailed away on 23 August with only a handful of officers and savants, abandoning the rest in Alexandria. Within 41 days, he was back in France, and by the end of the year, he had seized control of the French government in the Coup of 18 Brumaire.

Despite Bonaparte's claims that he was needed in Europe, the army he left behind understandably felt betrayed. No one was more furious than General Kléber, who inherited command of the disintegrating expedition; Kléber began referring to Bonaparte as 'that Corsican runt', promising to get revenge when he returned to Europe. Kléber would never get the chance, as he was assassinated in Alexandria in June 1800.

The command passed to General Menou, who was responsible for the defense of Alexandria when an Anglo-Ottoman army under Sir Ralph Abercromby attacked on 21 March 1801. Though Abercromby was mortally wounded, the Battle of Alexandria resulted in an Allied victory. Cairo fell in June, and Menou surrendered Alexandria on 2 September 1801 after a lengthy siege. The Treaty of Paris of 25 June 1802 ended hostilities between France and the Ottoman Empire, and Egypt fell once again under Ottoman control.