Slavery was practiced by the Native Americans before any Europeans arrived in the region. People of one tribe could be taken by another for a variety of reasons but, whatever the reason, it was understood that the enslaved had done something – staked himself in a gamble and lost or allowed himself to be captured – to warrant such treatment.

This model changed with the arrival of the Spanish in the West Indies in 1492 and their colonization of that region, South, and Central America throughout the 16th century. Native Americans were then enslaved simply for being Native Americans. In North America, after the English arrived, Native Americans were at first enslaved as prisoners of war but, eventually, were taken and sold to plantations in the West Indies to clear the land for expansion of English colonies.

This practice continued throughout the colonial era aided and encouraged by Native American tribes themselves up through 1750 and, after the American War of Independence (1775-1783), natives were pushed into the interior as African slavery became more lucrative. Even so, the enslavement of Native Americans continued even after slavery was abolished by the 13th Amendment to the Constitution in 1865. Americans got around illegal enslavement of natives by calling it by other names and justified it in the interests of "civilizing the savages". The practice continued up through 1900, dramatically impacting Native American cultures, languages, and development.

Native American Slavery & Columbus

Native American tribes were incredibly diverse, each with their own culture, and far from the cohesive, unified civilization they are often represented as under the umbrella term "Native American" or "American Indian". Each tribe understood itself as inherently superior to others and although they would form alliances for short periods in a common cause, or for longer periods as confederacies, they frequently warred with each other for goods, in the name of tribal honor, and for captives, among other reasons.

Men, women, and children taken captive were then enslaved by the victorious tribe, sometimes for life and other times for a given number of years and, in still other cases, until they were adopted and became members of the tribe. People could also be enslaved as hostages, held to ensure compliance with a treaty, and in some tribes, people were not only enslaved for life but any children born to them were also considered slaves, thereby creating a slave class long before the arrival of Europeans.

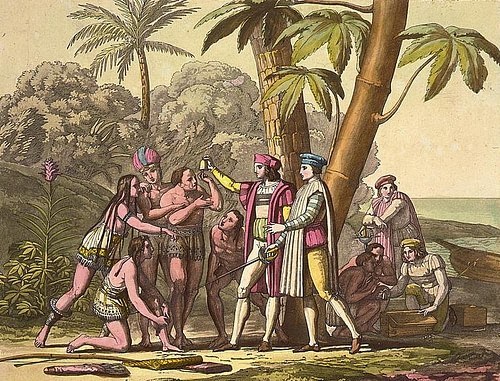

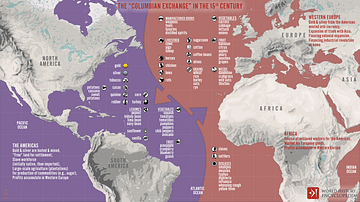

This model changed after the arrival of Christopher Columbus (l. 1451-1506) in the West Indies in 1492 and the Portuguese in 1500. Columbus kidnapped natives he brought back to Spain as slaves on his first voyage and sent over 500 back on his second. Between 1493-1496, he implemented the encomienda system, which institutionalized Native American enslavement throughout the Spanish colonies of the New World, and, by the time the French, Dutch, and English began colonizing North America, the Transatlantic Slave Trade was already established.

Jamestown & the Powhatan Wars

The French and Dutch initially tried to profit from the Native Americans by employing them as guides, hunters, fishers, and trappers, although their ships participated in the slave trade to the south. Only later on would they engage in the kidnapping and sale of the natives to Spanish plantations and other regions. When the English established the Jamestown Colony of Virginia in 1607, they took a completely different approach and expected the tribes of the Powhatan Confederacy to support them as the first colonists had no idea how to do that for themselves. Within three years of their arrival, the first of the Anglo-Powhatan Wars (1610-1646) had broken out and natives were enslaved as prisoners of war by c. 1610.

The First Powhatan War (1610-1614) ended when the English colonist John Rolfe (l. 1585-1622) married Pocahontas (l. c. 1596-1617), daughter of the Powhatan chief Wahunsenacah (l. c. 1547 - c. 1618) establishing the Peace of Pocahontas until the Second Powhatan War (1622-1626) broke out after the Indian Massacre of 1622. After these first two conflicts, the antagonists made peace and continued to engage in trade but after the Third Powhatan War (1644-1646) the Powhatan Confederacy was dissolved and many of its members were sold into slavery outside of the country.

Pequot War & First Large-Scale Enslavement

While Jamestown and its satellite colonies were developing, the English were establishing the New England Colonies to the north. Disputes over land and trade rights increased tensions between colonists and the Native American Pequot tribe in the 1630s eventually leading to the Pequot War (1636-1638) and the first evidence of wide-scale enslavement of Native Americans. Scholar James D. Drake comments:

Nothing makes the colonists' perception of Indians' inferiority more apparent than the mass selling of enemy Indians into slavery…Perhaps the English would not have resorted to enslaving enemy Indians had another commonly administered form of punishment, banishment, been logistically possible. New England Puritans had a history of banishing those individuals that they perceived as threats to their communities, for example, Roger Williams and Anne Hutchinson. But even in these cases, some wondered how much of a punishment banishment really was…Slavery, a more rigidly enforced type of banishment, therefore more closely approximated the punitive action taken against errant English men and women in the region. Forcing Indians into slavery or servitude also helped satisfy the dilemma of what to "do" with them [and] slavery and servitude had the additional advantages of helping to ameliorate a labor shortage in the New England colonies. (136-138)

After the Mystic Massacre of 1637, which effectively ended the war, many of the vanquished Pequots were given as slaves to the Mohegan and Narragansett tribes who had allied with the English, while others were enslaved on English farms and still others sold overseas. The English colony of Barbados, with its large sugarcane plantations, needed sizeable imports of slaves as most died within the first year or even the first few months, and a number of Pequots were sent there.

Native American Involvement in Slavery

Native American slaveholders overall treated their slaves far worse than the Europeans because the enslaved were thought to have lost their honor and human dignity by allowing themselves to reach such a deplorable state. It is unknown whether this was the paradigm prior to the arrival of Europeans or if they modeled their behavior on the colonists’ treatment of slaves. Either way, native tribes not only owned slaves but assisted colonists in acquiring more. Scholar Andres Resendez notes:

Native Americans were involved in the slaving enterprise from the beginning of European colonization. At first, they offered captives to the newcomers and helped them develop new networks of enslavement, serving as guides, guards, intermediaries, and local providers. But with the passage of time, as Indians acquired European weapons and horses, they increased their power and came to control an even larger share of the traffic in slaves. (172)

Tribes engaged in this practice, often, to remove neighboring rivals and acquire their lands but an important aspect of this self-empowerment was the acquisition of the horses and especially the weapons Resendez references. European firearms gave one tribe the upper hand in conflicts with others lacking the same firepower. Recognizing this, colonists armed the natives and enlisted their help further in enslaving others. Scholar Alan Taylor comments, "Drawn into the slave trade by degrees, the natives could not know, until too late, that it would virtually destroy them all" (228). The Narragansett tribe, which had not only helped the English defeat the Pequot but then also took many as slaves, would learn this lesson fully through the conflict known as King Philip's War.

King Philip’s War & Mass Enslavement

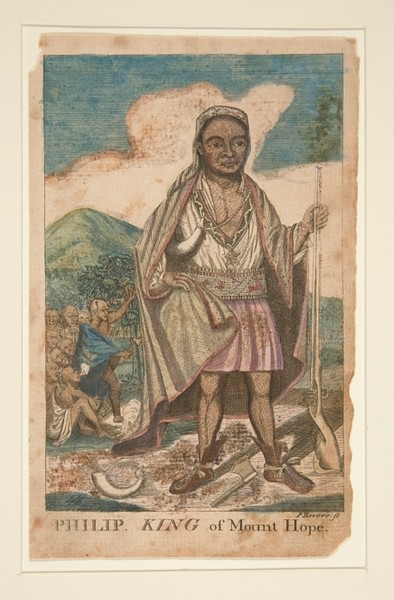

King Philip's War (also known as Metacom's War, 1675-1678) was a large-scale conflict between Native American tribes allied with the chief of the Wampanoag Confederacy Metacom (also known as King Philip, l. 1638-1676) and the colonists of New England. Metacom was the son of Massasoit (l. c. 1581-1661) who had helped the pilgrims of the Plymouth Colony survive and establish themselves. Massasoit had signed the Pilgrim-Wampanoag Peace Treaty with the first governor of Plymouth, John Carver (l. 1584-1621) in 1621, and this treaty was honored until after Massasoit’s death. At this time, Josiah Winslow (l. c. 1628-1680), assistant governor and then governor of Plymouth, initiated policies depriving the Wampanoag of more and more land until Metacom finally took a stand to protect his people and their way of life.

King Philip's War devastated the New England Colonies for over a year until he was betrayed and killed by one of his own people in August 1676, but before that, the Narragansetts – who had remained neutral during the war – were attacked, many killed, and others sold into slavery after the Great Swamp Fight of December 1675. Although the Narragansetts maintained neutrality, they agreed to take in the wounded, women and children, and other non-combatants. To Josiah Winslow, they had forfeited their neutral status by doing so, and he led the attack on their stronghold which killed over 600 Narragansetts, mostly women and children, as well as those of other tribes who had been given refuge.

Afterwards, the surviving members of the Narragansett tribe allied with Metacom against the colonists, but it was too late. Once Metacom was killed, even though some tribes fought on until 1678, the war was effectively over, and both combatants and non-combatants were sold into slavery. One of the reasons these tribes continued the fight, in fact, was the near certainty of being taken and sold into slavery overseas. Scholar Linford D. Fisher elaborates:

Fear of enslavement and, more specifically, the fear of being sold as a slave out of the country played a major role in the waging of King Philip's War…The terrifying prospect of being sent overseas as a slave was constantly present for natives, even in times of peace. The fear of being "Barbadosed" – forcibly and unjustly sent to Barbados as a servant/slave – one could argue, was something applied equally to Indians as well as prisoners of war and criminals in the British Isles. And such fears were not unfounded. New England colonial records routinely and very matter-of-factly report large and small shipments of Indians being sent to Barbados, Bermuda, and Jamaica or, more generically "out of the country". (Why shall we have peace, 1)

Many natives, however, surrendered – even before Philip was killed – in the hopes of leniency and that they would be spared enslavement. Their hopes were largely in vain because Winslow declared all natives complicit in Philip's uprising and so many who had remained completely neutral during the war were shipped out of the country as slaves along with combatants.

These people were not sent to Barbados, however, due to the 14 June 1676 act passed by the Assembly of Barbados prohibiting the import of natives from New England. Barbados, which had a large slave population, had only just thwarted an attempted large-scale uprising by their African slaves in May 1675 and did not want any people imported as slaves who had already participated in an armed revolt elsewhere. The enslaved New England natives were sent to Jamaica, Bermuda, and other English colonies or were shipped down south to work in the tobacco fields of Virginia.

The Westos & Other Slavers

As the English colonies expanded, so did the Native American slave trade, facilitated, in large part, by Native American tribes. Carolina (later North and South Carolina) was founded in 1663, but settlers in that region were already engaged in the enslavement of Native Americans through the actions of the Westo tribe who helped to enslave thousands who were then shipped out of the country. Resendez comments:

In the period between 1670 and 1720, Carolinians exported more Indians out of Charleston, South Carolina, than they imported Africans into it. As this traffic developed, the colonists increasingly procured their indigenous captives from the Westo Indians, an extraordinarily expansive group that conducted raids all over the region. Anthropologist Robbie Ethridge has coined the term "militaristic slaving societies" to refer to groups like the Westos that became major suppliers of Native captives to Europeans and other Indians. (172)

The Westos operated entirely from financial self-interest and were the enemies of all the surrounding tribes. Thought to have originally lived in the north around present-day Lake Erie, they migrated south and first enter the historical record in July of 1661 when they destroyed a Spanish mission in modern-day Georgia. They established themselves in the wilds of Virginia and quickly monopolized the slave trade, raiding other tribes' lands indiscriminately and selling the captives to the colonists. The Westo monopoly continued until the Shawnee brokered a deal with the colonists in trade and allied with them to destroy the Westos completely in 1680. Surviving members of the Westo tribe were then enslaved themselves or escaped, and their fate is unknown. It is unlikely that any would have been taken in by other tribes except as slaves.

The departure of the Westos from the slave trade did nothing to slow or stop it, as the Shawnee then enslaved others they took in raids. Further west, the Spanish had enslaved the native tribes collectively referred to as the Pueblo Indians and were assisted in this by one tribe capturing and selling members of another. In modern-day New Mexico, this continued until 1680 when a Native American leader named Po'Pay organized a mass uprising, known as the Pueblo Revolt, that drove the Spanish from the region for the next decade.

This revolt was primarily motivated by religion in that the Spanish Catholic missionaries suppressed Native American spiritual traditions and replaced them with Catholic Christianity. One of Po'Pay's first acts in the insurrection, in fact, was the declaration that Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary were dead, and missions and churches throughout the region were burned. The Pueblo Revolt exemplifies another aspect of and justification for Native American enslavement by European colonists in that it was their belief that the natives had to be "civilized", and this concept was synonymous with "Christianized". By enslaving natives, the colonists removed them from their traditional spiritual landscape, forcing them to turn toward Christian masters and the Bible for salvation.

The so-called Indian Wars of the 18th century led to further enslavement of combatants and non-combatants beginning with the Tuscarora War (1711-1715) in North Carolina and the Yamasee War (1715-1717) in South Carolina. These conflicts continued up through the eve of the American Revolution and resulted in, among other things, more and more natives shipped out of the country as slaves.

Native American tribes continued to participate in the enslavement of fellow indigenous peoples throughout this time. Many seem to have done so in the belief that, by their participation, they protected themselves from enslavement. By proving themselves useful to the colonists, they thought, they would receive better treatment than others, retain their land, and live as they had before the arrival of the Europeans. As Taylor notes above, they understood too late that they could not trust the words of the white people and that any tribe could be enslaved or removed from their lands for any reason, no matter how hard they tried to ingratiate themselves with the newcomers.

Conclusion

The "civilization" and Christianization of the natives continued throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, but overt enslavement of Native Americans ended around 1750 as Africans became the more popular "commodity" of the slave trade. The first Africans arrived at Jamestown in 1619, and by the 1660s racialized chattel slavery was fully institutionalized in the colonies. Even after slavery was officially abolished in 1865, however, Native Americans continued to be enslaved in North America under the guise of this effort to "civilize" them.

The Dawes Act of 1887 deprived natives of their traditional lands and forced each tribe to prove its "Indian-ness" to be eligible for its return. Natives had no right to vote and, after the Dawes Act, no right to the lands which they had lived on for thousands of years. In addition to having to prove they were legitimate "American Indians", tribes were forced to recognize the European definition of property rights, which were completely alien to the indigenous peoples. Deprived of land, identity, and civil rights, natives who were not already restricted to reservations worked, essentially, as slaves for poor wages or just room and board.

This situation continued until 1900 when white people began recognizing the injustice of colonialism and started to criticize it. Native American authors were finally given a voice and platform and made clear that their culture was equal in civilization to that of any European nation. Native Americans were only granted United States citizenship in 1924, but since then they have steadily fought to reclaim their tribal identities, lands, and dignity as the original inhabitants of North America. Their efforts have been challenged every step of the way by the United States government, which promotes itself as a champion of liberty while still denying the legitimate claims of the indigenous peoples it once enslaved.