The Native American understanding of the land as a living thing, providing for, guiding, and speaking to the people, is expressed in many of their stories, legends, and lore and, among these, in the Sioux legend of The Mysterious Butte in which a butte becomes the prophet of the people.

To the Sioux and other Native American nations, Mother Earth was a sentient being who needed to be respected as one would one's own mother. Just as one would not purposefully harm one's mother, so one should not harm the Earth. In maintaining this relationship of respect and honor with the environment, Native Americans became attuned to its messages – just as one does in a relationship with one's close friends and family – and would recognize when they were being told something, even if it was not always clear what the message meant.

The meaning of some of the Earth's messages was clear enough, but, in many cases, a message would need to be interpreted by a holy man of powerful 'medicine' – spiritual power – popularly known as a 'medicine man.' In the story of The Mysterious Butte, however, the Sioux, after struggling with doubt, come to recognize the spiritual power of the place, and its prophecies are validated through the experiences that follow their encounters with it.

Native American Concept of Land

Historians and anthropologists have often written on how Native Americans considered the land 'sacred' – which is certainly true – but this definition can idealize Native American interactions with their environment owing to the common understanding of 'sacred' and how 'sacred things' are thought to be treated. A better understanding of the Native American concept of the land can be grasped by using the word 'living' – the Earth is alive, like any living thing upon it – and communicates, feels pain, experiences joy, and should be embraced with gratitude like any loved one. Scholar Larry J. Zimmerman writes:

In the myths and ritual that continue to tell of its sacred past, the Earth lives on as the ultimate cosmic gift. It is this intimate relationship that has led to Indians being stereotyped as close to nature. "Noble savages" was the description once used, but in more recent years Native Americans have been labelled the "first ecologists." Protecting the land is part of daily life and many see it as a limitless responsibility. In fact, Indians are ecological in the truest sense – that is, they know nature's cycles and understand its tolerances. They see themselves as a part of the land itself, no better than the other creatures that live on it. To Native Americans, ecology is a matter of balance and respect. (107)

When the European immigrants arrived in North America, a central problem that arose between them and the native population was the different understanding of land rights. To the Europeans, land was to be dominated, tamed, could be bought, sold, and owned; the Native Americans had no such concept of the land. To them, the land was a gift which they had done nothing to deserve and was not in their power to sell. When Native Americans 'sold' land to Europeans, they understood the transaction as they had previously with other tribal nations – as leasing use of the land for a specific purpose, and not selling the land because land could not be owned and so could not be sold.

Further, in the European view, one could farm or hunt one area of land as well as any other, while in the Native American view, the land they had lived on for thousands of years held the story of their past and empowered their present. Rituals and observances drew their spiritual power from the place in which they had been performed by generation upon generation of ancestors and so, in this sense, the land was 'sacred' but, always, it was alive with the history of the people, which each new generation came to know through the stories told of those who had gone before and what the land – that specific land – had taught them and was eager to teach their descendants. This concept is epitomized in the story of The Mysterious Butte.

Text

The following text is taken from Myths and Legends of the Sioux (published 1916) by Marie L. McLaughlin, a one-quarter Sioux who lived on reservations for 40 years and collected the peoples' stories to preserve them. It has been reprinted elsewhere including Voices of the Winds: Native American Legends by Margot Edmonds and Ella Clark.

One time, long ago, when a young man was out hunting, he came to a steep hill. Its east side suddenly dropped off in a precipitous bank. As he stood on that bank he noticed, at the base, a small opening. Examining it closely after going down the slope, he found that the opening was really large enough for a horse or a buffalo to walk through. On each side of this opening he was surprised to see figures of several different animals carved in the wall.

When he entered, he was amazed to see scattered on the floor before him many pipes, bracelets, and other things that people use as ornaments. They seemed to have been offerings to some great spirit.

Passing through this first room, he entered the second and found it so dark that he could not see his hands in front of him. He was frightened. He hurriedly left the place, returned home, and told what he had seen.

The Chief, hearing the young man's story, immediately selected four of his most daring warriors to go with the young man to find out whether or not he was telling the truth. When they reached the place, the young man refused to go inside because on each side of the entrance, the carved figures had been changed!

The four who entered saw that in the first room everything was exactly as the young man had described it. So was their first glimpse of the second room–so dark that they could not see anything. But they continued walking, feeling their way along the walls. At last they found another entrance–or exit. This one was so narrow that they had to squeeze through it sideways. Again they found their way along the walls until they found another opening. This one was so low that they had to crawl on their hands and knees in order to go into the next room.

It was the last one. Entering it, they were surprised by a very sweet odor coming from the opposite direction. Crawling on their hands and knees, and feeling around with their fingers, they found a hole in the ground. Through that hole came the sweet odor. The four warriors hurriedly held a council and decided to return at once to the camp and report what they had learned.

When they reached the first chamber, one young man said, "I am going to take these bracelets to show that we are telling the truth."

"No!" the other three exclaimed promptly. "You are in the abode of some Great Spirit. Some accident may happen to you for taking something that is not yours."

"Aw! You fellows are like old women!" He took a beautiful bracelet and placed it on his left wrist.

When the men reached the village, they reported what they had seen. The one wearing the bracelet shows it, to prove that they had told the truth.

In a short time, these four men were out preparing traps for wolves. As usual, they raised one end of a heavy log and placed a stick under it to hold it up. About five feet from the log, they placed a large piece of meat and covered the space between meat and log with poles and willows. At the spot where they placed the stick, they left a hole large enough to admit the body of a wolf. A wolf would smell the meat and be unable to reach it and because of the poles and willows, the men felt sure, would crowd itself into the hole. Then it would work itself forward in order to get the meat. When its movement pushed down the stick, the log would trap the wolf under its weight.

When the young man wearing the bracelet followed this procedure with a large piece of meat, the log caught the wrist on which he wore the bracelet. Unable to release himself, he called loud and long for help. Hearing his call, his companions hurried to assist him. When they lifted the log, they found that the man's wrist had been broken.

"Now you have been punished," they said. "You have been punished for taking the bracelet out of the chamber of this mysterious butte."

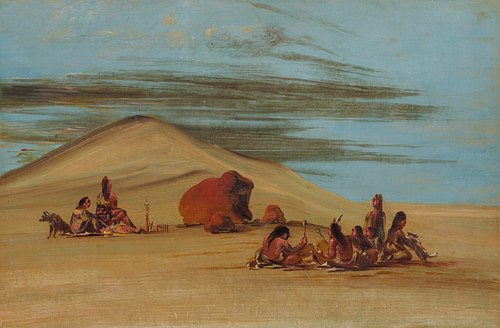

Some time later, a young man who went to the butte saw engraved on the wall the figure of a woman holding a pole in her hand. With it she was holding up a large amount of meat that had been laid across another pole. It had been broken in two from the weight of so much meat. On the wall, on all sides of the figure of the woman, were the footprints of buffalo.

The next day an enormous herd of buffalo came near the village, and a great many were killed. The women were very busy cutting up and drying the meat. More buffalo meat was at one camp than was at any other. When one of the women was hanging meat upon a long tent pole, the pole broke in two. So she had to hold the meat up with another pole, just as in the engraving the young man had seen on that mysterious butte.

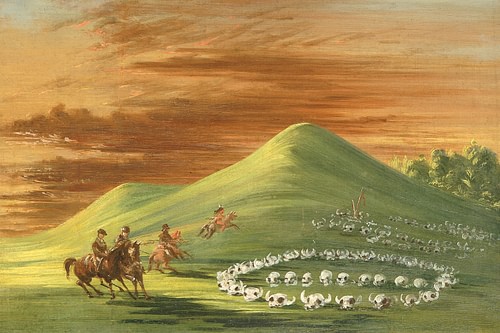

Even after that, the people paid weekly visits to this butte, and would read there the signs that would govern their plans. The butte has been considered the prophet of the band of Sioux who told this story for generations and generations.

Commentary

As with all civilizations around the world, past and present, Native American stories serve to entertain but also to impress upon an audience the peoples' cultural values. An interesting aspect of The Mysterious Butte is how it treats the concepts of faith and unbelief.

The people encounter the butte three times. The first time, the young hunter returns to his village and tells of what he has seen but is doubted. The chief immediately selects four warriors to go back with the young hunter to see if he is telling the truth. When they arrive, and the hunter sees the carved figures have been changed, he refuses to enter, recognizing it is a sacred place. On this second visit to the butte, one of the warriors scoffs at the suggestion that he should leave the bracelet in the chamber because it belongs to a great spirit; he later pays for this when his wrist is broken while setting traps. After this, another young man visits the butte and sees the prophecy of the buffalo, but the story does not say whether he told anyone about it. The next day, the prophecy comes true, however, and, after that, the people consult the butte weekly for direction and guidance.

An audience hearing the story would be encouraged to believe in what Earth was saying to them initially without requiring proof. The story itself serves as proof of the efficacy of faith in that what is predicted – once by the other warriors and then by the engravings – comes to pass. The story is intended to encourage listening to the messages from Earth and believing them without needing further corroboration.

The Mysterious Butte touches on a concept understood by all Native American nations of the 'present past' – the invisible world that exists alongside and within observable reality, the realm of spirits, of one's ancestors, and the voice of the Earth which can only be heard if one believes in the Earth's vitality and sentience. The past is always present in Native American belief, and that past is intimately tied to the land on which those past experiences took place. When the people in the story finally abandon unbelief and accept the reality of the butte's message, only then do they find guidance and balance in that place. When the story would be told to later generations, they would understand the power of that specific place and what it had to tell them.

The story also serves to highlight the difference between the culture of the Native Peoples of North America and that of non-natives, as Zimmerman observes:

The message of much Indian literature is that white people are out of sympathy with the land because they are driven to conquer and dominate it, whereas the Native approach is to listen to what the land has to say and discover a way of living in harmony with it. In a disorienting world, such literature aims to make people whole again by reference to ancient patterns of order and meaning that are enshrined in the oral tradition of storytelling. (265)

In the case of The Mysterious Butte, one message an audience might take away would be "Don't be like the white man who cannot hear what Mother Earth is saying." By emphasizing the importance of faith in what the Earth has to say and listening for its messages, the story highlights the value of the intended audience's traditional values.

Conclusion

These values, as Zimmerman notes above, include caring for the Earth as one would one's own mother. Native Americans certainly can be defined as the 'first ecologists,' but it is not as though they were so in the past but are no longer. Native American activists continue to advocate for the protection of the environment and emphasize the importance of balanced living and respect for nature. Zimmerman writes:

Indians [historically] have had to pay careful attention to the land's ability to sustain them [and maintain balance between human needs and those of nature] …This harmony between humans and nature was changed by the settlement of Europeans in North America. By the late 1800's, the buffalo was nearly extinct. Tribal lands have since been cleared of forests and waters have been polluted. Many Indians have stepped forward to speak out against this desecration and have become eloquent spokespeople for a range of contemporary environmental causes. (107)

The balance between the needs of the people and those of the environment is another central theme of The Mysterious Butte in the section on the warrior stealing the bracelet from the butte's chamber. In failing to respect and honor what belongs to the natural/spiritual world, the warrior brings his punishment on himself through the broken wrist while, by observing and listening to what nature has to say – even though he tells no one – the young man at the end is rewarded by seeing his vision become a reality. In the present day, Native American storytellers relate the tale of The Mysterious Butte in the hope that modern audiences recognize the message of the story as just as vital and important now, if not more so, as it was when first told