Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 605/604-562 BCE) was the greatest King of ancient Babylon during the period of the Neo-Babylonian Empire (626-539 BCE), succeeding its founder, his father, Nabopolassar (r. 626-605 BCE). He is best known from the biblical books of Daniel and Jeremiah where he is portrayed as the king who stands against God.

Nabopolassar had defeated the Assyrians with the help of the Medes and liberated Babylonia from Assyrian rule. He then continued his conquest of the region and so provided for his son a stable base and ample wealth on which to build; an opportunity for greatness which Nebuchadnezzar took full advantage of in the same way that Alexander the Great (r. 336-323 BCE) would later capitalize on the treasury and standing army left him by his father Philip II of Macedon (r. 359-336 BCE).

Nebuchadnezzar married Amytis of Media (l. 630-565 BCE) and so secured an alliance between the Medes and the Babylonians (Amytis being the daughter or perhaps granddaughter of Cyaxares, King of the Medes) and, according to some sources, had the Hanging Gardens of Babylon built for her to remind her of her homeland in Persia.

Upon ascending to the throne, Nebuchadnezzar spoke to the gods in his inaugural address:

O merciful Marduk, may the house that I have built endure forever, may I be satiated with its splendor, attain old age therein, with abundant offspring, and receive therein tribute of the kings of all regions, from all mankind. (Kerrigan, 39)

It would seem that his patron god Marduk heard his prayer in that, under his reign, Babylon became the most powerful city-state in the region and Nebuchadnezzar II himself the greatest warrior-king and ruler in the known world.

He is portrayed in unflattering light in the Bible, most notably in the Book of Daniel and the Book of Jeremiah where he is seen as an 'enemy of God' and one whom the deity of the Israelites intends to make an example of or, conversely, the agent of God used as a scourge against the faithless followers of Yahweh. He died in the 43rd year of his reign as the most powerful monarch in the Near East in the city he loved.

Early Life & Rise to Power

Nebuchadnezzar II was born in c. 634 BCE in the region of Chaldea, in the southeast of Babylonia. His name is actually Nabu-kudurru-usur (“Nabu, Preserve My First-Born Son”) in Chaldean while 'Nebuchadnezzar' is the name by which the Israelites of Canaan knew him (from the Akkadian 'Nebuchadrezzar'). He was the eldest son of a Babylonian general in the Assyrian army, Nabu-apla-usur (“Nabu, Protect My Son”), better known as Nabopolassar.

At this time, the Assyrian Empire still controlled the region but was in its final days. The empire had grown too large to maintain and began to weaken toward the end of the reign of the last great Assyrian king Ashurbanipal (r. 668-627 BCE). In 627 BCE, the Assyrians sent two of their representatives to take charge of Babylon but Nabopolassar refused to support them, sent them back home, and was crowned king in 626 BCE.

For the next ten years Nabopolassar fought the Assyrians while Nebuchadnezzar grew up, receiving an education in military matters as well as general literacy and government administration. In 615 BCE, Nabopolassar attacked the city of Ashur but was unable to take it until the Medes under their king Cyaxares joined the resistance and Ashur fell. Nabopolassar then entered into an alliance with Cyaxares and confirmed it with the marriage of Nebuchadnezzar to Cyaxares' daughter (or granddaughter) Amytis.

In 612 BCE, the city of Nineveh fell to the Babylonian-Mede coalition and this date is recognized as the end of the Assyrian Empire. Even so, the last Assyrian king, Ashur-uballit, struggled to regain power with the help of the Egyptians under pharaoh Necho II (r. 610-595 BCE). Necho II was defeated in battle by Nebuchadnezzar II in 605 BCE near Carchemish and sometime shortly after this Nabopolassar died, of natural causes, in Babylon. Nebuchadnezzar returned to the city a war hero and was crowned king in either late 605 or early 604 BCE.

Consolidation & Restoration of Babylon

Nabopolassar had formed his empire through conquest by 616 BCE and Nebuchadnezzar II drew on these resources to strengthen and enlarge his armed forces as well as engage in building projects. He absorbed all of the former regions of the Assyrian Empire and crushed whatever resistance was offered. In 598/597 BCE he marched on the Kingdom of Judah in Canaan and lay siege to its capital city of Jerusalem, sending the elite citizens of the city back to Babylon, a period known as the Babylonian Captivity.

Further resistance by Judah resulted in another round of military campaigns between 589-582 BCE (including the destruction of Jerusalem in 587/586 BCE) which reduced the kingdom and scattered the populace. After the Canaanite city of Tyre finally fell to a lengthy siege in 585 BCE, Nebuchadnezzar II had consolidated his empire.

He then engaged in monumental building projects which renovated and refurbished thirteen of his cities completely but he put the greatest effort into the most famous: Babylon. Scholar Susan Wise Bauer comments:

He had his own position as great king to establish and maintain and he set out to do this as Mesopotamian kings had done for two thousand years: he started to build. His own inscriptions record the restoration and addition of temple after temple in Babylon itself. Babylon was the home of the god Marduk and Nebuchadnezzar's devotion to Marduk was also a celebration of Babylonian triumph. (447)

An important part of his restoration project was rebuilding the great ziggurat known as Etemenanki ("the foundation of heaven and earth") which had been destroyed by the Assyrian king Sennacherib (r. 705-681 BCE) along with the rest of Babylon. Rebuilding began under Sennacherib's son, Esarhaddon (r. 681-669 BCE), under Nabopolassar, and was completed by Nebuchadnezzar II. The Etemenanki, with its great rising tower, is thought to be the inspiration for the biblical Tower of Babel.

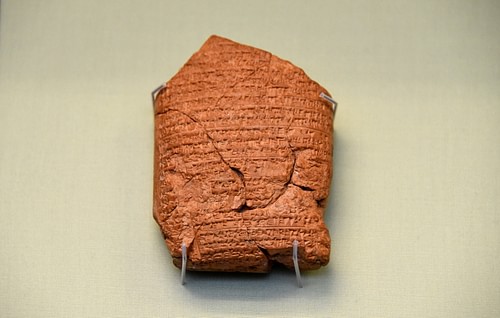

By 600 BCE, Babylon was so impressive it was considered the center of the world; certainly by the Babylonians themselves and, seemingly, by others. A clay tablet dating to this time, discovered in the ruins of the city of Sippar (north of Babylon) and presently in the British Museum, presents the ancient world revolving around Babylon. The tablet purports to be a map of the world but actually marginalizes most of the regions surrounding Babylon, including Sippar. The map's origin is Babylonian and how it arrived in Sippar is unknown but it is possible this piece is one of many held by cities who honored Nebuchadnezzar II's reign and his great urban center. Scholar Michael Kerrigan notes:

In presenting a view of the world, any map at the same time presents a 'worldview' – an ordered set of assumptions and attitudes. This one, with its breezy metro-centrism, its apparently unquestioning assumption that Babylon was the hub at the heart of things, speaks volumes for the self-confidence of the city. (36)

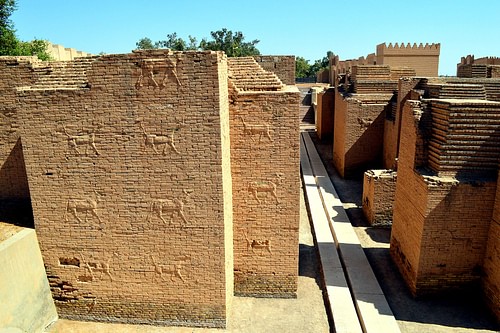

The great temples and monuments were accented and made accessible by new roads and special attention was given to the creation of the Processional Way for the Festival of Marduk during which the god's statue was taken from the temple and paraded through the city and out beyond the gates. This road was 70 feet (21 m) wide and ran from the temple complex in the heart of the city out through the Ishtar Gate in the north, a considerable distance of over half a mile (nearly a kilometer) in length with walls rising over fifty feet (15.2 m) on either side. These were decorated with over 120 images of lions, dragons, bulls, and flowers in gold.

...of bricks with blue stone on which wonderful bulls and dragons were depicted. I covered their roofs by laying majestic cedars length-wise over them. I hung doors of cedar adorned with bronze at all the gate openings. I placed wild bulls and ferocious dragons in the gateways and thus adorned them with luxurious splendor that people might gaze on them in wonder. (Kerrigan, 39)

The walls of Babylon and the Ishtar Gate were considered so impressive that some ancient writers claimed they should have been included on the list of the Seven Wonders. Babylon was included on that list but for a different attraction: the Hanging Gardens.

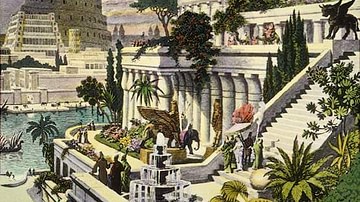

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon

The Hanging Gardens are the only one of the ancient Seven Wonders whose existence is disputed because no archaeological evidence has been found of them and, further, the only known reports of them come from after Babylon's fall. Even more significantly, the famous East India House Inscription - a paean of praise written by Nebuchadnezzar II himself boasting of his beautification of the city (and so called because it was discovered by a representative of the East India Company in 1801) - makes no mention of the Hanging Gardens. They are most explicitly described in a passage from Diodorus Siculus (l. 90-30 BCE) in his work Bibliotheca Historica, Book II.10:

There was also, because the acropolis, the Hanging Garden, as it is called, which was built, not by Semiramis, but by a later Syrian king to please one of his concubines; for she, they say, being a Persian by race and longing for the meadows of her mountains, asked the king to imitate, through the artifice of a planted garden, the distinctive landscape of Persia. The park extended four plethra on each side, and since the approach to the garden sloped like a hillside and the several parts of the structure rose from one another tier on tier, the appearance of the whole resembled that of a theatre. When the ascending terraces had been built, there had been constructed beneath them galleries which carried the entire weight of the planted garden and rose little by little one above the other along the approach; and the uppermost gallery, which was fifty cubits high, bore the highest surface of the park, which was made level with the circuit wall of the battlements of the city. Furthermore, the walls, which had been constructed at great expense, were twenty-two feet thick, while the passage-way between each two walls was ten feet wide. The roofs of the galleries were covered over with beams of stone sixteen feet long, inclusive of the overlap, and four feet wide. The roof above these beams had first a layer of reeds laid in great quantities of bitumen, over this two courses of baked brick bonded by cement, and as a third layer a covering of lead, to the end that the moisture from the soil might not penetrate beneath. On all this again earth had been piled to a depth sufficient for the roots of the largest trees; and the ground, which was levelled off, was thickly planted with trees of every kind that, by their great size or any other charm, could give pleasure to beholder. And since the galleries, each projecting beyond another, all received the light, they contained many royal lodgings of every description; and there was one gallery which contained openings leading from the topmost surface and machines for supplying the garden with water, the machines raising the water in great abundance from the river, although no one outside could see it being done. Now this park, as I have said, was a later construction.

Diodorus refers to “a Syrian king” following the Greek tradition of referring to Mesopotamia as Assyria but it may also be because he was describing gardens in the Assyrian city of Nineveh instead of at Babylon. Sennacherib had famously made Nineveh the jewel of the Assyrian Empire just as Nebuchadnezzar II would later do at Babylon. It has been established that Nineveh boasted many magnificent parks and gardens and based on this, and on the distance in time between Nebuchadnezzar II's reign and reports of the Hanging Gardens, scholars now believe they were located at Nineveh if they existed at all.

Diodorus' description of the gardens appears in his book in the section on the semi-mythical Assyrian queen Semiramis and it is possible he was conflating a story concerning her, of which there were many, with a later story concerning Nebuchadnezzar II and Amytis. No clear answer is forthcoming to this question, however, and most scholars still adhere to the traditional view that Diodorus and the other historians were reporting various versions of an actual historical site at Babylon. Nebuchadnezzar II is said to have created the gardens for his wife who missed the landscape of her homeland and this detail is included in Diodorus' description.

Even though no physical evidence of the Hanging Gardens has been found at Babylon, there is no reason to believe that Nebuchadnezzar II would not – or could not – have built them there. Scholar Paul Kriwaczek notes:

Nebuchadnezzar marked the city's regained status by raising it to its greatest prominence ever. He made it the largest, the most splendid, and in some eyes the most glamorous city the world had ever seen. (262)

Although there is no doubt this is true – almost every ancient writer addresses Babylon with a tone of awe and reverence – it was not an opinion shared by all and, unfortunately for Babylon's reputation, those who did not would become the most widely-read source on the city: the Hebrew scribes responsible for the narratives of the Bible.

Nebuchadnezzar in the Bible

Nebuchadnezzar II had orchestrated the so-called Babylonian Exile (Babylonian Captivity) of the Jews following the destruction of the Kingdom of Judah, so, unsurprisingly, the Hebrew scribes had no love for him or his city. The Jews of the 6th century BCE, like many ancient peoples, believed that their god resided in the temple dedicated to him. When Nebuchadnezzar II destroyed the temple in Jerusalem, he literally destroyed the house of god.

Judaism – again, like other religious belief systems – was based on an understanding of quid pro quo (this for that) in which the people paid homage to their god and that god provided for and protected the people. When the temple was destroyed – and then the rest of the kingdom – and the people carried off to a foreign land, some explanation had to be found by the priestly class to explain it.

The conclusion reached by the Jewish clergy was that, previously, they had been led astray by other gods and beliefs and had not paid enough attention to the sole worship of Yahweh. In the era known as the Second Temple Period (c. 515 BCE-70 CE), Judaism was revised in light of the Babylonian Captivity to focus on monotheistic belief and practice and, at the same time, the narratives which would become their scriptures were edited to fit this new focus.

Babylon and Nebuchadnezzar II – described in the most glowing terms and phrases in other works from the ancient world – accordingly receive poor treatment in the Bible. Babylon is routinely characterized as a city of sin and evil and Nebuchadnezzar II appears in the Book of Daniel as a stubborn tyrant who recognizes the power of Daniel's god but will not submit to him until he is literally driven insane and is then restored. In the Book of II Kings the scribes relate the sack of Jerusalem, and Nebuchadnezzar II is mentioned elsewhere as well, but it is primarily the Book of Daniel which has cemented Nebuchadnezzar's reputation for the largest audience.

In Daniel 1-4, Nebuchadnezzar is witness to the power of Daniel's god when the three Jewish youths Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednago refuse to worship the golden idol the king has created and decreed that all should bow before. He has them thrown into a furnace but they are saved through their faith and emerge unharmed (Daniel 3:12-97). The god of the Israelites also grants Daniel the ability to interpret dreams and he displays this skill for the king in rightly interpreting his vision of the tree (Daniel 4:1-24).

The most dramatic event for Nebuchadnezzar in this account is when a voice comes down from heaven declaring he will shortly go insane and this comes swiftly to pass (Daniel 4:25-30). Nebuchadnezzar is said to have been “driven away from among men, and did eat grass like an ox, and his body was wet with the dew of heaven until hairs grew like the feathers of eagles and his nails like bird's claws.” (4:30). The madness lasts for seven years, just as the voice from heaven predicted, and then the king's sanity is restored and he gives praise to God.

Conclusion

Although the Book of Daniel is a fascinating narrative, there is no outside corroboration for the story of the king's madness nor of any particular stubborn streak. It is not surprising that a people who felt they had been victimized by this king should depict him negatively in their narratives but this does not mean those narratives are historically accurate.

Nebuchadnezzar II in other sources is depicted as a great king who not only restored Babylon to its former glory but transformed it into a city of light. Under his reign, Babylon became a city which was not only wondrous to behold but also a center for the arts and intellectual pursuits. Women enjoyed equal rights under Nebuchadnezzar's rule (though not completely equal in status by any modern-day standard) schools and temples were plentiful, and literacy, mathematics, the sciences, and craftsmanship flourished along with a tolerance of, and interest in, other gods of other faiths and the beliefs of other cultures.

In many ways, the ceramic map depicting Babylon as the center of the world was accurate. Nebuchadnezzar II envisioned a city which people ever after would view in wonder and then made that vision a reality. He died peacefully of natural causes in the city he had built after a reign of 43 years but Babylon would not last even another 25 after his death. The city fell to the Persians in 539 BCE and later efforts to restore it by Alexander the Great never elevated it to the heights it had known under the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II.