The New Model Army was created in February 1645 by the Parliamentarians during the English Civil Wars (1642-1651) that turned England from a monarchy to a republic. It was a professional army in terms of its personnel, training, and leadership and was formed after heavy defeats to the Royalists earlier in the war.

Commanded first by Sir Thomas Fairfax (1612-71) and then Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658) from 1650, the force consisted of around 68,000 men at its peak in the early 1650s. The organisational structure of the Parliamentary army set the model for the professional British army of subsequent centuries.

Civil War

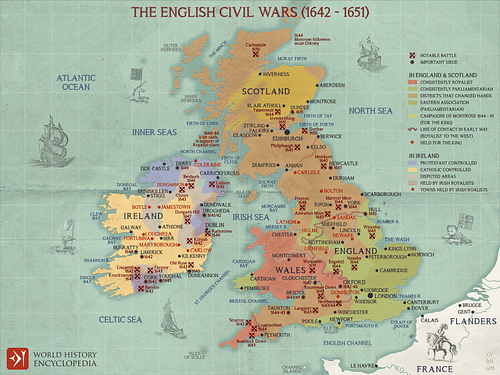

Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649) considered himself an absolute monarch with absolute power and a divine right to rule, but his unwillingness to compromise with Parliament, particularly over money, led to a civil war from 1642 to 1651. Fought between the 'Roundheads' (Parliamentarians) and 'Cavaliers' (Royalists) in over 600 battles and sieges, the war was a bloody and protracted conflict. The northern and western parts of England largely remained loyal to the monarchy, but the southeast, including London, was controlled by Parliament.

Early Failures

Defeat at Roundway Down in July 1643 saw the near-destruction of the Parliamentary army of the Western Association (several southwest counties) led by Sir William Waller (1597-1668). One of the problems for the Parliamentarians was that their best force, the London regiments, were not available for lengthy service since their absence from the capital severely impacted commercial activity. Accordingly, in March 1644, Parliament freed more funds for a permanent army, but it was not enough.

The new force fought at Cropredy Bridge on 28 June and at the Second Battle of Newbury on 27 October 1644. Charles I led his army in person in the former battle and won, the second saw neither side gain the upper hand, despite the Parliamentarians having a numerical advantage of 2:1. These setbacks again led to a Parliamentarian discussion on how to form a permanent and more professional army, a move called for by Oliver Cromwell in December 1644, a country gentleman and a visionary military leader. What was needed was a standing army that could take the field wherever their commanders thought best and for however long it took to gain victory, a significant consideration given that the war involved many lengthy sieges. Another weakness had been the competition between the various Association armies and the absence of any overarching hierarchy of command.

On 4 February 1645, Parliament sanctioned the formation of a professional fighting force: the New Model Army. The costs were met from highly unpopular taxes and excise duties. Although the majority of soldiers were volunteers from various existing armies, the target of 14,400 troops proved unrealistic and necessitated the impressment of several thousand infantry. With these inherent weaknesses, the Parliamentarians had devised a way to win the war, but not how to keep lasting control of their new republic.

Command Structure & Organization

A significant development in England's army was Parliament's decision, effective from April 1645, to forbid any of its members from also being a military commander. The effect of the Self-Denying Ordinance was to remove any commanders who were politically powerful but had no military competence. Not only were the troops now professionals but also the senior officers. Sir William Waller was amongst the casualties of those who had to give up their commands. The first overall commander of the New Model Army was Sir Thomas Fairfax, a man of talent and experience.

The Model Army was initially composed of 11 cavalry regiments, 12 infantry regiments, one dragoons regiment (hybrid cavalry-infantry), and two companies of 'firelocks' (artillery and musketeers). Each regiment bore the name of its commanding colonel. There were also some Parliamentary armies not initially absorbed into the Model Army. The 24 regiments grew to eventually number nearly 100, depending on circumstances. The enlarged army was thus broken down into 62 infantry, 28 cavalry, 4 dragoon, and a number of artillery regiments. At its peak, the Model Army boasted some 68,000 men.

The Commander-in-Chief was assisted by the Lieutenant-General of the Horse, the Sergeant-Major-General of the Foot, and the Lieutenant-General of the Ordnance, who commanded respectively the cavalry, infantry, and artillery regiments. There was the Commissary-General of Victuals, who looked after food supplies, and various other lower levels of staff officers who helped orchestrate the regiments and the logistics required to keep them active in the field.

Each infantry regiment, at full strength, was composed of around 1,200 men organized into ten companies of various sizes depending on the seniority of the officer commanding them. However, regiments were rarely at full strength, and a force of 500-700 men was typical. Companies could be joined to create divisions, a rather loose classification that depended on the tactical necessities of the engagement.

Below the regiment's commanding colonel was a lieutenant-colonel, sergeant-major, and the company captains. Each captain had a lieutenant and several sergeants who were responsible for keeping good order and ensuring everyone had a ready supply of powder and ammunition. The lowest rank was a corporal who looked after a number of privates, particularly when they first joined. For each company, there was an ensign to carry the regiment's colours and two drummers who dictated to the troops what positions they must take, when to advance, retreat, and so on. Flags were also used in battle to organise troop movements.

The dragoons regiment consisted of around 1,000 mounted infantry, that is, they dismounted for battle, at least in the early part of the war. Eventually, they became regular cavalry. The horse regiments were each organised into 6-8 units of 60-80 riders. The colonel (or the lieutenant-colonel), sergeant-major, and captains each led a unit which eventually became standardised to number six units of 100 riders. The diversity in cavalry composition was reflected in such special units as Cromwell's own cavalry force, known as 'The Ironsides', which had 14 units.

Artillery was vital in 17th-century warfare. The Model Army began with 56 cannons, but the force expanded over time, especially with additions captured from the enemy. The artillery and its operators were protected by two companies of musketeers with the latest flintlock weapons to avoid using the older slow-burning matches that could set off the nearby gunpowder.

Pay & Rations

The majority of the army were volunteers and fought from political and religious convictions that the king was a wicked ruler. It was believed that God would punish Charles and use the Model Army as his tool. Troops were issued with Bibles and printed catechisms to carry on their person which outlined the cause they were fighting for. All regiments had chaplains, and there were regular sermons and prayer meetings. Just how much this religious fervour was imposed from the top down or rose from the grassroots is open to debate.

Whatever their personal reasons for fighting, all soldiers were paid, but salaries varied during the war. At the beginning, an infantryman received 8d a day while a dragoon got 1 shilling 6d, and a cavalry rider 2 shillings. Gentlemen officers received higher salaries, but they lived off their own private means anyway, and they could claim certain additional expenses such as maintaining horses. At the top, a colonel could expect 20 shillings a day. These figures fluctuated to match inflation with reductions if the soldier was merely in camp and not in battle. Deductions were also made for clothing issued and for food when the army was on the march (when not, soldiers were hosted by private households who, in theory, were compensated for the cost). Little wonder that ordinary soldiers plundered what they could, an action officially prohibited but difficult to control and even permitted by some commanders for a brief period after a battle. High-ranking officers and commanders, on the other hand, could expect rewards for victories, which ranged from jewellery to landed estates. A new innovation after 1650 was to reward middle-rank soldiers with victory medals, the first carried a likeness of Cromwell.

Feeding a large army in the field was an age-old problem. Local areas were sucked dry of supplies and given tickets to be later repaid by Parliament (a slow and not usually successful process). Most soldiers were glad to get their 450 g (1lb) of bread and half that of cheese daily ration, but this was rarely the reality. One source that was out of bounds was the regiment's supply dump since anyone caught pilfering was severely whipped. Foraging, hunting, and poaching were often the only ways to supplement the meagre diet, but a soldier had to be careful he was not accused of deserting, since the punishment was execution. Clearly, discipline in the Model Army was a factor as important as professional training in making it a highly effective fighting machine.

Uniform & Armour

Model infantry wore Venetian red coats, although there were regimental variations. The most common outer garment was the 'cassock', a long coat with long sleeves and buttons. Grey or dull-cloured baggy breeches were worn tied at the knee. A double layer of stockings was worn and leather shoes. Pikemen generally wore metal helmets, particularly the morion - a round helmet with a reinforcing central spine, wide brim, and cheek plates. Body armour took the form of metal breast- and backplates attached with leather straps, but it became a rarer sight as the war developed.

Model cavalry wore a 'buff coat' - a long- or short-sleeved thick jacket that billowed out below the waist and which provided some protection to sword slashes. Over this, they might wear a long leather coat. For ease of movement, cavalry wore less baggy trousers than the infantry and leather riding boots that went above the knee (but which could be folded down). A common type of helmet was the zischagge or 'lobster-tail pot' which had a round crown, neck- and cheek-guards, and a front peak. The nickname derives from the overlapping metal strips of the neck-guard resembling a lobster tail. Breast- and backplates might be worn, and armour for the arm which held the horse's reins.

Musketeers wore a high, wide-brimmed felt hat which was typically given a personal touch by adding feathers. As the war drew on, many pikemen swapped their helmet for this type of hat. A third type of headgear was a sort of knitted skullcap with tassel, the Monmouth cap.

The name 'Roundheads' for the Parliamentarians derives from their Puritan members wearing their hair very short, but this only pertained to the early period of the war, in reality, many officers on both sides wore long wigs and extravagant clothing. It was, consequently, not so straightforward to distinguish between the two sides in terms of dress, and for this reason, coloured sashes, ribbons, and even sprigs of foliage were worn as 'field signs'. Additionally, the coloured lining of one's coat was exposed by folding back the cuffs. Unfortunately, field signs did not prevent incidents where officers found themselves leading away a group of the enemy instead of their own men.

Weapons

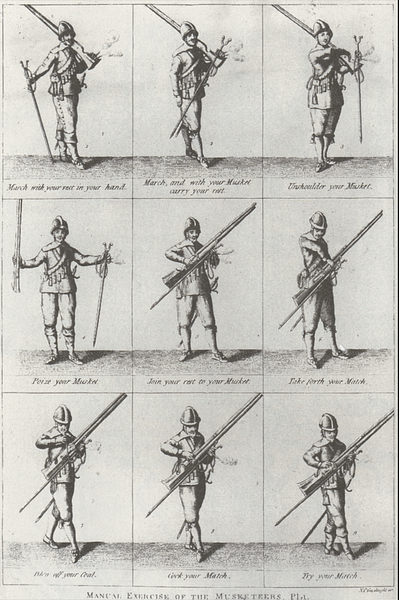

Infantry were armed with pikes (one-third) or muskets (two-thirds). In battle, the infantry companies were arranged into six rows of men with the musketeers on the flanks. The most experienced fighting men were placed at the front. The tightly formed units bristled with 5.5 metres (18 ft) pikes, ash poles with a steel spike.

Musketeers used the matchlock musket, a firearm with a barrel up to 122 cm (48 in) in length. The weapon was heavy and had to be supported with a V-topped pole, although this became unnecessary with new lighter designs later in the war. A musket ball was quite heavy (28 g / 1 oz) and could easily smash through bone. Not particularly accurate, if a target was further than 90 metres (100 yards) away, the shooter was firing more in hope. For this reason, muskets were most effective as volley fire. Firing them was a slow business. Powder, bullet, and wadding were rammed down the barrel. The priming powder was poured into the lock mechanism, and the match was lit, which set off the powder with a cloud of smoke and fired the bullet. Consequently, musketeers fired in ranks and then moved to the rear to reload.

Musketeers had to carry quite a bit of equipment: the 'Twelve Apostles' (12 prepared cartridges), a powder flask, a priming flask, a pouch of bullets, and spare matches. This equipment had to be kept dry so battles in wet weather greatly reduced the effectiveness of musketeers. The flintlock rifle was more expensive, but its advantages meant it eventually came to outnumber matchlocks. The flintlock did not need a lit match but lit the powder by creating a spark when the trigger caused a lever to strike against flint in the breech. Some riders had pistols, even more expensive than flintlocks and not a great deal lighter with up to 60 cm (24 in) barrels.

Swords were worn by most infantry and horsemen, but only by some musketeers and pikemen. The style was up to the individual, gentlemen preferring a thin rapier-like blade with an ornate 'basket' guard. Cavalry tended to wield more durable broad swords with a double cutting edge.

Cannons were used in sieges and open battles. Coming in all sizes, they required three men to operate and at least six horses to move around. Siege cannons of the period could fire a solid ball of stone, lead, or iron up to 27 kg (60 lb) in weight. There were also shells - hollow metal balls filled with powder and set with a short fuse. Field cannons were smaller, the largest of this type being the culverin, which typically fired balls up to 9 kg (20 lb) in weight. Cannons were set on carriages and positioned within earthworks for protection. The effective range of most cannons was around 730 metres (800 yards), but they could fire an impressive 10 to 15 times per hour, which, multiplied by the number of cannons in a battery, allowed for a continuous and harrowing bombardment of the enemy.

Victories

The Model Army proved its worth in June 1645 at the battle of Naseby, Northamptonshire. The Royalists, numerically inferior, were destroyed by the well-trained and well-disciplined Parliamentarian cavalry. The victory was quickly followed by another near Langport in Somerset against a 7,000-strong Royalist force. Next came a test of the army's siege capabilities. Bristol, then in the hands of Prince Rupert (King Charles' nephew), was, with its port, a vital stronghold. The Model Army surrounded the city, took a number of its defensive fortifications, and succeeded in gaining a surrender from Rupert. The Royalists had never suffered such a blow. In March 1646, at the Battle of Stow-on-the-Wold, a Royalist army was again defeated. The Model Army had brought victory in the war, or as it turned out, what has become known as the First English Civil War (1642-1646).

In the Second English Civil War (Feb-Aug 1648) a Scottish army invaded England to rescue Charles from his hideaway on the Isle of Wight. Simultaneously, royalists rose again in various isolated pockets, notably in Kent and Essex. Once again, the Model Army proved superior, both in the south under Fairfax and in the north of England under Cromwell, against the combined Scots and English rebels at the battle of Preston in 1648.

Political Influence & Disbandment

The Model Army was now so powerful it could even challenge Parliament and ignore its decision to disband it. Marching on that institution in December 1648, the army sought to apprehend Presbyterian members of the Parliament and press for arrears in their pay to be met. By now, the army command was dominated by the Independents, and they saw the Presbyterians not as allies against the monarchy but serious rivals to their ambitions to promote their brand of the Christian faith. Another group seeking to infiltrate the army high command was the Levellers, radicals who wanted to equalize wealth and extend suffrage. In short, the army was becoming a political tool, rather than a military one. Meanwhile, Charles was tried for treason and executed in January 1649. Still, the war was not over. In 1650 there was a major rebellion in Ireland against the regicide, and Cromwell led 12,000 men of the Model Army to put it down with great ruthlessness.

Still not all over, the Scots then supported Charles I's son, another Charles, and so the Model Army was sent north again. Fairfax, concerned at how the war had developed, refused to lead the army, and so Cromwell took over as commander-in-chief. Cromwell led 16,000 men and won an important victory at the battle of Dunbar in 1650 and captured Edinburgh Castle on Christmas Eve. In September 1651, a Scottish invading army was roundly defeated at Worcester by the Model Army, once again led in person by Cromwell. It had been a bitter campaign, but the Civil Wars were finally over.

The Model Army's political power is evidenced in the reduction in size and power of Parliament and, in December 1653, the appointment of its commander Cromwell as the Lord Protector of England. The new Republic was divided into 12 military districts, each led by a major-general. Following Cromwell's death, Parliament voted to restore the monarchy in May 1660. The Republic had been short-lived, but its New Model Army, although largely disbanded by the new monarch Charles II of England (r. 1660-1685), had established the organisational basis for the enduring success of the professional British Army for the next 250 years.