Nikephoros I ruled as emperor of the Byzantine Empire from 802 to 811 CE. A former finance minister who did much to improve the state economy, Nikephoros was not particularly popular with the empire's overtaxed peasants and overregulated merchants. Initially successful in his foreign affairs when he won victories in the Balkans, he then faced a rebellion in Asia Minor in 806 CE and subsequent losses to the Abbasid Caliphate. The emperor was killed on the battlefield fighting in Bulgaria, and his skull was infamously made into a silver-lined drinking cup by his nemesis the Bulgar Khan Krum.

Succession

Irene the Athenian (r. 797-802 CE) had been the first-ever woman to rule as Byzantine emperor in her own right. The wife of Leo IV (r. 775-780 CE) and regent for her young son Constantine VI from 780-790 CE, Irene took sole power in 797 CE after enduring the ignominy of exile following her insistence she should rule above her son no matter what age he reached. However, her proposed marriage alliance with Charlemagne, king of the Franks and Emperor of the Romans in the west, was a step too far for the Byzantine establishment and she was deposed and exiled for the second time in October 802 CE. Nikephoros, the chief finance minister (logothetes tou genikou) under Irene, was selected as the new emperor.

Domestic Policies

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given his former ministerial role, Nikephoros quickly set about putting the Byzantine economy on a sounder footing after the chaotic years of Irene's reign. For some time the state coffers had been less full than they ought to have been because of inefficiencies in tax collection and Irene giving out too many tax privileges to all and sundry. Accordingly, the tax rolls were reassessed and new land taxes imposed. There was a new tax, the hearth tax (kapnikon), which was payable by all peasant tenants who worked on land owned by churches and monasteries. Another burden was the obligation of all villages to finance the military arms and equipment of those community members who could not afford to do so themselves. The village was also expected to pay the tax arrears of its poorer inhabitants, too.

Other taxes included duties on imported goods, notably on slaves bought from outside the empire. The duties were relatively easy to collect as the state controlled most of the access points open to merchants. Traders were also hit by a ban on private loans, and shipowners could only raise money through the state, which charged 17% interest (the usual being below 6%). Finally, a tax on inheritance was introduced. It seemed that having an accountant as an emperor had its consequences.

As one might expect, Nikephoros' taxes were not very popular, especially with the Church who not only suffering under them itself also saw them as an unnecessary burden on an already impoverished peasantry. Monasteries were targeted, especially, and their property was often confiscated or they were compelled to host army units unpaid. One of the chief voices in the protests was Theophanes the Confessor (d. c. 818 CE) who wrote his Chronographia history on the period, which predictably, contains an unflattering section on Nikephoros' reign.

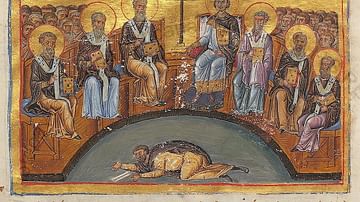

The Church was not pleased with the emperor's choice for the important position of Patriarch (bishop) of Constantinople either. Confusingly selecting his namesake, the scholarly layman Nikephoros I (r. 806-815 CE), the new bishop's support of the second marriage of Constantine VI (r. 780-797 CE) in 795 CE, which had created the Moechian controversy over whether an emperor should remarry, set off yet another round of heated debate and conflict between elements of the Church and the emperor. Nikephoros the bishop had called a synod of clerics and laymen in 806 CE, which recognised the marriage and pardoned Joseph, the priest who had performed the ceremony. Especially unhappy were the monks and followers of Theodore of Stoudios, who had been persecuted for opposing the marriage at the time. The issue would only be resolved when emperor Michael I (r. 811-813 CE) exiled Joseph and recalled Theodore and his followers from exile in 811 CE.

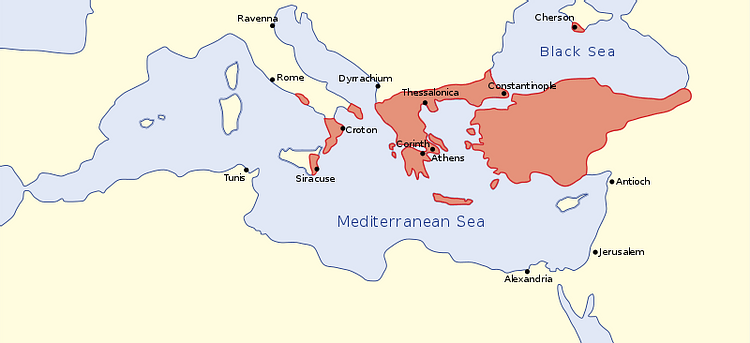

Still, despite these controversies, the emperor's tax reforms did achieve their aim and the state was in a much healthier financial situation than under his predecessors. The army and navy could be paid for and expanded, and the fortifications of Constantinople could be improved too. The empire was further bolstered by the movement of loyal settlers from Asia Minor to Greece, improved defences in Greece and the creation of new military provinces (themes) across the Balkans. These provinces were Thrace, Macedonia, Kephalonia, Dyrrachium, and Thessalonike, with Thessalonica as its capital.

Foreign Policy

Having improved the military muscle at his disposal, Nikephoros set about using it to good effect. Victories came against the Slavs in the Peloponnese and Serdica region of Bulgaria. A minor skirmish with Charlemagne and the Franks over Venice was settled by a peace treaty in 807 CE, although another naval encounter occurred in 810 CE when the doge Oblerius proved disloyal to Byzantine rule.

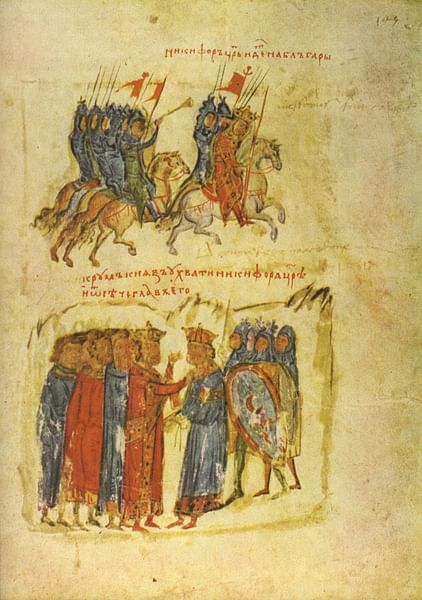

The Bulgars, unified and led by their charismatic Khan Krum (r. c. 802-814 CE) were now proving particularly troublesome. In 808 CE Krum wiped out a Byzantine army near the river Strymon, and in 809 CE he did the same to the Byzantine garrison at Sofia. He also managed to seize the treasure chest of the army containing 80,000 gold coins. Nikephoros responded admirably to these blows by assembling a large revenge force and sacking the Bulgar capital at Pliska in 810 CE, and again in 811 CE when men, women, and children were mercilessly butchered. The fortress at Sofia was also rebuilt.

Elsewhere was a different story, though. In 803 CE a serious revolt was led by Bardanes Tourkos, a military commander of five provinces in Asia Minor. The revolt only lasted a month and ended when some commanders switched their support back to the emperor and Bardanes Tourkos retired to a monastery.

A consequence of the Tourkos revolt was that it weakened Byzantine control of Asia Minor, a situation fully exploited by Harun al-Rashid (r. 789-809 CE), leader of the Abbasid Caliphate based in Baghdad, who seized Tyana and Herakleia at the Cilician Gates in 806 CE. A peace between the two states was only achieved in 807 CE and that at the cost of a hefty tribute from Nikephoros to his rival: 30,000 gold nomisma coins per annum.

Even more disastrous was the ongoing campaign against the Bulgars. After the resounding successes mentioned above the fortunes of the Byzantines nose-dived spectacularly. Nikephoros and his army were ambushed near Pliska on 25 July 811 CE. The Bulgars had waited until dark and then, using wooden palisades, blocked both the entrance and exit to a narrow mountain pass in which the Byzantines had camped for the night. The next morning the Byzantine army was trapped and all but wiped out by sword, fire and landslides set off by the Bulgars. Many of the top Byzantine generals were killed in the disaster, and even those few cavalry that managed to escape the debacle were pursued until they fell into a ravine and drowned in the river below.

Most calamitous of all, Nikephoros was killed in the battle, the first Byzantine ruler to suffer such a fate at the hands of foreigners for over 400 years. His body was identified by its purple boots and brought before Krum who had the head cut off and placed on a spike for a few days. Infamously, Krum then had Nikephoros' skull inlaid with silver and converted into a drinking cup which he and his allies used to toast their victory. The Bulgar leader was even said to have kept his souvenir and to have forced visiting ambassadors from Constantinople to drink from it whenever the opportunity arose.

Successors

In 811 CE Nikephoros was succeeded by his son and heir Staurakios (aka Stavrakios). Unfortunately for the empire, Staurakios had been seriously wounded in the very same battle in which his father had been killed. The young emperor succumbed to his wounds only two months after inheriting his title. Next to step up was Michael I Rangabe, husband of Staurakios' sister Prokopia and who was backed by the Patriarch Nikephoros, but he would only last two years. In that brief time, the emperor did manage a peace with Charlemagne in the west and a return of Byzantine possessions on the Adriatic coast. Once more, though, the troublesome Bulgars were responsible for an imperial change when they defeated Michael's army in 813 CE. Obliged to abdicate after the debacle, Leo V the Armenian, a prominent general, then took the throne in the same year. He would bring a measure of much-needed stability and reign until 820 CE.