Ninurta (identified with Ningirsu, Pabilsag, and the biblical Nimrod) is the Sumerian and Akkadian hero-god of war, hunting, and the south wind. He first appears in texts in the early 3rd millennium BCE as an agricultural god and local deity of the town of Girsu (as Ningirsu) and the city of Larak (as Pabilsag), both Sumerian communities.

His role as a god of agriculture changed as the cities of Mesopotamia increasingly militarized and began campaigns of conquest, one city against another. Scholar Stephen Bertman writes:

Ninurta began his divine career as a god of irrigation and agriculture. In fact, "The Instruction of Ninurta" is the title of an ancient Sumerian "farmer's almanac". But with the rise of imperialism he was transformed into a young and vigorous god of war. (124)

Ninurta was the son of Enlil and Ninhursag, but in some stories, Enlil and Ninlil. His wife was Gula, the goddess of healing (though in earlier inscriptions, as Ningirsu, he was married to the goddess Bau (also known as Baba, goddess of dogs, who becomes Gula). Although he was chiefly defined by his aggressive nature, he was also associated with healing and protection (hence his association with Gula) and was frequently invoked in magical spells to ward off danger, demons, and disease.

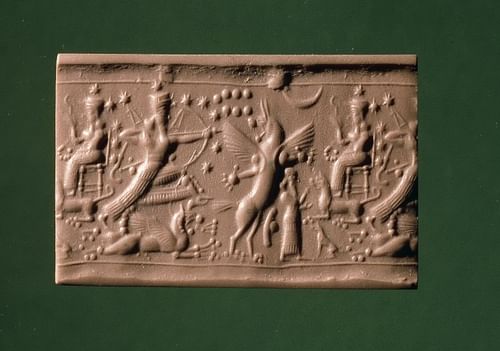

He is most often represented as a warrior, sometimes with upraised wings, holding a bow and arrow and carrying his famous mace Sharur, a weapon capable of speech and reason. In Babylonian art, he stands or runs on the back of a scorpion-tailed lion-beast. Still, as late as c. 1500 BCE, he was still associated with agriculture, growth, and the harvest, depicted as a fully realized individual capable of great deeds but also as flawed as any mortal.

The Assyrian and Neo-Assyrian empires embraced Ninurta as the son of their god Assur, and under the reign of Ashurnasirpal II (884-859 BCE) a great temple and ziggurat were built to the god in Ashurnasirpal II's new city of Kalhu. Seals from this time represent Assur as the winged disc, with Ninurta's name beneath, clearly suggesting the two were regarded as almost equals.

Ninurta was invoked by numerous kingdoms and principalities in ancient Mesopotamia, whether for protection or aid in military matters, from c. 3300 - 612 BCE, when the Neo-Assyrian Empire fell to invaders and many of their gods fell out of favor. Early in his career, however, he was envisioned as the polar opposite of a war god.

Ninurta's Origin & Significance

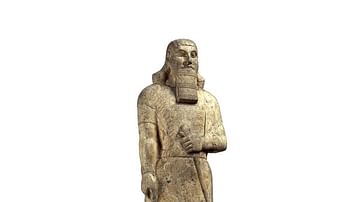

The god originated as Ningirsu ('Lord of Girsu') in Sumer, and the earliest texts use this name for the son of Enlil and Ninlil (although one myth suggests he is the son of Enlil and a she-goat). Gudea of Lagash (r. c. 2144-2124 BCE), noted for his piety and devotion to the gods, dedicated himself to Ningirsu, and his successor, Ur-Ningursu, would take the god's name to honor him. Gudea is probably best known for the Gudea Cylinders, two terracotta cylinders (dated to c. 2125 BCE) which record his dream in the text known as The Building of Ningirsu's Temple, the longest text in Sumerian yet discovered.

Ningirsu was already recognized as a war god by the 2nd millennium BCE where he is featured in the Babylonian work The Epic of Anzu. This myth would be revised during the 1st millennium BCE with Ningirsu's name changed to Ninurta. The god was already known by this later name (whose meaning is unknown) by c. 2600 BCE, and even though Ningirsu would continue to be referenced in Sumer, Ninurta would be the name most Mesopotamians knew and used. Even though he was considered a great warrior-god, champion of the gods, and protector of humanity, Ninurta continued to be associated with agriculture.

The Sumerians are well known for their technological inventions and innovations, and these were notably employed in early agriculture. Orientalist Samuel Noah Kramer writes:

Some of the more far-reaching technological achievements of the Sumerians were connected with irrigation and agruculture. The construction of an intricate system of canals, dikes, weirs, and reservoirs demanded no little engineering skill and knowledge. Surveys and plans had to be prepared which involved the use of leveling instruments, measuring rods, drawing, and mapping. Farming, too, had become a methodical and complicated technique requiring foresight, diligence, and skill. It is not surprising, therefore, to find that the Sumerian pedagogues had compiled a "farmer's almanac" that consisted of a series of instructions to guide a farmer throughout his yearly agricultural activities. (104-105)

This manual, the world's first farmer's almanac, dates to between 1700-1500 BCE and begins almost like a fairytale with the line, "In days of yore a farmer instructed his son..." and then goes on with practical instruction on how to get the most from the land. The piece goes into details on how to prepare the earth, how to plant the seed, even how to drive away birds, and the proper way to harvest the crop.

Throughout the 35 lines of text, it seems as though this advice is being given by a father to his son, but in conclusion, the tablet reads, "These are the instructions of Ninurta, son of Enlil. O Ninurta, trustworthy farmer of Enlil, your praise is good." The farmer's instructions to his son, then, were given divine authority.

Ninurta's power and position in the Mesopotamian Pantheon would have lent significant weight to any document attributed to him, and especially so considering he would have had to take time out from heroic feats to offer his suggestions. The myths concerning Ninurta share many characteristics with those of the Babylonian god Marduk and the later Greek hero Heracles (Roman Hercules) in that he triumphs over the forces of chaos and establishes order (like Marduk), but his pride, like Hercules, can sometimes get the better of him.

Ninurta in Myth

In The Epic of Anzu (also known as The Defeat of Zu), the Anzu bird has stolen the Tablets of Destiny from Enlil. These tablets hold the fate of gods and mortals and, equally important, legitimize the rule of whomsoever holds them. The Anzu bird, a divine creature of enormous size, waits for his chance to steal the tablets and one day, as Enlil is washing his face, the bird swoops in and snatches them.

He flies away while Enlil asks for help from the other gods. Only Ninurta comes forward and pursues the Anzu. The Tablets of Destiny, however, have the power to turn back time, and when Ninurta fires his arrows at the bird, they fall apart mid-air and revert to their components: the shafts return to the canebrake, the feathers to birds, the tip to the quarry. Even Ninurta's bow goes back to the woods and the bowstring to a sheep. Ninurta is driven back by the Anzu but calls upon the south wind, which tears the bird's wings off, dropping him to the ground. Ninurta then slits the Anzu's throat and brings the Tablets of Destiny back to Enlil.

In the poem Lugale (also known as The Exploits of Ninurta), the hero must face the demon of sickness and disease known as Asag (also Agag) who lived in the underworld. This conflict is not initiated by Asag, however, but by Ninurta's mace, Sharur, who encourages him to go battle the demon by praising Ninurta's strength, courage, and skill, and telling him how easy it will be to defeat the creature.

Ninurta goes to meet Asag in battle, but the demon is not alone; he has assembled an army of rock monsters and rebellious plants who march toward the hero. Ninurta is afraid (the text reads he "flees like a bird"), but Sharur tells him to turn around and face his enemies, encouraging him with reminders of past glories and the great fame he will win in victory. Ninurta destroys Asag and his army with his mace, great bow, and the other weapons he has in his belt.

Asag and his followers, however, kept the primeval waters of the underworld in check, and with their deaths, the brackish waters rise to flood the land. Nothing can grow because no fresh water can feed the crops. Ninurta took hold of the corpses of his enemies and piled them up to form a wall around the land and then piled them higher into a mountain to keep the waters of the underworld in place and then raised the River Tigris to water the land. The text reads:

Behold, now, everything on earth/Rejoiced afar at Ninurta, the king of the land/The fields produced abundant grain/The vineyard and orchard bore their fruit/The harvest was heaped up in granaries and hills/The lord made mourning to disappear from the land/he made happy the spirit of the gods. (Kramer, 152)

Ninurta's mother, Ninmah ('Magnificent Queen'), comes from heaven to rejoice at her son's victory and he dedicates the mountain of stone to her honor, renaming her Ninhursag ('Lady of the Mountain'). The goddess Nisaba appears to record Ninurta's triumph and Ninhursag's new name, and the poem ends with praise for the art of writing which preserves such moments eternally.

In the story of the Slain Heroes, Ninurta must defeat an assortment of strange creatures including the Six-Headed Wild Ram, the Palm-Tree King, the Strong Copper, and the Seven-Headed Snake. Some of these monsters are inanimate objects, like the Magillum Boat which brought the souls of the dead to the underworld, and others symbolize valuable material like Strong Copper. This myth with its theme of successive trials and victories is thought to have contributed to the Greek story of the Labors of Heracles.

Like Heracles, Ninurta is not always seen as the heroic champion, however, and in the story Ninurta and the Turtle, his pride overtakes his reason. The tablet is broken toward the end, and part of the introduction is missing, but the story seems to be set after Ninurta has defeated the Anzu and Asag and is being honored by Enki. Ninurta has brought a chick from the Anzu bird to the absu (the primeval watery depths) of Enki's home at Eridu.

Enki praises Ninurta for his victories, for bringing the offspring of his enemy to Eridu, for returning the Tablets of Destiny; but Ninurta is angered by the accolades. He wants to achieve even greater victories and "set his sights on the whole world." Enki reads his thoughts and fashions a giant turtle which he releases behind the hero. The turtle bites and holds Ninurta's ankle, and as they struggle, the turtle digs an enormous pit with its claws which the two fall into.

Enki then looks down into the pit, where the turtle is chewing on Ninurta's feet, and mocks him saying, "You who made great claims - how will you get out now?" The conclusion is lost, but the turtle and the pit were intended to humble the hero and force him to recognize his limitations and also accept with gratitude the praise for his achievements instead of desiring greater glory, and it is assumed that Enki's scheme succeeded.

Ninurta in the Neo-Assyrian Empire

Even so, the glory he sought in the tale of the turtle was freely given by the great kings of the Assyrian Empire. Tukulti-Ninurta I (r. c. 1244-1208 BCE) honored the god by taking his name and invoking him in battle, crediting Ninurta with his spectacular military victories and successful reign. Tigleth Pileser I (r. c. 1115-1076 BCE) honored the god, as did Adad Nirari II (r. c. 912-891 BCE) and many others. No Assyrian king outdid Ashurnasirpal II, however, who built the city of Kalhu as the capital of the Neo-Assyrian Empire with the great Temple of Ninurta as his first project, decorating the walls with reliefs honoring the god's triumphs.

One of the most famous Mesopotamian reliefs, often used on book covers or magazines dealing with the Near East, is of Ninurta and the Anzu bird from the temple at Kalhu. This temple not only served as a place of worship for the god but ministered to the poor, orphans, the homeless, and found work for itinerant laborers. The city's great temple and nearby towering ziggurat dedicated to Ninurta were known far beyond the boundaries of Mesopotamia.

The fame of the hero-god Ninurta, as well as his city, is attested to in the Bible where Ninurta is known as Nimrod, who is described as "a mighty hunter" and Kalhu is given as Calah, "a great city" (Genesis 10:8-12). The name Nimrod, altered to Nimrud, would attach itself to the city of Kalhu in the 19th and 20th centuries when archaeologists took it for the city of Nimrod of the Bible.

Some scholars have suggested that the biblical figure Nimrod is Tukulti-Ninurta I, but this claim is untenable. Tukulti-Ninurta I had nothing to do with Kalhu whereas Ashurnasirpal II more or less dedicated the entire city to Ninurta, and it would be this association remembered by the later Hebrew scribes who wrote the Genesis narrative.

The later Neo-Assyrian king Sargon II (r. 722-705 BCE) built his city of Dur-Sharrukin ('Fortress of Sargon') between 717-706 BCE and moved the capital there, but Kalhu continued to be highly respected; the queens of the empire were buried at Kalhu and the kings at the traditional site of the city of Ashur. During this period, Ninurta lost prestige because Sargon II favored the god of writing, Nabu, who was also considered a son of the high god Assur. Sargon II's successors, however, again elevated Ninurta, and he is mentioned frequently during the reigns of Esarhaddon (681-669 BCE) and Ashurbanipal (668-627 BCE).

Ashurbanipal was the last great king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire and, after his death, the cities were sacked and looted in 612 BCE by a coalition of Medes, Babylonians, Persians, Scythians, and others who saw their chance to free themselves from Assyrian rule and took it. The great cities of Nineveh, Kalhu, Ashur, and the others were destroyed and the statues and temples of the Assyrian gods thrown down. Ninurta suffered the same fate as the other gods who had become closely associated with Assyrian rule, but the hero-god lived on through his influence on stories and myths of other cultures such as those of Greece and Rome.