Noh (Nō) theatre is a Japanese performance art which became especially popular from the 14th century CE and which is still performed today. Noh actors, who were always male in the medieval period, famously move and make gestures in a very slow and highly stylised manner while they wear masks of particular designs which show the characters they are playing such as youths, aristocratic women, warriors, and demons. Greatly influenced by religious rituals and Buddhist themes, the plays are often concerned with moral dilemmas and the next life.

Origins

Noh theatre, with nō meaning 'ability' or 'talent', has its origins in the rituals involved in the ancient Buddhist and Shinto religions and three earlier forms of dance and music which went back to the 12th century CE or even much earlier:

- Dengaku - the rites and rituals traditionally performed by troupes at temples and by peasants at harvest time.

- Sarugaku - a combination of fast dancing, humorous recitals, and acrobatics, also performed by professional troupes.

- Bugaku - the traditional masked dances of the Japanese imperial court introduced from China.

Bugaku, in particular, grew in popularity thanks to the patronage of the shoguns, the military leaders of Japan, who made them an official performing art used for ceremonial occasions during the Edo Period (1603-1868 CE). Noh theatre evolved from this and particularly flourished amongst the warrior class. The genre was also associated with the upper classes of Japanese society. There was, too, a strong association with Zen Buddhism in terms of both themes in the plot and aesthetics, in particular, the idea of karmic consequence and the impermanence of life.

The Stage

The stage of a Noh drama has certain standard features. It is usually square, measures 6 x 6 metres (20 x 20 ft) and, like Shinto shrines, is made of sacred cypress wood and has a small gabled roof. There are few if any sets and little decoration, perhaps only some sand and a pine tree (either real or painted). There are, too, very few props used by the actors - perhaps a hand fan, parasol, a bell, or a letter. As a result, the focus of attention is always on the actors and their movements. There is sometimes a bridge which leads off the stage or merely a curtain which allows the actors to depart to change their costumes. One significant presence on the stage, which can be seen by the audience, is the orchestra. This is composed of drummers, flautists, and a vocal chorus typically composed of eight singers.

The Actors

In the medieval period women were not permitted to perform in Noh theatre, perhaps because of the influence of male-dominated Buddhism, and so all roles - both male and female - were played by men. Another reason may have been that although professional actors sometimes had their own fan clubs, they did not enjoy a particularly high social status in Japanese society.

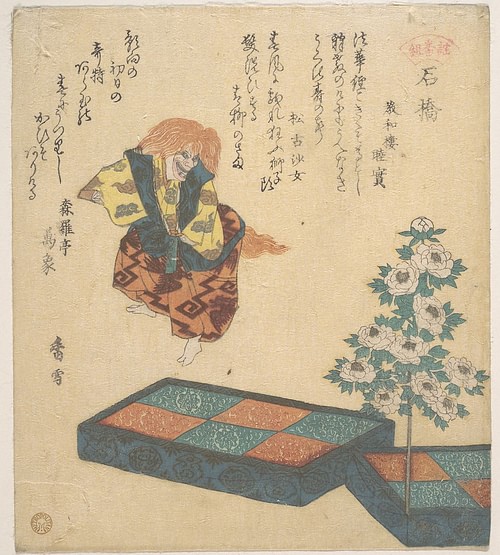

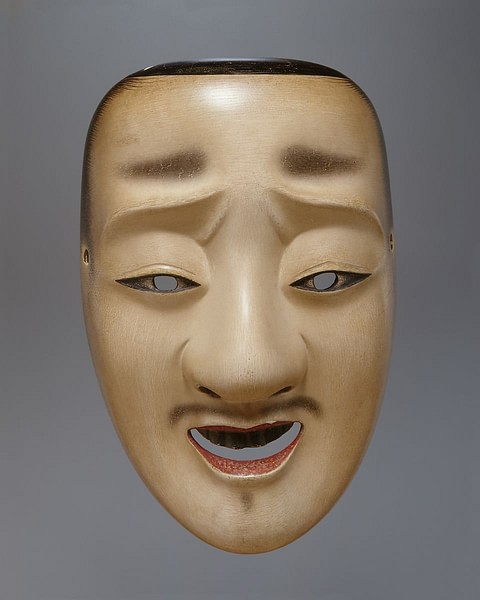

The main performers in a Noh drama wear masks which are made to represent certain stock characters such as young women, old men, warriors, priests, spirits and demons. The masks even have their own names such as that representing a young woman, the Ko-omote. There are two main roles in a play: the leading character (shite) and the second character (waki). The second actor may have a follower or companion (tsure). Only these three actors wear masks.

As the main actors rarely speak any lines, occasional characters such as ghosts and wandering monks often add commentary to the action of the play to help explain the significance of the highly stylised movements of the principal actors. Sometimes, too, actors deliver portions of famous Japanese poems (waka) by way of mini-interludes between dramatic scenes.

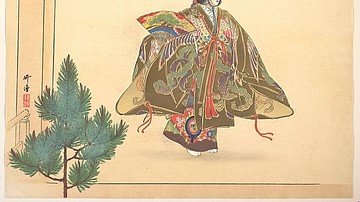

Costumes, originally based on the clothing worn at the medieval imperial court, are extremely elaborate and can be divided into three categories:

- Kisuke - inner garments

- Uwagi - outer garments

- Hakama - trousers.

The designs of these costumes, with gold, red and yellow predominating, are closely related to the specific character the actor is playing, although even a peasant character wears a lavish costume on the Noh stage. In addition, the fabrics varied as there were four distinct types:

- Kara-ori - a rich brocade

- Atsu-ita - made of silk

- Nui-haku - with embroidered and gold leaf designs

- Suri-haku - where only gold leaf is used for designs.

Thus attired in their masks and finery, actors move across the stage and make gestures in a very slow and highly stylised manner to the accompaniment of music. The gestures and movements, known as kata, follow set patterns so that a knowledgeable audience can determine their significance. For example, turning the head in a new direction can mean the character has travelled to a new destination or a few steps may signify a long journey being undertaken. One peculiarity is that actors typically keep their heels on the floor when walking which makes them appear to glide across the stage. Some gestures represent the emotions the character is feeling at that moment.

Famous artists and innovators of Noh include two of its founders: Kan'ami (aka Kanze Kiyotsugu, 1333-1384 CE) and his son Zeami Motokiyo (aka Kanze Motokiyo, 1363-1443 CE), who were actors, directors and playwrights of the genre. Zeami, who also wrote many treatises on the subject, was particularly concerned with catching an ethereal and unworldly combination of beauty, tranquillity, and elegance in the performance, a state he likened to the perfection of 'snow piled in a silver bowl.' Atsumori or 'Birds of Sorrow' is considered Zeamis' great classic.

The Plot

The plot of a Noh play often involves the well-known stories of famous historical and literary figures, especially tragic military encounters, while a strong moral message can be reinforced by the punishment of misdeeds in the afterlife of certain characters. Just like in western opera, written texts were produced for the audience to read before or during the performance so that they could better follow the story. As mentioned, they contain a mixture of prose (kotoba) and poetry (utai), but it was, above all, the physical performance of the actors and their execution of classic Noh gestures that most impressed audiences.

Generally, a Noh play has three main sections:

- Introduction (jo) - the secondary character takes the stage and explains the setting of the story. The tempo is slow.

- Development (ha) - the main character takes the stage and there is an exchange between the two principals where significant events are explained relevant to the story.

- Climax (kyu) - the main character appears in a different mask representing his true identity. He receives help of some sort from the secondary character and is thus freed from whatever moral or physical dilemma he has found himself in.

There are around 250 classical Noh plays and a medieval audience would have usually seen five of them in one sitting. Typically, one play would be selected from each of the following five categories and performed in the following order:

- God Plays (kamimono) - a play with a religious theme, usually with a deity as the main character.

- Warrior Plays (shuramono) - aka hero plays, where the main character is a doomed warrior or male character, most often a figure from the Gempei War (1180-1185 CE).

- Women Plays (kazuramono) - aka wig or heroine plays, where an aristocratic woman is the main character. There is usually much less action in these compared to the other plays.

- Miscellaneous Plays (kyjomono and genzaimono) - typically a play where the plot revolves around the emotions of a 'real' person such as love, jealousy or courage.

- Demon Plays (kiri no) - where the characters are deranged or obsessed women, demons, and ghosts.

In addition to this classification, plays are also divided into the four seasons and only performed at that specific time of year.

Legacy & Modern Noh

Noh theatre had an immediate effect on contemporary society because it deeply influenced the fashion of the aristocracy and military leaders of Japan who greatly enjoyed wearing the richly embroidered costumes made famous by Noh actors. Noh also had a hand in creating a whole separate off-shoot genre. This is Kabuki, which developed from the Kyogen ('wild words') genre of short comical or satirical acts which were first performed during the intervals between the acts of a much more serious Noh play. Kabuki would establish itself as another very popular form of theatre from the 17th century CE with its combination of lively dancing and music performed by actors who wore costumes similar to the clothing worn by ordinary Japanese.

Noh theatre suffered when its greatest sponsors, the shoguns, fell in 1867 CE, but it had long been in decline since its heyday in the 15th and 16th century CE. Still, against all expectation for such a specialised genre where a deep knowledge is required of the viewer in order to appreciate what is going on, Noh made something of a comeback in the second half of the 20th century CE. Noh plays, although mostly staged for a small connoisseur audience, continue to be performed today in all the major cities of Japan.

This content was made possible with generous support from the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation.