The Mediterranean Sea was the economic focal point of the Roman Empire. Rome's armies first established an empire across these waters beginning back in the times of the Roman Republic. In 200 CE, the Mediterranean was still the channel that connected the vast Roman Empire. The greatest imperial cities were located along the seacoast, and ships could cross the waters in a fraction of the time it would take to traverse the empire on land. Among the ships that carried people, news, and goods across the Mediterranean were vessels from North Africa. The region held a special position inside the Mediterranean economy as it contributed a variety of goods to the markets of the empire, notably grain, olives, slaves and pottery. North Africa's loss to the Vandals in 439 CE greatly affected the economy of the Roman world, but it did not end North Africa's important role inside the Mediterranean economy. The wares and grain of North Africa continued to flow out across the Mediterranean, just in a changed position of trade between different states rather than a single monolithic empire.

Late Roman North Africa

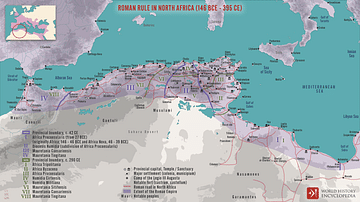

North Africa, as defined by the Roman Diocese of Africa, was the region from the Straits of Gibraltar to Tripolitania, or present-day Libya. The province of Africa, roughly corresponding to present-day Tunisia, had its capital at Carthage, one of the five largest cities of the Mediterranean world at this time. This region had been an important province in the Roman Empire since the conquest of Carthage in the 2nd century BCE but it gained added significance in the 3rd century CE. The 3rd century CE was a time of crisis in the Roman Empire: emperors rose and fell by the year, civil wars raged, and persecution was rampant. Many Roman provinces were damaged by this strife and suffered economic downturns. North Africa, by comparison, was relatively unscathed. The region only had two connections to the civil strife of the 3rd century CE. Septimius Severus (r. 193-211 CE) came from this region, but his reign predated the main chaos of the century, which began in earnest after 235 CE. The imperial claimants Gordian I (r. 238 CE) and Gordian II (r. 238 CE) lost the Battle of Carthage, where their imperial ambitions were cut short. North Africa was mostly spared from the battles of the next century. North Africa managed to produce large amounts of produce during this period while other regions suffered economic downturns due to armies damaging their land, population, and crops. In addition, low amounts of piracy during the 4th century CE benefited trade and access to ports, which was of great benefit to North Africa and its extensive trade routes in the Mediterranean.

North Africa produced large quantities of olives for trade throughout the Mediterranean during late antiquity. Olives were not native to the region, but had been introduced from the east. North Africa proved ideal for the crop, which grew easily in the hot, humid Mediterranean climate around Carthage. Olives held an important position in the diet of peoples throughout the Roman Empire. Olive oil was the lifeblood of Mediterranean diets, as much during the Roman Empire as today. In addition, olive oil was used for lighting lamps. Olive oil could be transferred by ship relatively easily in jars or amphorae and was not very perishable. These traits allowed it to be easily transferred to other ports, especially the Western Mediterranean, where regions like Southern Gaul could not produce olives on the same scale as North Africa.

A variety of other goods, including garum and pottery, were produced in North Africa for trade across the Mediterranean. Fishing was an important part of commerce and garum, a fermented fish paste, was produced and transported to various other ports. Garum constituted an important part of the Mediterranean diet, especially since fresh meat or fish was not always available, and was thus in demand as a source of protein.

Crafts such as pottery were also traded across the sea. African red slipware was incredibly popular and is one of the most widely dispersed types of pottery found in the territory of the old Roman Empire. Archaeologists have found samples of African red slipware in most of the major cities of the empire as well as the majority of the provinces. The pottery also enjoyed a relatively long period of popularity, being traded up into the 7th century CE, when North Africa was under Byzantine rule.

Slaves were also traded from North Africa with the rest of the Roman Empire. Slavery did not experience any noticeable growth during the period from 200 to 500 CE, but the slave trade was still an important aspect of the Mediterranean economy. Slaves could be captured from the autochthonous tribes of North Africa and traded around the Mediterranean as laborers, household slaves, and even entertainers in games. Although the North African region was by no means the only or necessarily even the primary producer of slaves, the area still held an important position in the slave trade.

One of the most important goods produced in North Africa was grain, especially wheat. The province of Africa was especially fertile and it had the ideal soil and climate to produce vast amounts of wheat. Since the city of Rome had long since outstripped the size where just the surrounding villages could produce enough grain to feed the population, North Africa had long shared a special relationship with Rome relating to the grain trade. By the reign of Augustus, Rome was expanding to several hundreds of thousands of people and the city would maintain a vast size into the 5th century CE. The province of Africa had a specific task in the imperial system: it had to provide Rome with grain. Many tons of wheat and barley from Africa and Egypt were loaded onto barge fleets that carried grain to the city of Rome to feed its many inhabitants. Some of this grain went to the annona, or grain dole, to feed the city's poorest citizens for free. These trading relationships sustained the city of Rome, and it became dependent on the North African grain fleets.

Arrival of the Vandals

These relationships became increasingly important in the 4th century CE. The grain fleets from Egypt were diverted to the fast-growing city of Constantinople after its foundation in 330 CE. This left North Africa as the primary guarantor of grain for Rome. North Africa, the furthest Western Roman province from the invading barbarians, maintained its safe position for a time, but in 429 CE the Vandals landed there. By the end of 439 CE, the Vandals had taken Carthage and the rest of the region. This had immediate, drastic consequences for the Roman economy. This greatly hurt the supply of food to Rome and Italy in general. Rome lost its annona since North Africa and its important supplies of grain were now controlled by the Vandals. However, the Vandal conquest did open North African grain to more markets. North Africa, despite its new rulers, was too deeply embedded in the Mediterranean economy to just disappear from it instantaneously. Although the Vandals occupied and re-divided land in North Africa, the region was still a productive and relatively prosperous one. Modern scholars Andy Merrills and Richard Miles cite the continued trade of African red slipware during both the Vandal and Byzantine periods to show that trade did persist and was not stopped by the Vandal occupation (Merrills and Miles, 150).

In addition to being the greatest grain-producing region of the Western Roman Empire, North Africa was also the wealthiest. North Africa was a significant source of wealth from taxes for the Western Roman Emperors and would serve the same purpose under the Byzantine Empire in the 6th and 7th centuries CE. North Africa, due to its minimal damage during the crisis of the 3rd century CE, was still wealthy, but it had always had substantial wealth in its prosperous land, especially compared to other regions in the western half of the empire. Once the Vandals took North Africa, this substantial financial wealth and potential tax income was lost to a Western Roman Empire that was already facing significant financial shortages.

In addition to its wealth, Carthage also served as an important coin mint in both Roman and Vandal times. Carthage was one of the largest mints in the Roman Empire, which befitted the large city, and Roman coins inscribed with “Karthago” have been found across the Mediterranean. The Vandals later created their own bronze coinage, complementing older Roman coins as the currency of the region. In addition, substantial amounts of wealth were stored in Carthage by the Vandals, especially after the Vandal sack of Rome in 455 CE. After the capture of Carthage, Vandal piracy was widespread in the Mediterranean, inflicting damage as far as Greece. North Africa, however, as the core of the Vandal Kingdom, was not damaged by Vandal piracy and its ships could still trade at various Mediterranean ports. Ships were a substantial and risky investment in the ancient world given the danger of storms and pirates, but having the Vandal pirates as their rulers only helped North African ships safely arrive at their ports of call.

Conclusion

North Africa was a crown jewel of the Roman Empire. Its wealth was broad-based in a variety of commodities such as olives, fishing, ceramics, and grain. The vast amounts of grain produced in North Africa were crucial for sustaining Rome through the annona. North Africa's wealth was also important for the financial state of the Roman Empire, especially in the western half, where it was the wealthiest province. North Africa's trade extended across the Mediterranean world and the Roman Empire, as represented by the breadth of African red slipware, which has been found from Gaul to Constantinople. Roman gold solidi were minted at Carthage, one of only a limited number of official Roman mints, and coins from Carthage have been found around the Mediterranean. The Vandal occupation of North Africa caused significant consequences for the fading Roman state. The loss of the annona and of North Africa's wealth greatly hurt the already significantly declining Western Roman Empire. Vandal occupation, however, did not end North Africa's integration into the greater Mediterranean economy. The trade of North African goods continued during the Vandal era and agriculture was still producing substantial amounts of crops, even after the initial damage by the sometimes violent Vandal occupation. North Africa remained an important part of the Mediterranean economy during the Late Roman and Vandal periods, and North African trade and wealth were integrated into the greater spheres and markets of the Roman and Mediterranean worlds. The Vandal occupation of North Africa did not end the economic importance of North Africa in the Mediterranean but merely redefined it, changing the manner in which North Africa fit into the broader economic system. North Africa was still an important component in the Mediterranean economy; it was just no longer a component of the Roman Empire.