While little is written about Parthian-Scythian relations, not only did the Parthians share origins with the Scythians and cooperated militarily but social, cultural, and commercial interactions were likely as well. Essentially leading a life of nomadic tribes - riding horses, tending herds, and living in covered wagons - Scythian tribes are often mentioned in ancient sources. While their ascendancy in Central Asia spanned between the 7th and 3rd century BCE from areas around the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, the extent of their territory ranged west into Thrace, then east across the steppe of Central Asia to the Altai Mountains of Mongolia. But sometime around 330 BCE, after the Scythian nadir, the Parthians would begin their ascendancy. Known as the Parni, and Scythians themselves, they moved south off the steppe, east of the Caspian Sea, into the Seleucid province of Parthia. Using Scythian military tactics, they would take over Parthia, and finally, the Seleucid Empire, and become known as Parthians.

Military Alliances, Conflicts, & Influences

Having cultural origins and being neighbors besides, military cooperation between Scythia and Parthia would naturally happen. Even when they did war, their argument was about Scythian support. After the Parthians agreed to pay the Scythians to help secure Syria from the Seleucid ruler Antiochus VII (r. 138-129 BCE), the Parthians - perhaps impatient in waiting - engaged and won without them. When the Scythians later demanded payment, the Parthians refused. That apparently sparked a Scythian revolt in which Parthia's king Phraates II (r. 132-127 BCE) lost his life. This then emboldened Scythian tribes in the east to defeat and kill Artabanus I (r. 127-124 BCE). However, the Scythians came to Parthia's aid later when, after dynastic trouble, the Parthian king Sinatruces I (r. c. 75-69 BCE) was installed to the throne with Scythian help. Moreover, according to Cassius Dio, the Scythians played a key role in the 1st century in helping Artabanus II (r. 12-38/41 CE), himself half Scythian, secure Armenia for Parthia (57.26). Ultimately, as combatants or allies, the Parthians would learn much from the Scythians.

The Scythians had a wide array of weapons. They used battle-axes, maces, lances, swords, shields, and for personal protection, scale armor, and helmets. Scythian tactics included the use of infantry along with their formidable cavalry, and their strategy was often one of attrition in leading the enemy deep into friendly territory, stretching supply lines, then with hit-and-run and ambush tactics finishing their opponents off with their most formidable asset, the bow and arrows shot from horseback. That is what the Scythians did in defeating Darius the Great (r. 522-486 BCE), which gave them the reputation of being invincible. However, after their defeat by Phillip II (r. 359-336 BCE) in 339 BCE and then getting caught in a trap at the river Jaxartes by Alexander the Great (r. 336-323 BCE), the Scythians would never again recover their reputation.

As Scythia's nadir coincided with Parthia's ascendance, the Parthians took valuable lessons from Scythia's successes and failures. Using the same tactics the Scythians used against Darius, the Parthians would win a spectacular battle against the Romans at Carrhae in 53 BCE. Parthian warfare also simplified the Scythian strategy. Rarely relying on infantry, when they did, it was their allies that provided it. It appears the Parthians would also scale back Scythian varietal use of arms, relying only on short and long swords, the lance, and their bows as their cavalry effectively used them.

Taking the strength of the Scythians - their nimble horses and effective use of the bow - the Parthians made critical improvements here too. Though Scythian riders were matchless in their time, Strabo mentions their horses were "small and difficult to manage" (7.4.8). It appears the Parthians indeed bred better horses. While the Medes were already known for their large horses and having pasture that was "peculiarly adapted for breeding horses" (Strabo, 11.13.7), when in the 2nd century Mithridates I (r. 171-132 BCE) added Media to Parthia's territorial gains in 148/7 BCE, access to its pasture and breeding techniques likely played an important role.

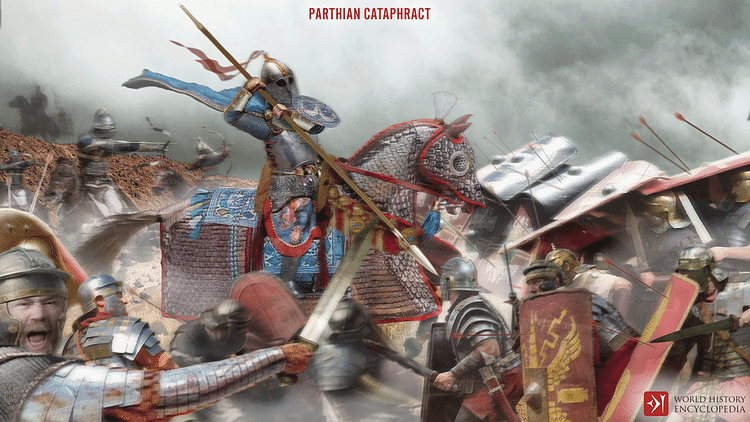

One of Parthia's most significant innovations was their development of the cataphract. Mounted warriors using long lances to stab at enemy lines may have been a maneuver sporadically used early on, but the integrated tactical use of an entirely armored, huge, fast horse mounted by a completely armored rider equipped with a lance and a long sword was something completely new. Working in concert with their light cavalry, when they were not mopping up fleeing combatants or opposing cavalry, the cataphracts were sent into enemy lines at full gallop. Their weight and momentum would punch through, creating openings their light cavalry would pour arrows into. Finally, it appears the Parthians made improvements to the Scythian bow, too. When comparing original pictographic evidence, it certainly appears Parthian bows, in relation to body and horse, were larger. Such development is suggested when Plutarch describes the Parthian bows at the Battle of Carrhae as "large and mighty so as to discharge their missiles with great force, tearing through every covering, hard or soft" (Crassus, 24.4-5).

Contrast of Governance

For both the Parthians and Scythians - known for their military prowess - communal organization of the military would have been an unsung part of their success. A golden beaker manufactured in the 4th century BCE from the Kul'-Oba kurgan in Crimea shows bivouacked soldiers. While two, with spears and bows at the ready, appear to contemplate their fate in upcoming action, one strings a bow; another removes his comrade's tooth, while another bandages a fellow's hurt leg. Another artifact in gold relief from the same kurgan demonstrates a common ritual where two warriors drink together from a horn. According to Renate Rolle:

The two future blood brothers mixed wine with their blood, leant close together and drank the mixture, both lifting the vessel up to their lips. The simultaneous drinking was obviously important; it sealed the bond to the death and perhaps even into the next world. (World of the Scythians, 62)

Such depictions reveal ways of life intended to instill a shared purpose and camaraderie among soldiers, where individuals fighting for friends against foe create a united, more resilient front. It appears the Parthians brought this concept to a new and broader application. Where Scythian loyalty between soldiers was indeed robust, group loyalty was mainly to their tribe and chieftain. Conversely, with a widespread conferring of noble status, Parthian nobles' loyalty and support were closely tied to one king. Yet, as a counterbalance to a king's tyranny, the nobles had a significant say about the balance of power and could (and did more than once) depose a king who was perceived to rule irresponsibly or sought too much power.

While Herodotus refers to Scythian "kings", and some by name, like most tribal people, Scythian governance was more a confederation of tribes and chiefs. Herodotus' account (4.126-142) reveals that while a high king or chief represented the Scythian nation in the messaging between notables, other subchiefs also voiced their opinion and had a significant say in implementing action.

Militarily, the disadvantage of tribal forms of governance is their lack of political cohesion and loyalty to national identity and cause. The advantage for the Parthians is there was no federation of tribes stemming from the Parthians themselves. Though local governors and client kings were allowed a degree of autonomy under Parthian rule, there was only one ruling class. No doubt there was internecine conflict and contenders for the throne, but Parthia's goal was always one king with noble support.

Scythian Nomadism, Parthian Architecture

Perhaps the most significant divergence of the Parthians from their Scythian roots can be seen in their architecture. That does not mean the Scythians lacked architectural types to suit their needs. While it is widely believed they were wholly nomadic, Herodotus mentions two other types of Scythians: the "royal" and the "farming" kind. More than subsistent cultivators, some farmers, in fact, "sold" or exported their products (4.17-20). Not only would these have built permanent homes, since their efforts were likely cooperative they would have developed settlements. North of the Black Sea in today's Dnieper river vicinity, Herodotus also references farmers inhabiting a land "three days journey" wide and "eleven days voyage" long (4.18.2). The size of this district reflects a significant demand for grain products. Architecturally, the logistics of such enterprises would also require a system of warehouses for storage and roads to points of transfer.

As to the royal Scythians, while we have the architecture of their burial mounds called kurgans, of carefully padded earthworks and catacombs, it appears they also resided with a degree of permanency in fortified settlements. The size of the earthworks of the Bel'sk fortification in the Dneiper river valley in Ukraine not only reflects the presence of a significant superstructure (33 km in circumference), indications are it was a center of crafts, wealth, and widespread trade. Even so, as ancient sources attest and as their military organization indicates, the Scythians were mostly nomadic. More than one source mentions their houses on wheels. Pulled by teams of oxen, some house-wagons could have two or three rooms. Depending on the rank of the dweller, floors and walls could be opulently adorned. Moreover, when gathered, the house-wagons would have the appearance of a city.

But as the Parthians stepped off the steppe, they encountered the more settled societies of the Greeks and Persians who themselves had accomplished significant feats of architecture. If they were to take over an empire already of great wealth and infrastructure, they would have to step up to the plate. At Ctesiphon, near Seleucia on the Tigris, the Parthians built housing for their troops "capable of lodging a great multitude" (Strabo, 16.1.16). They also erected many public buildings promoting arts and crafts and other commercial activities. Complete with a palace, they made Ctesiphon the king's winter residence, but for summer, they brought up to speed the fort and city of Ecbatana.

At Hatra, the Parthians protected the city with a three-mile fortified wall so effectively that in the 2nd century it repulsed Roman emperor Trajan's attempt on it in 117 CE and Septimius Severus' in 193 and 197 CE. Within the city, the Parthians built a unique, expansive temple 800-feet long and 700-feet wide. Similar expansion at Merv (Seleucid Antioch) was accomplished with state-of-the-art fortifications of step-shaped battlements and interval towers. In Syria, Parthia made Dura Europas its provincial administrative center, complete with fortified walls, a palace, Mithraim, bazaar, and typical of their multicultural inclination, a Jewish synagogue.

Other projects included the reflourishing of ancient cities like Assur, Uruk, and Nimrud, to include adding fabulous houses and temples with barrel vaulting while incorporating the Parthian architectural innovation of vaulted open-ended entryways called iwans. The influence of the Parthian iwan on Middle Eastern architectural design resonates to this day. Moreover, Assur's wall surfaces were beautifully adorned with tooled stucco using geometric and floral patterns that are also a remarkable precursor of designs adopted by Muslim artists.

Cultural Origins: Art, Music, & Dress

Much that is learned about Scythian culture comes from recent kurgan finds north of the Black Sea. While ancient sources focus on their nomadic warlike character, Scythian burial goods add another layer of understanding to their remarkable cultural sophistication and social vibrancy. Besides the level of intricate craftsmanship in glittering gold, many pieces also tell a life story, for example a comb is not just a comb but is crafted to show warriors in fierce combat. A pectoral or gorget, from the Tolstaya mogila kurgan shows scenes from daily life with exquisite segmented detail in the upper register: the milking of a ewe, two men sewing a shirt, calf and colts nursing. In contrast, the lower register displays dramatic prey/predator scenes of cats taking down a stag and griffins biting and clawing at horses. Then in choice places toward the neck are miniature goats, rabbits, dogs, grasshoppers, and birds.

Thus the Black Sea artifacts offer unique, sometimes dramatic, snapshots of Scythian fashion, interests, beliefs, habits, and daily life visuals like few burial goods do. Many, like the gorget, have prey/predator themes. Other common themes are of recumbent cats or reclining stags. But unique too, akin to modern tastes, was the Scythian penchant that swung from the remarkably realistic capturing of subject matter in mid-action to the abstract rendering of reality. Thus a stag or cat could be accurately portrayed or uniquely stylized.

Furthermore, while the Black Sea discoveries reveal the practical choice of trouser and tunic for horse people in a cold climate, they also show Scythia's love of music and dance. Some items show erotic dancers (again expertly captured in mid-action) swaying to the music. A golden headband showing a man playing the lyre was found at the Sachnovka kurgan, and pan pipes made from bird bones at kurgan 5 at Skatovka. In several tombs at Pazyryk, ox-horn drums were unearthed, and at kurgan 2, an amazing find was made; a harp-like instrument that had at least four strings. Barry Cunliffe describes it as "made from a single hollowed-out wooden resonator, the middle part of the body was covered by a wooden sounding board, while sounding membranes were stretched over the open part of the body" (226-27). The tones issued forth from this instrument by a skilled musician must have been remarkable.

While such instruments would have entertained the Parthians, their almost complete divergence from Scythia's artistic styles likely had to do with the influence of Greek motifs. As they took over the Seleucid Empire, one vestige they would return to, though, was the trouser and tunic outfit - but with exaggerated distinction. Exclusive to the nobles, loose fitted clothing with multiple horizontal pleats became the rave for both sexes. To further accentuate their statement, men's pleated trousers were often ballooned around the legs. Additionally, with puffed hair kept in place with a headband and closely cropped beards and mustache, the dress depicted on some statuary reveals copious amounts of intricate leaf and floral embroidery with vertical rows of brass or precious metal buttons and coins.

Finally, one of the unique identifiers of Scythian art is the plethora of animal art compared to human depiction. In contrast, the Greeks put great emphasis on the human subject. As Parthian art attempted similar emphasis - though the frontality motif, where the subject seeks to communicate with the viewer, was innovative - Parthian technical expertise for realistic depiction fell short. In comparison, the remarkable level of sophistication in manufacture, depiction, style, and vibrancy of Scythian art is peerless.

Religious Origins, Scythian Roots

Like all ancient cultures, worship and symbolism of the elements would have been an integral part of the Scythian belief system. With the flat expanse of the steppe over which they trod, a prominent characteristic in daily life would have been the sky as it met the earth at the horizon. Another manifest feature, from which the steppe offers little escape, would have been the sun. Providing security against wild beasts at night and everyday practical utility in cooking and metallurgy, fire in ancient times was also essential and held considerable symbolic sway. For the Scythians and Parthians, the earth, sky, sun, and fire came to have particular theological value.

Herodotus relates eight deities the Scythians worshiped. Besides Hestia and Zeus, known by the Scythians as Tabitha and Papaeus, there were Api (mother earth), Goetosyrus (Apollo), and Argimpasa (Aphrodite). And though Herodotus omits their Scythian names, he also mentions Hercules, Ares, and Poseidon. While Herodotus understood Scythian belief from his perspective of the Greek pantheon, he says the Scythians had no images, altars, or temples. As Cunliffe mentions: "The deities of the upper ranges of the pantheon do not seem to have been anthropomorphized, or at least no certain depictions of them are known." (276) Initially, then, the Parthian religion would have been primarily a veneration of the elements of fire, earth, sky, and sun. While the doctrines with which the Parthians would later interact would keep these elements, they would be infused more definitively with human characteristics.

Besides the Greek pantheon, the two most widespread belief systems during Parthian times were Zoroastrianism from the Persian Empire and the worship of the god-figure Mithra, who in one person held the attributes of many gods. As Persian and Greek cooperation were essential to Parthia's success, the Parthians flirted with keeping both nation's customs, but once they stood on their own, they began to identify with Mithra, giving them a unique standing and identity different from the Greeks and Persians while providing common ground with both. By choosing Mithra, Parthia could also return to its Scythian roots. After all, Mithra was a god of the elements important to Scythian and Parthian alike, and like both, he was a warrior on horseback.

In conclusion, as neighbors and cousins with common cultural origins, as Parthia retained Scythian influences, its takeover of an empire also necessitated changes. As to culture, both peoples enjoyed similar music and dance, and though the Parthians would take the Scythian dress to an exaggerated level of fashion, their modest facsimile of Greek art would fall short of Scythia's vibrant talent in gold. But architecturally, as they took over urban areas and built on a grand scale, Parthian creativity shone through with an innovative employ of circular motifs, geometric decor, and iwan design. Finally, though they governed differently - the Scythians sticking to their tribal ways, the Parthians ruling with a unique king/noble relationship - they warred similarly. Ultimately, as the Parthians made improvements to their cavalry and weapons, what they learned from the Scythians is what enabled them to conquer and maintain an empire for nearly 500 years.