Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) was a French post-impressionist artist. Although he struggled for recognition in his own lifetime and often lacked confidence in his work, the artist's unique style, use of light and colour, and his interest in geometric forms above realism proved hugely influential on later artists, notably Henri Matisse (1869-1954) and Pablo Picasso (1881-1973).

The archetypal tortured and struggling artist, Cézanne could not get his art exhibited in the traditional galleries and was savaged by critics. He strove to capture the essence and underlying structure of nature and recognition did come towards the end of his life. Cézanne created powerful paintings full of character and colour unlike anyone had ever quite done before.

Early Life

Paul Cézanne was born on 19 January 1839, the son of Louis-Auguste Cézanne, a prominent businessman and banker in Aix-en-Provence. His mother was Anne-Elizabeth-Honorine Auburt. Paul did well at school and won a prize for painting. One of his childhood friends was Émile Zola (1840-1902), the celebrated author. Paul, rather shy, hypersensitive, and at times nervous, studied drawing from 1856 and then law at the university in Aix, but after studying under the painter Joseph Gibert in his spare time, in April 1861, he made the momentous decision to move to Paris and become an artist. Paul studied at the prestigious Académie Suisse where his fellow students included other future impressionists Claude Monet (1840-1926) and Pissaro. This new venture was not a success at first, and Paul returned to his hometown where, of all things for an aspiring artist, he earned a living in his father's bank. He did not abandon art and joined once more the Municipal School of Drawing in Aix.

It was a temporary interruption, and by November 1862, Paul was back in Paris and trying once more to establish himself as an artist, largely a self-taught one (he failed the entrance exam for the École des Beaux-Arts). His father was crestfallen Paul had not joined the family business, but he at least gave his son a monthly allowance to permit him to pursue his dream. This time, his career change was definitive. Paul would return to Aix, but then it was to paint its landscapes and people. In Paris, he studied the works of the great masters in the Louvre and encountered such modern painters as Gustave Courbet (1819-1877) whose thick application of paint using a palette knife was causing a stir. An early Cézanne work is the Study of a Male Nude (1863-1866), and it was his rather odd-looking nude drawings, which caused much discussion amongst fellow artists. The art historian S. Roe gives the following description of Cézanne at this time:

Tall, round shouldered, with short, black hair, swarthy dark skin and a black, drooping moustache, he aroused great curiosity…at twenty-two, Cézanne was intense, clumsy and paranoid; he seemed suspicious of everyone. (15)

The Evolving Cézanne Style

Cézanne quickly established his own style of painting and living. The young artist seems to have been determined to present himself as a poorly-educated country boy, perhaps to make sure more sophisticated artists did not try and dissuade him from the artistic path he wished to take. He was influenced, though, by the art around him. Many of the churches and museums of Aix were packed with baroque paintings on religious themes and dark subject matter. The artist was particularly influenced by the power of Renaissance Art at its best with its sense of drama, dark backgrounds, and strong contrasting colours. More recent artists encountered in Paris like Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863), an exponent of Romanticism, were also an influence.

In the 1860s, Cézanne called his style couillard, or "ballsy", and he was keen for his work to reveal his personality above and beyond the subject matter itself. There are distinct erotic and violent undertones in this period of Cézanne's work. Technically, his approach with the paint itself matched the power of the painting's subject with the "vigorous application of thick tonal slabs of color often laid on to the canvas with a palette knife" (Howard, 114).

Paul Cézanne: A Gallery of 30 Paintings

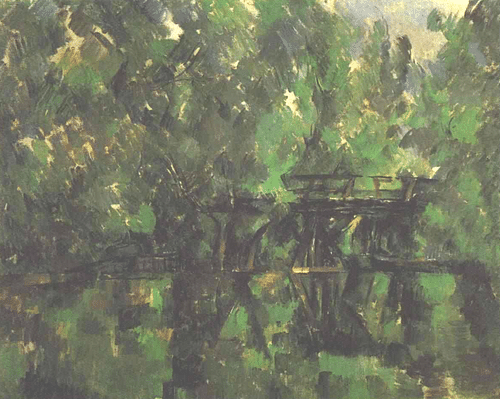

Cézanne, like many great artists, evolved his style over the years. By the end of the 1860s, he began to use a range of much lighter colours, particularly in landscapes. Cézanne relocated to L'Estaque, 50 kilometres (31 mi) west of Marseille, where he concentrated on landscapes before he returned to Paris. Then another change of scenery further developed his art. Cézanne worked at Pontoise near Paris from the autumn of 1872 and then at Auvers-sur-Oise where he painted alongside Pissaro. With him went his mistress Marie-Hortense Fiquet (1850-1922), who was 11 years his junior and a part-time artist's model, and his infant son, also called Paul (b. 4 Jan 1872). The lush green landscape of northern France was a novelty for Cézanne. Pissaro influenced Cézanne who saw "how to organize a dynamic coloristic and tonal balance using the rich greens of the trees and foliage set against the high-toned yellow ochres of the simple houses" (Howard, 110). Both artists in this period frequently used a palette knife to create the solid appearance of colour more typically seen in murals. Cézanne was using ever-lighter colours and became much more interested in showing the effects of light in his work, a central theme of impressionism. Speaking to a journalist in 1870, Cézanne stated "I paint as I see, as I feel - and I have very strong sensations" (Howard, 182). The artist's work would constantly battle to balance seeing and feeling, a battle that preoccupied all of the impressionists. In Auvers, Cézanne found his first purchaser, Dr. Paul Gachet (1828-1909), who would later be famously captured on canvas by Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890).

The Exhibitions

Cézanne, like many other avant-garde artists, found it difficult to break into the well-established and conservative scene of fine art. Submissions to the Salon were rejected. The Salon was an exhibition space in Paris run under the auspices of the French Academy, and it monopolised art from 1667 onwards. Only by exhibiting and selling works through the Salon could an artist hope to gain future commissions and lucrative patrons. After an uproar over just how many artists had been rejected in 1863, a special exhibition was organised, the Salon des Refusés (literally, the Salon of Rejects). Cézanne had a provocative female nude in this exhibition, selected by the artist as a challenge that would invite comment. It was a small victory against convention, but the Salon system was tough to break into. Fortunately, its monopoly was about to be challenged.

Cézanne had a painting in the first exhibition of independent artists in Paris in April of 1874, his House of the Hanged Man (1873). The exhibition, the first independent show from the established art dealers, included many kinds of works and several by other impressionists such as Monet, Edgar Degas, Pissaro, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. For this reason, it has become known as the First Impressionist Exhibition. The month-long exhibition was seen by up to 4,000 people. The sales were not so great, and the press had a field day criticising this new venture which attempted to exhibit and sell art outside of the established Salon system. Nevertheless, the impressionist exhibition was a first strike at the art establishment, and many more would follow. Cézanne was again represented in the Third Impressionist Exhibition of 1877 in Paris, where he had 16 paintings on display. Once again, the conservative critics ridiculed the impressionist painters. Even so, Cézanne never gave up on the Salon. In 1882, he did finally have one of his paintings accepted by the Salon, but it would be the only time in his career after many, many rejections – one scribbled note by a judge recorded that his work was "unsuitable for the dignity of art" (Roe, 44).

The independent exhibitions of the 1870s also allowed like-minded artists to meet and discuss their work, although there were many arguments, too. Paris' Café Guerbois was often packed with artists who are now world-famous. The artist Mary Cassatt (1844-1926) gives the following insight into the character of Cézanne at this time: "When I first saw him, he looked like a cut-throat, with large red eyeballs standing out from his head in the most ferocious manner, a rather fierce long pointed beard…and an excited way of talking that positively made the dishes rattle." Then, on getting to know her fellow artist, she noted he had "the gentlest nature possible" (Roe, 186).

Like other impressionists, Cézanne came in for severe and unrelenting criticism from art critics who simply could not understand his paintings. Neither could most of the public, but they at least knew what they liked even if they did not know why. Still, the strange choice of colours, subjects, and their distorted forms all caused outrage, consternation, shock, and ridicule in equal measure. Living with his controlling father in Aix-en-Provence, any praise for his art from the few who championed the impressionists must have seemed hollow, since the reality was Cézanne could not make a living from his work. Originally fleeing to the south in 1870 to avoid conscription in the army to fight in the Franco-Prussian War, the artist was still obliged to live on handouts from his highly conventional father. Cézanne kept his mistress and son a secret, housing them in a nearby village.

Independence

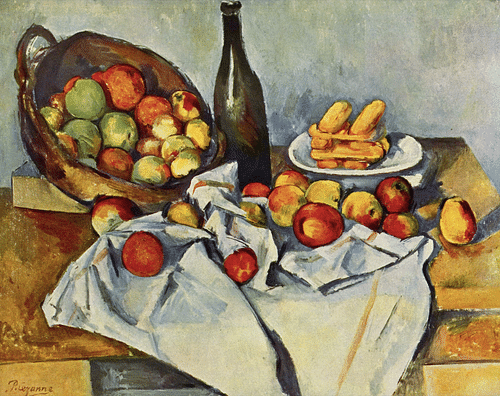

Cézanne painted many still life paintings. His often quirky representations of these humble subjects with their odd assortment of secondary objects was a major force in establishing the idea that even humble fruit and flowers could express great art. As Cézanne noted to friends, "When I use paint to outline the skin of a beautiful peach or the melancholy of an old apple, I catch a glimpse, in their reflections of…their love of the sun; their memories of dew and freshness" (Roe, 255).

Another popular subject that ran through the artist's career was to paint groups of male and female bathers. The artist also captured many of his friends and acquaintances in portraits. An example is Portrait of Victor Chocquet in an Armchair (1877). Chocquet (1821-1891) was a noted collector of art, including the impressionists for whom he became a great champion. Another noted supporter was "Père" Tanguy (1825-1894), who owned an art supplies shop in Montmarte, accepting paintings as payment for materials.

When Cézanne's father died in 1886, he did not need sponsors anymore as he inherited a sizeable sum of money that allowed him to pursue his art entirely independent of any financial pressures or outside influence. Six months before, he had married Marie-Hortense in April 1886. By the end of the 1880s, Cézanne had established himself as an independent artist and he gained favour from the symbolist movement of writers and artists (who reacted against realism in art). In 1889, he had a painting on show at the Universal Exhibition, his House of the Hanged Man. Another exhibition followed in 1890, this time in Brussels.

Now living on his family's estate in Aix, the villa Jas de Bouffan, Cézanne worked in his studio, which was out of bounds for anyone else. The artist, though, concentrated on outdoor work and landscapes in the heady atmosphere of Provence with its pines, rocky outcrops, cicadas, and startling sunlight. He once wrote, "the Sun here is tremendous that it seems to me as though objects were silhouetted not only in black and white but in blue, red-brown, and violet" (Howard, 183). This working outdoors, plein-air, as opposed to sketching a landscape and painting the scene in the studio, was a particular feature of the impressionist movement.

The Mature Style: Post-Impressionism

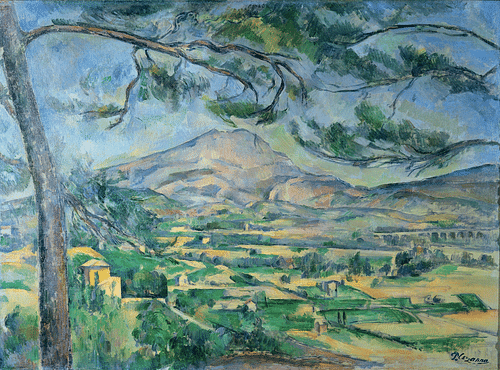

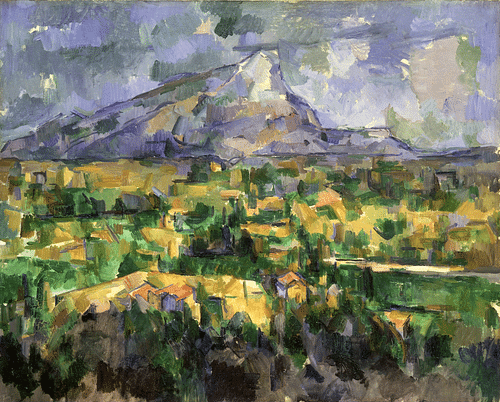

Cézanne's technique had now evolved to use many light and small brush strokes, carefully and precisely building up the painting using dashes, dabs, and repetitive strokes. His palette is now formed with one purpose only: to create a complete harmony of tones. Cézanne recognised this challenge was a formidable one, perhaps even an impossible one, as he noted towards the end of his life: "I have not the magnificence of colouring that animates nature" (Howard, 236) and "I still can’t do justice to the intensity unfolding before my senses" (Roe, 268). He constantly reworked his paintings and signed very few of them, perhaps because he never regarded the challenge as ever having quite been met. Another symptom of constantly facing the same challenge was Cézanne's near-obsession with certain subjects; he painted Mont Sainte-Victoire just east of Aix almost 60 times. These paintings show clearly the artist's progression towards his goal; they are less and less realistic, the colours create the spatial dimension, and nature is distilled into geometric shapes.

Failures were many, and friends of the artist record seeing him give up in despair and leave unfinished paintings in hedgerows. The artist certainly did, though, achieve his other aim, which was not to represent nature (which a camera could now do) but, rather, represent the experience of nature, that is, the feeling not the sight of our surroundings. He wanted to represent perspective through colour alone. He did not want to reproduce reality but create a new one, something parallel to nature. For this purpose, he often used watercolours instead of oil paints to experiment with colours and how they might be built up on the canvas.

Cézanne's ultimate aim was the exploration of underlying structure, permanence, depth, and space, what has become known as post-impressionism. It was a style that rejected the natural realism and preoccupation with the juxtaposition of colours and light of the earlier impressionists. Post-impressionism was about adding permanent emotional expression and symbolism to the transient light and colour effects of impressionism. It is for this reason that Cézanne would study intently and at length any subject he was going to paint before he took up his brush.

As the art historian S. Hodge summarises: "Cézanne treated all his subjects in the same way. Everything had an inner structure, which he described with colour and directional brush marks, and he modelled every object in layered tonal contrasts in order to reveal that structure" (64). This mature style was applied to landscapes, still life, and portraits.

Into the 1890s, Cézanne was beginning to finally establish a reputation. Many critics continued to deride his work, but many other artists were beginning to admire his contribution to the avant-garde movement. There were even some favourable reviews. The cracks in the art establishment were beginning to widen. Some of the collectors who had championed the impressionists were now dead, but the resale of their collections showed a demand for this type of art, including that produced by Cézanne. He received his first solo exhibition of 150 works in Paris in November 1895.

Cézanne's international reputation continued to grow, too, with two works displayed in the Berlin National Gallery in 1897. Cézanne remained almost exclusively in Aix, so much so, he became known as the 'Hermit of Aix', although he spent periods of the year in Paris, too, and he even went abroad for the first time in 1890 when he visited Switzerland. He was particularly revered by young Parisian artists, including many post-impressionist painters who would become household names. Artists and dealers even sought him out in his retreat. Further recognition came with the 1900 Universal Exhibition, the 1901 and 1902 Salon des Indépendants, and the 1904 Salon d’Automne where Cézanne’s works had their own room.

Cézanne worked right up to the end at his final home in Les Lauves, north of Aix after he had been obliged to sell the family estate when his sister wanted her share of the inheritance. He had a studio built at Les Lauves, and it included a view of his beloved Mont Sainte-Victoire. Having suffered from diabetes for some years, he caught a fever while painting in the rain. Paul Cézanne died on 23 October 1906.

Legacy

Cézanne's abilities were recognised by his contemporaries. In a letter to a critic written in 1883, Pissaro made the following comments on Cézanne's work: "Why is it that you do not say a word about Cézanne, whom all of us recognize as one of the most astounding and curious temperaments of our time and who has had a very great influence on modern art?" (Howard, 101). There were still the traditional critics, though, and even some who had formally championed the impressionists but now regarded the techniques they used as not quite successful in achieving great art. Émile Zola was one such figure, and he singled out Cézanne as "un grand peintre avorté," that is someone who did not reach his full potential for greatness. In his 1886 novel L'Oeuvre, Zola's central character, a failed artist, was obviously based on Cézanne. The novel led to an irreconcilable rift between the childhood friends, and they never spoke to each other again.

Zola was wrong about Cézanne. One year after his death, 57 works by Cézanne were part of the Salon d'Automne. They would inspire a whole new generation of artists, among them Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, to change the world of art once more. Picasso directly attributed Cézanne as one of his inspirations in the development of cubism. Picasso, Matisse, and others frequently described Cézanne as "the father of us all" (Hodge, 6). As Cézanne himself had noted, "I wanted to make of impressionism something strong and enduring, like the art of the museums" (Bouruet Aubertot, 344).