Pausanias (c. 510 - c. 465 BCE) was a Spartan regent and general who won glory by leading a combined Greek force to victory over the Persians at the Battle of Plataea in 479 BCE. Famously immodest regarding his own talent, he was beset by accusations of colluding with the Persians throughout his career and, despite success in Cyprus and Byzantium, he would meet a particularly inglorious end. He is not to be confused with Pausanias, the 2nd-century CE Greek travel writer.

Early Life

Pausanias had royal and military pedigree. His father was King Cleombrotus, and his uncle was Leonidas, the Spartan king who had gained glory in defeat at Thermopylae. Pausanias, thus, belonged to the Agiad clan, the senior of the two royal houses at Sparta. Nothing else is known of Pausanias' personal life except that he had a son, Pleistoanax. He first appears in the historical record in 480 BCE when he served as regent for his young cousin Pleistarchus but it was as a general that Pausanias would make his name.

Plataea

In the naval Battle of Salamis in September 480 BCE, Xerxes' planned invasion of Greece had met a serious setback but his massive army was still intact, and if the Greeks were to survive as independent city-states they would have to fight and win on land; the battlefield would be near the small town of Plataea in Boeotia in 479 BCE. Ancient authors may have exaggerated the numbers but even with a more conservative estimate, the battle would involve some 200,000 armed men, the largest such battle Greece had ever seen and a figure comparable with the battles of Waterloo and Gettysburg.

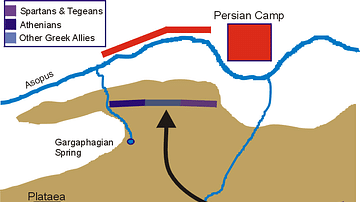

Pausanias was given the command of the combined Greek land forces at Plataea while Leotychidas, the other Spartan king, led the Greek naval force. The Persians were commanded by Mardonius, the son-in-law and nephew of Darius and cousin of Xerxes. As at Marathon in 490 BCE, the Greek heavily-armoured hoplites arranged in a densely packed formation at least eight men deep called the phalanx, where each man carried a heavy round bronze shield and fought the enemy at close quarters using spears and swords, would be a formation which the Persians had no answer for.

In contrast to his later reputation, Herodotus portrays Pausanias as a pious and respectful commander who was able to unite the disparate Greek forces into a successful fighting unit. In addition, after the battle Pausanias, we are told, refused calls for Mardonius' head to be put on a spike as the Persian had so infamously treated Leonidas at Thermopylae. The Greeks had won one of the most important battles in their history, and Pausanias unashamedly claimed his leadership as the principal reason for the victory. According to Thucydides he set up a tripod at Delphi, commemorating the victory with the following inscription:

The Mede defeated, great Pausanias raised

This monument, that Phoebus might be praised

(A History of the Peloponnesian War, 1.132)

There was also a famous poem by Simonides which described the battle and favourably compared Pausanias to the mythical hero Achilles, Greece's greatest ever warrior. Pausanias' reputation was at its very height but from now on the only way was down.

Byzantium & Trials

All the attention and unprecedented limelight in which Pausanias was basking brought an official rebuke from the austere and conservative Spartan authorities but it did not impede the general's career. For, in 478 BCE, he was given command of a Greek fleet of at least 50 ships with which he promptly attacked Cyprus and then took Byzantium on the Bosphorus.

Pausanias' harsh policies soon led to a revolt, though, and a call for aid from Sparta's great rival Athens by the Ionian city-states. At home, too, there were suspicions that he was in cahoots with the Persians, notably releasing prisoners who had been allies to them. There was even talk of letters to the Persian king Xerxes asking for his daughter's hand in marriage (Herodotus makes the more likely claim that the lady in question was the daughter of the satrap Megabates but there is no evidence for either claim).

Commanded to return to Sparta, Pausanias was put on trial for treason. Once again, a successful Spartan general in the wider Greek world had worried the Spartan government into thinking one of their commanders had ambitions to rule all of Greece as a tyrant. Pausanias was, though, acquitted, and so he was able to depart once again for Byzantium where, according to Thucydides, he dressed and ate like a Persian. There he came up against the talented Athenian general Cimon who led the forces of the Delian League and who re-took Byzantium for Athens. Pausanias fled to Colonae in Troad, Asia Minor. Once again, Sparta accused Pausanias of negotiating with the Persians and, c. 471 BCE, he was put on trial a second time only to be acquitted once again for lack of evidence.

Helot Uprising & Death

Pausanias' final brush with Spartan authority came when he was accused of siding with the helots in their revolt against Sparta. Some said that he even promised freedom and full citizenship for the traditional semi-free agricultural workers on which Sparta's economy had so long depended. Enough was enough, and the Spartan rulers called for Pausanias' arrest. Betrayed by one of his servants and seeing the end was nigh, Pausanias sought sanctuary in the sacred temple of Athena Chalkioikos on the acropolis of Sparta. There he was left to ignominiously starve to death. In order not to pollute the sacred ground, Pausanias was removed from the sanctuary just at the point of death. Although not much admired by authority when alive, Pausanias was, under instructions from the Delphic oracle, then given a hero's burial and a joint monument was set up to him and Leonidas where a hero-cult was established.

![The Description of Greece, by Pausanias, Tr. With Notes [By T. Taylor]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/41IggTiktvL._SL160_.jpg)