The Pequot War (1636-1638) was a conflict between the Native American Pequot tribe and the English immigrants who had established settlements in New England between 1620-1630. The immediate cause of the war was the murder of two English traders, Captain John Stone (d. 1634) and John Oldham (l. 1592-1636), allegedly by the Western Niantic tribe, allies of the Pequot.

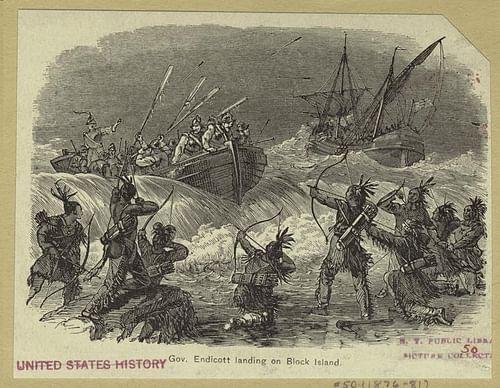

In 1636, the Massachusetts Bay Colony’s third governor, Sir Henry Vane (l. 1613-1662) sent John Endicott (l. c. 1600-1665) on an expedition to Block Island, where Oldham was killed, to demand from the Western Niantic the surrender of the murderers. Endicott wound up burning the native villages there and killing one man before sailing on to a coastal Pequot village, burning it, killing more people, and destroying crops. In retaliation, the Pequots began raiding English settlements and killing colonists.

The conflict escalated, and on 26 May 1637, a company of militia from Massachusetts and Connecticut colonies, assisted by members of the Narragansett and Mohegan tribes, attacked the Pequot stronghold at Mystic. The fort was set on fire and over 700 Pequot, mostly women and children, killed. Survivors fled to another fortification and were led by their chief Sassacus (l. c. 1560-1637) toward safety in New Netherlands (modern-day New York State) where they hoped to find welcome from the Iroquois Confederacy. The Mohawks of the Iroquois instead executed Sassacus, sending his head and hands back to the English.

Of the approximately 3,000 Pequots who lived in the region at the time, only a little over 200 survived the war. Some of these were sold into slavery in the West Indies, Bermuda, or to local farmers while others were given as slaves to the Mohegans and Narragansetts. The Pequots were forbidden to call themselves by their name or inhabit their ancestral lands and, even after the war, bounty was paid by colonial authorities for Pequot scalps.

The war resulted in the near extermination of the Pequot tribe and opened up the regions of Connecticut and Long Island to further English colonization, allowing for easier westward expansion afterwards. Modern historians generally agree that the Pequots were not responsible for the conflict and the causes were fabricated by the English in the interests of expanding and securing profitable ports and routes for trade.

Pequot Tribe & the Dutch

The Pequot tribe lived along the coast of present-day Long Island Sound down through Connecticut and had inhabited the region for thousands of years before the arrival of the Dutch in 1614. European traders had been visiting the area for almost a century by this time and had brought disease the Native Americans had no natural immunity to, resulting in the deaths of a large number of indigenous people along the coast of modern-day Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Maine between c. 1610-1618, but the Pequot, living inland, were unaffected and, by 1614, were already a powerful tribe able to subjugate others such as the Niantic, Nipmuc, and Mattabesic.

In 1622, the Dutch established a trading post on the Connecticut River near modern-day Hartford and welcomed trade with all the indigenous tribes of the region, but the Pequot, who were by this time even more powerful, subdued the Narragansett, and cornered the market, forbidding others from trading with the Dutch. When the Massabesic refused to comply, the Pequot killed a number of them on their way to the trading post. The head of the trading post, Jacob Elekens, retaliated by taking the Pequot chief Tatobem hostage and holding him for ransom. He demanded a large payment for the chief’s safe return as well as the promise that the Pequot would allow peaceful trade between the Dutch and all the tribes of the region.

The prized commodity for the Dutch was fur, and this is what Elekens expected in return for Tatobem; instead, he received between 140-280 yards (128-256 m) of tightly strung, highly polished shells. Believing the Pequots were mocking him, he had Tatobem killed and delivered his corpse to the Pequot who retaliated by burning the trading post. The Dutch quickly responded with a gesture of peace – fearing loss of trade – by replacing Elekens with one Pieter Barensten who spoke the Algonquin language. In the course of the peace negotiations, Barensten came to understand the polished bead belts were known as wampum which was highly prized among the indigenous people. Scholar Susanah Shaw Romney comments:

At once a powerful diplomatic symbol and a valued trade good, wampum provided the basis for Long Islanders’ exchange with inland groups who used it for sacred ritual purposes. Dutch traders quickly adapted to local uses of wampum and came to regard it first as a trade item that afforded access to furs and later as a form of currency in exchanges with colonists and native villagers alike, from Long Island to the Delaware Valley. (133)

Barensten, recognizing the value of wampum, freely gave the Pequot a monopoly on trade with the Dutch and the Pequot had their tributary tribes begin manufacturing wampum in bulk. The wampum was traded with the Dutch who then traded the wampum with the tribes of the Iroquois Confederacy for fur. The Pequot received highly prized Dutch goods such as iron pots, weapons, and tools, among other commodities.

Arrival & Expansion of the English

In 1620, Plymouth Colony was established on the coast of Massachusetts and, owing entirely to the assistance of the tribes of the Wampanoag Confederacy, was flourishing by 1622. The success of Plymouth encouraged the arrival of more immigrants and the establishment of other colonies over the next eight years until, in 1630, John Winthrop (l. c. 1588-1649) arrived with 700 Puritan colonists to expand upon and develop the Massachusetts Bay Colony, founded in 1628 by John Endicott, the first governor. Winthrop took over as governor and spread the colony out further than Endicott had initially.

Plymouth Colony had already had difficulties with the Dutch concerning trade with the natives and had signed a 1627 treaty dividing territories and tribes between them. Winthrop either had no knowledge of this treaty or ignored it and, in 1633, constructed a trading post on the Connecticut River at Windsor, upstream from the Dutch trading post, where it could intercept fur. The Dutch responded by establishing their own trading post further upstream, a fortified settlement known as House of Good Hope, which was protected from any threat from the English by the Pequot under Sassacus, son of Tatobem, the new chief.

Initial Conflict

The Pequot could not be everywhere, however, and some of their tributaries began trading with the English downstream where they could get better prices and snub their overlords at the same time. The divisions the trade with the Europeans caused put increasing strain on the Pequot alliances, and the Mohegans, who had been part of the Pequot tribe, broke away and aligned themselves with the English who, they felt, treated them with greater respect and were fairer in trade than the Dutch. The alliance of the Mohegans with the English shifted wampum production and trade power from the Pequot and Dutch to the Mohegan, English, and, shortly after, the Narragansett.

The English actually had little regard for the natives except as a means to an end in trade and no regard for the Dutch. An English tract from 1637 begins, "New England (a name now every day more famous) is so called because the English were the first discoverers, and are now the planters thereof" (Orr, 67). The Dutch, who had arrived in North America first, were expected by the English to remain in their territories to the south in the region the natives called Manhatance and the Dutch had renamed New Netherlands. Conflicts between the English and Dutch increased until, in 1634, the English Captain John Stone and seven of his men were killed, allegedly by Niantics.

When confronted by the English, the Niantics claimed they thought Stone was Dutch and had justly killed him in retaliation for his killing of one of their own. To keep the peace, Sassacus sent the English a quantity of wampum. In 1636, the English trader John Oldham was killed, and this was also blamed on the Niantics. Both were most likely killed by Narragansetts who were overlooked by the English because they were allies and profitable in the production and trade of wampum for fur.

Stone was a pirate and slaver, and the news of his death was actually received with some relief by the colonists, while Oldham was a troublemaker who had been banished by the Plymouth Colony and was at odds with some of the magistrates of Massachusetts Bay. Their deaths, however, provided Massachusetts Bay Colony with an excuse to drive the Pequot from their lands so the English could control trade there and keep the region out of the hands of the Dutch.

Sir Henry Vane, who had replaced Winthrop as governor in May of 1636, sent Endicott to Block Island, where Oldham had been killed, to demand the surrender of his murderers. The Niantic at first welcomed them, believing they were traders, but Endicott’s heavily armed men made them wary. When they refused his demands of wampum, Pequot children to be held as hostages, and the surrender of the murderers, Endicott attacked, and the natives fled into the interior of the island. Endicott then burned two villages and left to do the same at a Pequot village downriver. Violence had not been authorized, and Vane was not pleased, knowing that Endicott’s action would no doubt draw quick retaliation; he was right, and the Pequot War had begun.

Pequot War & Mystic Massacre

The war was actually a series of raids on colonial settlements in the fall and winter of 1636 through the spring of 1637 in which bands of Pequots would fall upon the colonists, killing them and their livestock and burning their homes, and then disappear back into the wilderness. There was no formal engagement between opposing forces throughout 1636 and into the spring of 1637. Vane had lost the election of May 1637 to Winthrop who was again governor and ordered defensive measures, but it was difficult to defend against an enemy one could not see and had no way of detecting until it was too late.

Winthrop wrote to William Bradford (l. 1590-1657), governor of Plymouth Colony, asking if he could count on his assistance, and Bradford complied. At about the same time, the Pequot were trying to enlist the Narragansett in their cause, arguing that, if the Narragansett helped the English against them, they would only be opening the way for their own certain destruction and future enslavement. If the Narragansett sided with the Pequot against the English, however, they could wage an effective war, striking the colonists suddenly from all sides without warning, until the English were driven from the land or completely eliminated.

The Narragansetts seem to have been considering this proposal seriously but their minds were changed by Roger Williams (l. c. 1603-1683), an exile from the Massachusetts Bay Colony who had lived among the Wampanoag and Narragansett, purchasing land for his Providence Colony from them. Williams suggested that the Narragansett would profit far more from an alliance with the English who would help them destroy their old rivals and open up Pequot territory for Narragansett trade. Williams was already on good terms with the two Narragansett chiefs Canonicus (l. c. 1565-1647) and Miantonomoh (l. c. 1600-1643) and they trusted him more than they did Sassacus and so sided with the English.

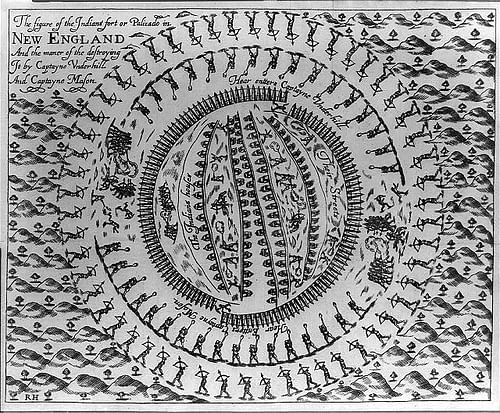

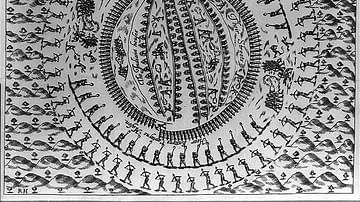

The Narragansett’s choice decided the outcome of the Pequot War and the later history of the region because, if they had accepted the Pequots' proposal, they probably would have been able to drive out the English. Instead, in May 1637, they helped guide the colonial militias under captains John Underhill (l. 1597-1672) of Massachusetts Bay and John Mason (l. c. 1600-1672) of Connecticut Colony to the Pequot fortress at Mystic, Connecticut. The English-Narragansett force arrived before dawn on 26 May 1637 and set fire to the palisades after breaking in the front gate and shooting whomever they found inside. The fort was surrounded, so those who tried to escape the flames were shot dead outside. Since most of the warriors were away at another site with Sassacus, the “great victory” Mason and Underhill became famous for was the massacre of over 700 people, mostly women and children, panicked by musket fire and blinded by smoke.

Scholar David J. Silverman comments on how Winthrop’s response to the Mystic Massacre was celebratory as "the Massachusetts Bay Colony memorialized the victory by declaring a public day of thanksgiving after its soldiers returned home safely" (224). The militia suffered only 26 injured and two killed in the action. Winthrop’s proclamation (frequently, and wrongly, attributed to Bradford of Plymouth Colony) is often cited today in Native American protests against Thanksgiving Day.

Aftermath

The Pequots who escaped alerted the further fort, and warriors retaliated by attacking the militia and their march back home. There were too few to mount a serious engagement, however, and Sassacus decided to lead his people south and seek help from the Mohawks around Manhatance. They were pursued by John Mason and his Mohegan ally Uncas who, in mid-June, engaged them in a swamp near modern-day Fairfield, Connecticut. Sassacus and a number of his warriors escaped after the English-Mohegan militia allowed the surrender of women and children.

When Sassacus arrived in Manhatance, however, he was almost instantly executed by the Mohawks and his head and hands sent to the English in a gesture of friendship. His followers returned home or remained in the region of New Netherlands and were absorbed into other tribes. The Treaty of Hartford, signed between the English, the Narragansett, and the Mohegan on 21 September 1638, divided the spoils of war. The 200 Pequots who survived the conflict were dispersed; some either sold into slavery in the West Indies or Bermuda or to local landowners.

Many were given as slaves to the Mohegan and Narragansett and were treated so poorly, especially by the Mohegan, that the colonists finally reclaimed them out of pity. Many Pequots were absorbed into other New England tribes as they were forbidden to return to their ancestral lands or call themselves by the name Pequot and their former territory was divided between the three victorious parties, with the English taking the profitable riverfront locations.

Conclusion

The Pequots who were finally reclaimed by the colonists came to be known as Mashantucket Pequots and were given land at Noank in 1651 which was taken from them in 1666 when they were relocated to Mashantucket. By 1774, there were only 151 Pequots on the reservation, and by 1800, there were less than 40. Pequots who converted to Christianity became part of the Brotherton Movement and joined that community and demands from the Americans for more land reduced the 1,000 acres (c. 400 ha) of the reservation to 213 acres (86 ha) by 1856.

It was not until the 1970s that the Pequot had the strength to sue the State of Connecticut for the illegal land sales of 1856 and not until 1983 that their reservation was restored to its 1,250 acres (c. 500 ha) They also received recognition from the US government at the same time along with federal aid which they invested carefully and, with the profits, established Foxwoods Resort, the largest gambling casino in the United States at that time, which drew many of the tribe back to their original lands. Since then, efforts have been ongoing to revive the Pequot language and culture.

Most modern-day scholars agree that the causes of the Pequot War were largely manufactured by the English to expand their reach inland and remove the Dutch from New England trade. Scholar John Wilson, for example, writes, "the supposed offenses of the Pequots (some of which had occurred years before and had not, in fact, been committed by Pequots) were little more than a pretext" (89). Once the Pequots were removed, the Dutch withdrew from the Connecticut region and the English had a monopoly on the fur and wampum trade.

The prediction of the Pequots to the Narragansetts proved true forty years later after the English won King’s Philip’s War (1675-1678) against a coalition of tribes organized by Metacomet (also known as King Philip, l. 1638-1676) of the Wampanoag Confederacy. The Narragansetts had remained neutral during the conflict but had agreed to take in native refugees. The colonists accused them of helping the enemy and attacked the Narragansetts in 1675, setting fire to their fort and burning their women and children just as they had those of the Pequots.

The Narragansetts rallied and fought back, but it was too late now as the immigrants by this time outnumbered the indigenous tribes and had already taken their lands and livelihood, as they would continue to do from the east to the west coast. The Pequot War established the model the English colonists would adhere to from 1637 onward. Afterwards, they would claim they represented the "land of the free and the home of the brave", but this designation ignored those they took that land from and their descendants continue to do so right up to the present day.