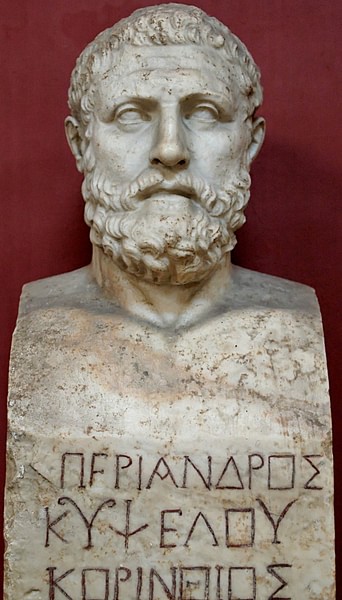

Periander was the second tyrant of Corinth (d. c. 587 BCE); Diogenes Laertius only mentions that he was eighty when he died, meaning that he was probably born c. 667 BCE. His father Cypselus (r. 657-627 BCE), from whom the short-lived Cypselid dynasty takes its name, was the first tyrant of Corinth.

He married Lysida, the daughter of Procles (the tyrant of Epidaurus) and Eristheneia (the daughter of Aristocrates and sister of Aristodemus, who were the joint tyrants of Arcadia), whom he personally called Melissa. They had three children: Cypselus (their eldest son named after his grandfather), Lycophron (their second son), and it seems that they also had a daughter, but Herodotus does not give her a name. Two stories survive concerning the death of Melissa; one claims that she was pregnant when Periander killed her by kicking her in her stomach, the other claims that he threw a stool at her, resulting in her death.

EARLIER LIFE

Periander took control of Corinth upon the death of his father. In that bizarre mix of divine intervention and mortal motivation that was early Greek history, it could hardly have happened any other way, for Periander's father had received a Delphic oracle that read:

That man is fortunate who steps into my house,

Cypselus, son of Eetion, the king of noble Corinth,

He himself and his children, but not the sons of his sons.(Hdt. 5.92E)

Periander was one of those children. Another story, probably dating to the earlier part of Periander's rule, involves Arion the musician. Arion was a famous travelling musician who frequented Corinth and established dithyrambic performances there (a kind of choral dance). The thriving musical culture of Corinth at this time (as captured by Periander's patronage of Arion), as well as its booming pottery industry and the city's cordial relationships with Alyattes of Sardis and Thrasybulus of Miletus, all highlight the great material prosperity of Corinth during Periander's rule, an aspect of his rule on which Herodotus did not clearly elaborate. Herodotus instead seems to divide Periander's rule into two parts:

Periander was to begin with milder than his father, but after he had held converse by messenger with Thrasybulus the tyrant of Miletus, he became much more bloodthirsty than Cypselus. (Hdt. 5.92F)

But what was this message, and why did it corrupt Periander's goodwill?

Thrasybulus' MESSAGE

The message that Periander received was in a response to a question he had asked Thrasybulus concerning how best to maintain the Corinthian tyranny. The story goes that Thrasybulus led Periander's messenger into a cornfield outside the city of Miletus, and started reaping the tallest and best of the crop, throwing it away. The messenger returned to Corinth confused and disturbed. He relayed what he had seen to Periander, describing Thrasybulus as "a madman and destroyer of his own possessions" (Hdt. 5.92F). However, Periander understood the meaning of Thrasybulus' actions: in order for Periander to maintain his rule, he must dispose of those Corinthians who were the most outstanding of citizens, thus decimating the influence and ability of any dissidents to challenge his rule.

This story is retold twice by Aristotle, however, in his version, it is Thrasybulus who sends a messenger to Periander, and Periander who cuts down the corn. Aristotle views this story and its consequences from a political viewpoint, commenting:

this policy is advantageous not only for tyrants, nor is it only tyrants that use it, but the same is the case with oligarchies and democracies as well; for ostracism has in a way the same effect as docking off the outstanding men by exile. (Pol. 3.1284a)

PERIANDER'S LUST FOR WEALTH

One of the main narratives about Periander is preserved in the speech given to the Corinthian Seocles. Seocles uses the example of the Cypselid tyrants to warn the Peloponnesians against allowing Sparta to reinstate the tyrant Hippias in Athens - such is the nature of tyranny. The final part of his story concerns Periander's hunt for buried treasure, the oracle of the dead, ghostly apparitions, necrophilia, and the public humiliation of the Corinthian female population.

Periander had sent messengers to the Oracle of the Dead at the river Acheron in Thesprotia to find out where a dead friend had hidden his treasure. Instead of a receiving a location, the messengers were astonished by the ghost of Melissa, who told them that she would never reveal the location of the treasure because she had received an ungracious and improper burial. Her ghost was cold and naked because Periander had not burned her clothes but buried them with her corpse, where they were or no use to her ghostly self. In order to prove the validity of her spectral utterance, Melissa told the messengers that "Periander had put his loaves into a cold oven" (Hdt. 5.92G).

When Periander received this message, he knew it to be true, for only the ghost of his dead wife could have known that he had defiled her corpse by committing necrophilia. In response to this message, and in order to appease his dead wife and find the location of the lost treasure, Periander gathered all of the Corinthian women at the temple of Hera. There he stripped them all of their clothes, casting their garments into a pit. Periander then burned the clothes while in prayer to Melissa. Upon this, he sent messengers to the oracle again, and having appeased Melissa, was told the location of the buried treasure. However, we are not told the importance of this treasure, or indeed whose exactly it was.

Later Life

Herodotus is our main ancient source for the narrative of Periander's rule, especially his later rule. The story goes that Lycophron, once he had learned that his father had killed his mother (his grandfather Procles had told him), completely ignored Periander's pleas for reconciliation. The feud grew to such a level that Periander enacted a law that no one should harbour or speak with his son. This law was put to the test when on the fourth day of its passing Periander came across his son, dishevelled, dejected, and demeaned. Unable to abide by his own law, seeing the effect it had had on his son, Periander approached his son and tried again to reconcile. Lycophron's response to this was to chastise his father for breaking his own laws, and to reject outright such reconciliation (Periander had murdered his mother after all)! As a result of this, Periander shipped Lycophron off to the island of Corcyra (a colony of Corinth under Periander's control at this time), so that he could live apart from his father. Because Periander regarded Procles as the instigator of such troubles, in as much as he had told his son that he had murdered his mother Melissa, he then invaded Epidaurus and imprisoned Procles.

As Periander grew old, he reflected that he needed to secure a successor. Cypselus (Periander's oldest son) was seen to be too dim-witted to become tyrant, so Periander realised that he needed to reconcile with Lycophron in order to maintain his dynasty. After much negotiation (Periander had sent Lycophron's sister to persuade him to return, but this had failed), Lycophron agreed to return to Corinth on the condition that Periander lived out the rest of his life on Corcyra. The Corcyrans however, on hearing this, killed Lycophron, so that Periander would not come to Corcyra, presumably because they feared or loathed his tyrannical nature.

On hearing the news of Lycophron's death, Periander was overcome with anger and rage, and supposedly sent 300 Corcyran men to be castrated at by Lydian King, Alyattes, at Sardis, so that the Corcyrans might feel the same pain that he had in losing his family line (the Samians intervened to prevent this).Having failed to secure his son as successor to the Corinthian tyranny, Periander was succeeded by his nephew, Psammetichus, who would be the last Cypselid tyrant of Corinth, thus fulfilling the Delphic oracle which had prophesied the Cypselid tyranny.

DEATH

Diogenes Laertius preserves a peculiar story concerning how Periander actually died, and it is one of many stories about Periander more generally whose actual historicity can be considered doubtful. In this case, one might wonder who was left alive to know of Periander's original intentions:

There is a story that he [Periander] did not wish the place where he was buried to be known, and to that end contrived the following device. He ordered two young men to go out at night by a certain road which he pointed out to them; they were to kill the man they met and bury him. He afterwards ordered four more to go in pursuit of the two, kill them and bury them; again, he dispatched a larger number in pursuit of the four. Having taken these measures, he himself encountered the first pair and was slain. (DL. 1.7.96)

PERIANDER'S LEGACY

Periander was remembered as a prototypically cruel tyrant. Whether or not Herodotus himself held this view, that was certainly how the tyrant was viewed by the character Seocles, who, after having told the story of Periander, finishing with the story of the treasure and burning of clothes, says:

This, then, Lacedaimonians, is the nature of tyranny, and such are its deeds. We Corinthians marvelled greatly when we saw that you were sending for Hippias, and now we marvel yet more at your words to us. We entreat you earnestly in the name of the gods of Hellas not to establish tyranny in the cities, but if you do not cease from so doing and unrighteously attempt to bring Hippias back, be assured that you are proceeding without the Corinthians' consent. (Hdt. 5.92G)

Further, Plato mentions Periander in the same breath as that most tyrannical of rulers, Xerxes:

"Do you know," said I, "to whom I think the saying belongs—this statement that it is just to benefit friends and harm enemies?" "To whom?" he said. "I think it was the saying of Periander or Perdiccas or Xerxes or Ismenias the Theban or some other rich man who had great power in his own conceit." (Plato, Rep. 1.336a)

Nevertheless, different interpretations exist. Some of the views presented by the 3rd-century CE Diogenes Laertius (while many of them may be considered spurious, such as Periander's letters) show that a more complex characterisation of the Corinthian tyrant had developed, associating the tyrant as a Wise Man, and crediting him with writing a 2,000-word didactic poem. Additionally, Diogenes preserves the text to an epitaph supposedly inscribed on a cenotaph set up by the Corinthian people for Periander:

In mother earth here Periander lies,

The prince of sea-girt Corinth rich and wise.

My own epitaph on him is:

Grieve not because thou hast not gained thine end,

But take with gladness all the gods may send;

Be warned by Periander's fate, who died

Of grief that one desire should be denied.(DL,1.7.97)

Nevertheless, even then, the majority of the views preserved in Diogenes' account conform to a stereotypical view of depraved tyranny, even including an accusation of incest. All of these varied accounts serve to show that there is a problem in recreating a 'historical' Periander. Herodotus wrote in the 5th century BCE, some 150 years after Periander's rule, and Aristotle was born almost 200 years after the death of Periander. In this time, oral histories would have been embellished, and the exact narrative of certain stories confused, highlighted by the character reversal that had already taken place between Herodotus and Aristotle's accounts of the cornfield message. In this regard, such stories are perhaps more important for our understanding of how their authors regarded tyranny within their own lifetimes, rather than how Periander actually ruled over 6th-century Corinth.

![Ectypon Utriusque Fortunae Sive Periander Corinthi Rex: ... in Scena Exhibitus a Musis Benedictinis Episcopal. Lycei Frising. Die II. Et IV. ... 1761]... (English and German Edition)](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51He2HkShnL._SL160_.jpg)