Persian miniature painting is a courtly and aristocratic art, with exquisite colors, balanced compositions, and meticulous attention to detail. Although its origins can be difficult to trace, many consider the Arzhang, the illustrated book of prophet Mani (founder of Manichaeism and himself also an artist) from the 3rd century CE during the Sassanian Empire as the foundation of Persian schools of painting.

Throughout its history, Persian miniature painting has had a close affinity with the royal courts and its progression and development had a close connection to the royal patronage and the degree to which the rulers and their regional governors supported and encouraged the artists. Aside from the capitals in each period, certain regions and cities also witnessed and welcomed the appearance of different schools of painting, some of the best-known of them being Tabriz, Shiraz, and Herat.

Although each school had its own characteristics which would make it distinct from the others, such as the choice of color palette or the proportions of human figures, all shared some similar stylistic features such as the depiction of faces from the three-quarter view, absence of perspectival depth, and the use of various angles in picturing the elements within a single painting. Furthermore, the Persian miniature paintings have experienced various influences from the Chinese and, later in the 18th and 19th centuries, from European paintings. Nevertheless, it has always managed to keep its Persian identity and essence.

Subject Matter & Characteristics

There are numerous characteristics, both visual and symbolic, that set Persian paintings apart from their Eastern counterparts, and these qualities reflect the artistic and philosophical views of Persian artists. The common belief among scholars is that during the late 14th and 15th centuries, Persian painting was reaching its pinnacle and, according to Arthur Upham Pope, it was during these two centuries that a definitive style of Persian painting was taking form. He notes:

The entire composition is in a single plane. There are no successive curtains of diminishing light, no converging perspectives that break through the surface. The figures are encompassed by no atmosphere and cast no shadows. Neither the individual figure nor the colors blend or merge and modeling, save for the shallowest and most delicate kind, is studiously avoided. (107)

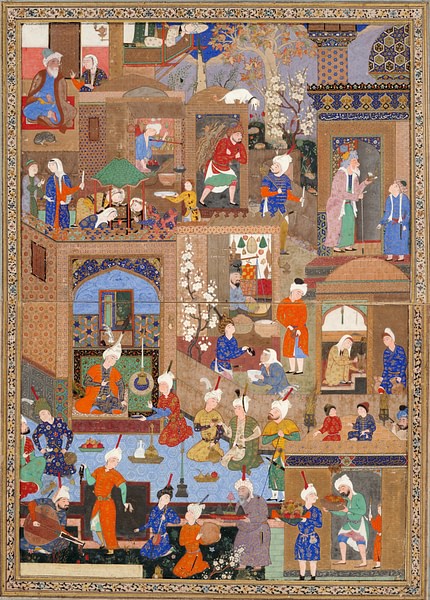

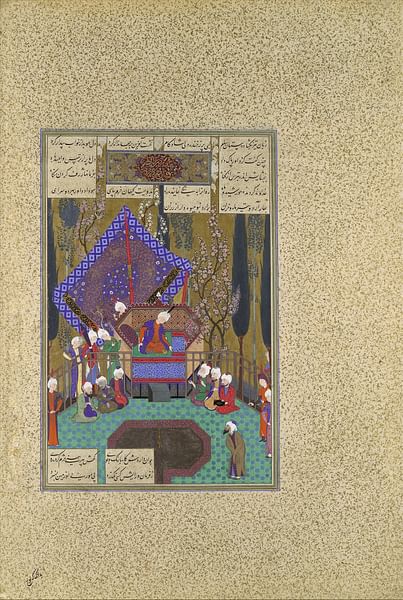

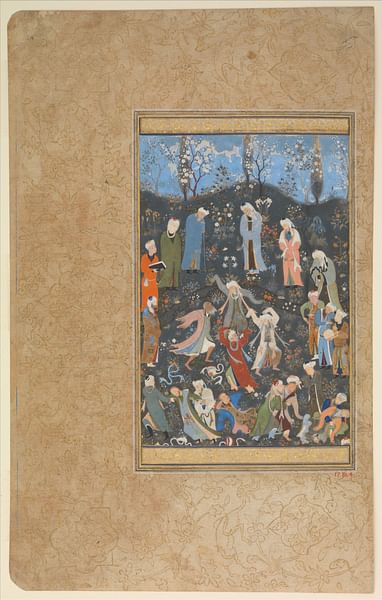

Partly due to the influence of Sufism and their system of thought, Persian miniatures are free of any particular space or time which endows them with a transcendental quality. Even if elements such as the moon, stars, or even the sun are depicted in the sky, marking it as day or night, they have no particular effect on the rest of the painting since there is no play of light and shadow in the composition. In some examples through the use of a separate frame (with a different sky color and vegetation) inside the composition, the Persian painter has even managed to create two simultaneous timelines. Moreover, as mentioned, Persian miniatures lack perspectival depth. Instead, everything within the composition moves upwards and is pictured in layers rather than diminishing in size and appearing to move inwards.

Before the prevalent influence of European art, the clothing of the figures in the Persian miniatures was almost the same in nearly all periods. Covered with rich plain colors and at times decorated with delicate motifs, both male and female characters dress nearly the same, which at times makes it difficult to tell them apart. Headdresses are one of the specifications that help the viewer in distinguishing the two. While women usually wear delicate scarfs and ornate crowns, men wear different hats from the skins of the animals and different turbans. For men, the style of the headdress can usually also help with identifying the period to which the painting belongs. For example, the Safavids which are also known as the "Red Heads" can be identified with the red rod that is placed above their turban caps.

Another interesting point concerning the figures in these paintings is the angle from which their body parts are depicted. In painting the hands, the thumbs are usually at a distance from the rest of the fingers and the hand in its totality has a delicate dance-like movement to it. The feet are also mostly depicted in profile view. Moreover, within the composition as a whole, one can see that each element (be it architecture, vegetation, or gardens) is depicted using various viewpoints and angles. This reminds one of Egyptian art and their depiction of the human figure and other pictorial elements each from their perfect angle.

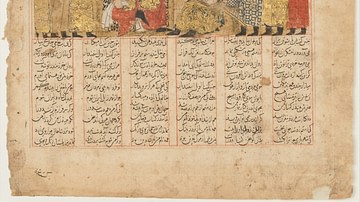

From the point of subject matter, Persian miniature paintings mostly depict scenes of royal huntings, battle scenes, and most importantly Persian mythology and poetry; specifically stories of Shahnameh (The Persian Book of Kings) of Ferdowsi (c. 940-1020). Among some of the most illustrated stories of Persian literature are the Seven Labors of Rustam, Yusuf and Zulaikha, Khosrow and Shirin, and Leyla and Majnun. From the reign of Shah Abbas the Great (r. 1588-1629) of the Safavid Dynasty onward, we can see a notable increase in the influence of European art on Persian paintings which would be experienced not only in the emergence of new subject matters such as genre paintings, half-nude figures, and solo paintings of birds and plants among many other examples but also in the use of light and shadow and a change in the attire of the figures.

Technique & Material

To gain the ability to create any visual form from memory and with precision, the amateur Persian painter had to study and practice copying works of the masters for years before attempting to execute a painting on his own. It is worth mentioning that even the masters themselves would occasionally copy certain parts of their work to save time. The process of copying was done using a pounce. At first, a very thin animal skin was pierced with a fine needle, tracing the lines of the painting underneath it. After the process of piercing was finished, the painting was replaced with blank paper and charcoal powder was passed over the pierced sheet. The charcoal passed through the holes and left a trace of the copied work on the blank paper, after which the painter proceeded with additional coloring and detailing.

Although paper itself was invented in China in 105 CE, it was centuries later and in the middle of the 8th century that the Persians started using it instead of parchment and papyrus. To create the fine lines that are characteristic of Persian miniatures, hair from the tail of squirrels and Persian cats were used to make brushes of different thickness, and to create the vivid and rich colors that were used within the paintings, pigments were made from both organic and nonorganic sources and minerals. Unfortunately through time, some of these colors were prone to damage and discoloration and thus have lost their richness.

Although in later centuries single-page paintings became more common, illustrated books were favorable for the nobles and royal court. The production of such masterpieces required a whole team of miniature painters, scribes, binders, gilders, etc., all of whom worked together in a royal atelier or library under the supervision of a director.

Famous Artists

Throughout the history of Persian painting, there have been numerous artists who have attributed to the many unique characteristics and qualities of Persian miniatures. One of the best-known Persian miniature artists of all time is Kamāl al-Dīn Bihzād (c. 1450- 1535). As an orphan, he was trained by the skilled miniature painter, Mirak Naqqash but soon went on to develop his own unique style which would mark an apogee in Persian painting. Under the skilled and delicate brush of Bihzād, Persian painting found life and movement, lost much of its stiffness and formality, and was injected with a degree of realism and drama. Bihzād shifted the subject of the paintings towards everyday life and created almost genre-like paintings in which figures moved freely. Having the patronage of four different rulers from the late 15th century into the early 16th century, the Safavid era, Bihzād not only directed the royal libraries and ateliers but also had a great number of students and followers who imitated his style of painting. This would later create an issue for the scholars and researchers in identifying the works which could genuinely be attributed to the artist himself.

Another well-known and skilled miniature artist was Aqa Riza (c. 1565- 1635), also known as Riza-yi ‘Abbasi. Having enjoyed the patronage of Shah Abbas the Great, he was granted the title of "Abbasi" in the early 17th century. Although he spent a few years of his life away from the royal court and the artistic world and occupied himself with lowly activities, throughout his career, Aqa Riza was "one of the most innovative figures of the age and because of his stylistic developments during his career was even thought to have been two different people" (Canby, 98). Aside from utilizing new subjects such as semi-nude women and contemplative sheiks and dervishes, he also had an innovative approach towards painting techniques. In describing a drawing of Aqa Riza which is illustrative of his earlier style and may have falsely been attributed to Bihzād, Sheila Canby notes:

He has chosen to depict a moment of high drama and has not shied away from showing man’s anxiety… To heighten the sense of movement, Riza has employed a line of varying thicknesses, which some scholars believe he, and not Sadiqi Beg, introduced to Persian draughtmanship. (Canby, 98)

A well-known artist of the 16th century is Sultān Muhammad who was active in the school of Tabriz and was not only influenced by the works of Bihzād but also the Turkmen school of painting. Not much is known about his life, but that he worked in the atelier of Shah Ismail I (r. 1501-1524) and that he had many pupils, among whom was Tahmaps I. Besides those mentioned here by name, there were many talented artists who worked both independently and in the royal courts and ateliers that produced some of the most exquisite and detailed works of art.

Later Influences

Persian miniature paintings have maintained their charm and appeal and with their many unique characteristics, these paintings were and continue to be a source of inspiration for not only contemporary Persian artists but also Western artists such as Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944), Paul Gauguin (1848-1903), and Henri Matisse (1869-1954). One can discern in the works of these artists traces of the vivid and rich colors, patterns, compositions, and lack of perspectival depth seen in Persian paintings.