Phocion (c. 402 – 318 BCE) was an Athenian statesman and military commander who, according to tradition, was made a general a staggering 45 times. A student of Plato and known as 'the Good', his political position was somewhat ambiguous, and ultimately he was accused of colluding with the Macedonians and dismantling the democracy of Athens. He is the subject of one of Plutarch's Lives biographies.

Early Life & Career

Phocion (also spelt Phokion) was born in the deme of Potamioi; his father was Phokos. Not much is known of his early life except that he studied at Plato's Academy and became a follower of the great philosopher. Amongst his friends he counted the philosopher Xenocrates and the noted general Chabrias. This distinguished company may explain Phocion's reputation as a highly principled and conservative member of the Athenian elite and his popular title of 'Phocion the Good' (ho chrestos). He was also famous for his austere lifestyle, and he once sent his son Phocus to Sparta so that he might benefit from their less ostentatious lifestyle compared to the aristocracy of Athens.

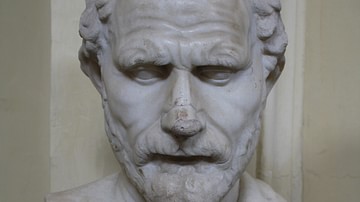

Phocion consistently opposed the policies of his contemporary, the famed orator Demosthenes and preferred a more pacifist policy towards the increasingly threatening Macedon. Plutarch informs us that he never sought office but accepted his duty when he was called upon. The same could be said for his policies – he would often speak his mind but bend to the decision of the government. As Plutarch quotes him, "you can make me act against my wishes, but you shall never make me speak against my judgement" (225).

According to Plutarch, Phocion fought with distinction at the sea battle off rebellious Naxos in 376 BCE. His first military role, collaborated by other sources, was in 349 BCE when he was general (strategos) for the campaign in Euboea. This was followed by action on Cyprus, although perhaps not as a commander. Plutarch also notes in his biography that it should be remembered that by the time Phocion gained a position of power and influence, whatever he may have been accused of in his later career, the ship of state was already a wreck. Athens found itself in a period of long decline from which it would never manage to extract itself.

Strategos & Chaeronea

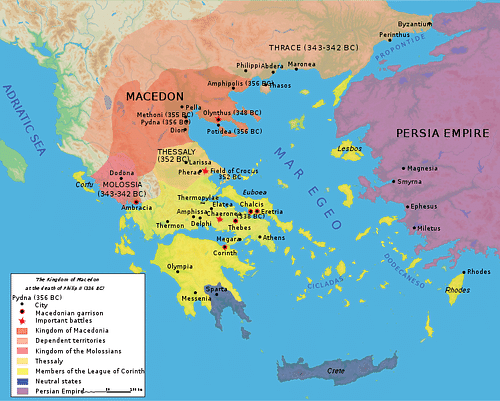

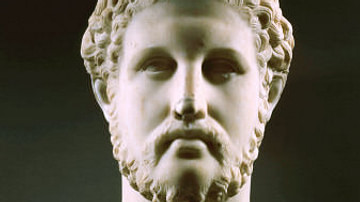

Famously credited with being made a strategos an impressive 45 times by ancient writers, if true, this would make Phocion the most honoured commander in Greek history. He was given the title again in 343 BCE (for the campaign in Megara) and then followed a string of appointments. In 341 BCE he was general in Euboea again and in 340 BCE at Byzantium where he defeated Philip, capturing some of his ships and demonstrating that the great Macedonian general was not invincible after all. He commanded in 339 BCE, and again in 338 BCE and 335 BCE, the latter two illustrate Phocion's increased political stature in the aftermath of the Battle of Chaeronea (338 BCE) in which he did not participate as general, probably because of his stance not to fight the Macedonians in a battle he believed Athens could not win. In one of the most significant battles in Greek history, a combined Athenian and Theban force was defeated by Philip II of Macedon and Athenian regional dominance was permanently ended.

Phocion, made a member of the Athenian Council (bouleutes) in 336 BCE, was prominent in the negotiations which achieved preferential treatment for Athens amongst the Greek defeated city-states. In 335 BCE, when Alexander the Great demanded the troublesome orators Demosthenes, Lycurgus, and Hyperides be given up, Phocion recommended to the Athenians compliance and cited the example of Thebes which had invoked Alexander's wrath and been completely destroyed as a consequence. Plutarch credits him with later successfully negotiating an amnesty, but later historians suggest this was in fact achieved by Demades.

Appeasing Macedon

Phocion was once again made strategos, this time for four consecutive appointments from 322 BCE to 319 BCE. The first of these was during the Lamian War in Thessaly, which he had publicly opposed, between Macedon led by Alexander's successor Antipater and a combined Greek force led by Athens. Antipater won victory at Crannon and, once more, Phocion took on the role of negotiator. The result was Antipater established a garrison at nearby Munichia and Athens' constitution was amended to reduce the city's political base, in effect creating an oligarchy to replace the previous system of democracy. Phocion, considered too friendly with key Macedonians and too sympathetic to their demands, was blamed for this capitulation. In addition, Phocion helped Nicanor (the Macedonian garrison commander), or rather, considering him trustworthy he did nothing to prevent his takeover of Athens' port, the Piraeus. When Polyperchon oversaw a democratic uprising in 318 BCE, Phocion was charged with treason and condemned to death by poison as a result.

In later years Phocion's reputation would be somewhat restored, especially following the work of Demetrius of Phaleron, the Athenian statesman, and later historian and librarian at Alexandria. Phocion would thus become known as the last Athenian statesman of great stature and achievement, a man of honour and principle, who later writers such as Plutarch lamented as a victim of turbulent and treacherous times.