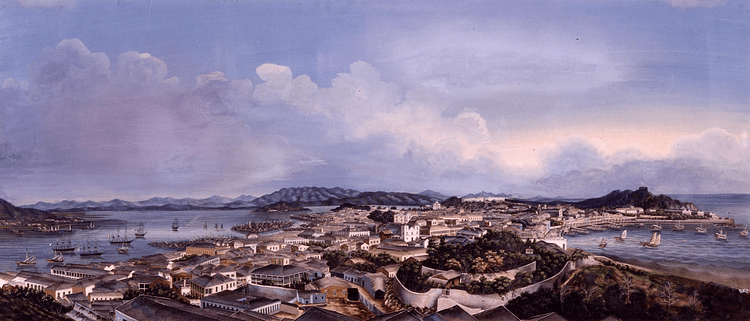

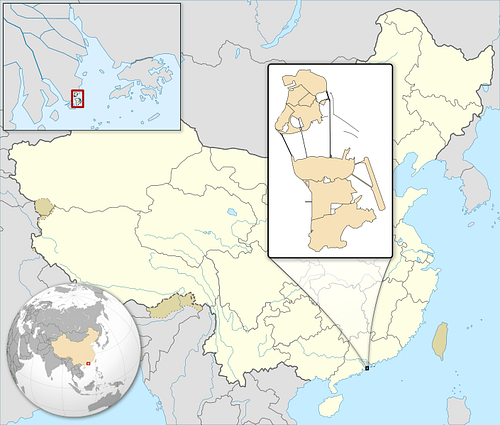

Macao (Macau) is located on a peninsula in the estuary of the Pearl River delta in southeast China and it was a Portuguese colonial settlement from c. 1557 until 1999. Macao was a major trade hub of the Portuguese Empire and with its unique access to the Chinese market, was able to supply the Chinese with silver, pepper, and sandalwood.

Crucially, Macao traders were given access to the major Chinese silk fairs and so took away with them silk and other goods in high demand in both Asia and Europe such as Ming porcelain, musk, and gold. The settlement was at its peak from the mid-16th to mid-17th century, after which it faced stiff competition from other European traders, notably the Dutch and British. Like its neighbour Hong Kong, Macao was handed back to the Chinese in 1999 and became a special administrative region of the People's Republic of China.

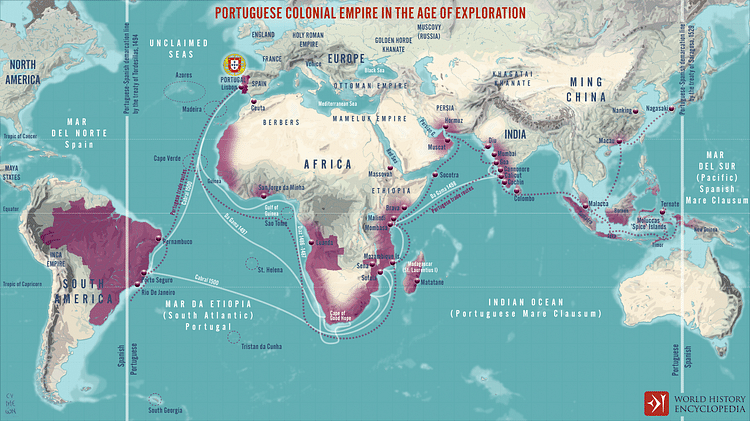

The Portuguese Empire

Ever since 1497-9, when Vasco da Gama (c. 1469-1524) had sailed around the Cape of Good Hope and shown the possibilities of a maritime route between Europe and Asia, the Portuguese had been busy building an empire. Portuguese Cochin was founded in 1503 and Portuguese Goa was established in 1510. Malacca in Malaysia was taken over in 1511. The Portuguese sailed relentlessly eastwards and in 1517 a fleet departed from Malacca to reach the Chinese city of Guangzhou, more familiar to Europeans by the name the Portuguese gave it: Canton. This foray into Chinese affairs got off to an inauspicious start when two of the Portuguese ships were sunk and the envoys were executed. The Chinese, then ruled by the isolationist Ming Dynasty (1368 to 1644), considered these odd visitors cannibals and were highly suspicious of letting them in on their East Asian trade network. The Chinese were not impressed either with the Portuguese firing off cannons, building a fort without permission, and making various other diplomatic blunders.

Establishing Macao

The Portuguese were undeterred, and they eventually negotiated a deal with the Chinese. Precisely how this was done is not agreed upon by scholars since several versions of the events exist. Between 1555 and 1557, according to one version, Portuguese ships armed with cannons rid the region of troublesome pirates and in gratitude, the Chinese authorities gave the Portuguese the right to establish a trading centre on the mainland. This area was Macao, located on the peninsula of the Pearl River delta some 100 kilometres (62 miles) from Canton on the Chinese mainland. Hong Kong is located on the other side of the same estuary.

An alternative view of events is that the Chinese government was eager for trade with merchants who had access to the goods of East Africa and India. Consequently, the Portuguese were invited to establish a colony on the Macao peninsula provided they did not build any fortifications. On the other side, by investing in a permanent settlement, the Portuguese could access local goods and provide their trade ships with a useful port that could be used as a stepping stone to sail north to Japan or south to Indonesia. A Portuguese trader called Lionel de Sousa is often credited with gaining permission from Cantonese officials to set up the first private trading post in Macao. Crucially, a number of the early European traders were allowed to spend several weeks at a time in Canton to participate in its famous silk trade fairs, hosted every January and June.

Whatever the precise events leading to its establishment, unlike in other Portuguese colonies, the foundation of the Macao colony was largely thanks to traders and missionaries rather than fleets directly sponsored by the Crown. It is because of this latter fact that Macau did not become an official Portuguese colony until the early 17th century. From the early group of like-minded merchants there developed a self-governing community of householders or moradores. The Chinese authorities largely left this burgeoning community to Portuguese rule, provided the Europeans did not cause any disruption to internal Chinese affairs or trade. In return, the Chinese gained easy access to such highly desirable commodities as pepper from India, silver from the Americas and Japan, and sandalwood from Indonesia.

The port of Macao was small - it covered 5 km² (1.9m mi²) but booming, and it eventually became the most populous and successful of all Portuguese ports in East Asia. In 1601, Macao had around 600 Portuguese men - merchants, soldiers, and sailors, many of whom would have been in transit. By 1669 there were over 300 permanent Portuguese married male settlers or casados. Many of these settlers came from other colonies, especially in India.

The colonists were subject to a governor who had authority over military affairs. Political power was in the hands of the town council or câmara, an institution given its charter of privileges by the Viceroy of the Indies in Goa in 1586. In 1623, the first permanent captain of the colony of Macao was appointed, the official representative of the Portuguese king. In a reminder of the colony’s history as a merchant’s settlement, the câmara had total control of Macao’s finances and was independent in this area from the officials of the Portuguese Crown. Another source of the câmara’s power was the diplomatic situation with representatives of the Chinese emperor who would only deal with it and not the governor or any other appointed official.

A bishop was appointed as the community’s spiritual leader. In 1568, Dom Belchior Carneiro established a hospital in Macao, and a Santa Casa da Misericórdia was set up to assist the poor and pursue charity work. There was a Jesuit college, cathedral, monastery, and at least two nunneries, which offered education to orphans as well as care for disadvantaged women.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Macao was used as a base for Catholic missionaries in East Asia - especially the Jesuit order - even if the Chinese authorities made several attempts to limit the conversion of Chinese people to Christianity within the colony.

Trade

As Portugal’s empire grew, so did its trade network. Within Asia, spices and other goods were re-exchanged for gold, silver, fine textiles, and rice. Crown-licensed Portuguese ships plied their trade goods from Lisbon, Goa, and Cochin to Macao. In addition to this intercontinental trade, their presence in Macao allowed the Portuguese to participate in the lucrative South East Asia trade that was conducted between China, Japan, Malaysia, and Indonesia.

A permanent Portuguese trading presence was established at Nagasaki in Japan, and each year from 1555 to 1618, a single large cargo vessel, the ‘Great Ship’, sailed from Macao to Japan (having arrived from Goa). From 1619 to 1639 this single ship was substituted with a fleet of smaller vessels. The large carrack cargo ships that plied the route between Macao and Nagasaki had Chinese pilots but were packed with goods and Portuguese traders who appear on Japanese screen paintings of the period.

Trade ships regularly sailed from the Spice Islands (Moluccas) in Indonesia to Macao, from Goa to Macao, and from Macao to Indonesia, Siam, and Timor. Macao built up strong commercial ties with Manila in the Philippines, a trade which peaked in the 18th century. In this way, valuable commodities criss-crossed the oceans such as raw silk and silk fabrics (from China), nutmeg and cloves (Spice Islands), sandalwood (Timor), lacquer (Pegu/Bago in Myanmar), silver, painted screens, kimonos, and swords (Japan), cotton cloth, pepper, and ivory (India), cinnamon (Ceylon) and diamonds (Borneo). Macao enjoyed an almost total monopoly on certain goods such as pepper for the Chinese market and the transport of sandalwood from Timor. In the other direction, Macao sent to Goa and Lisbon such goods as Ming porcelain, mother of pearl, pearls, musk, gold, tea, and various roots and herbs from China which were considered useful medicines.

Macao Society

The merchants of Macao did very well from their trading. As in other colonies, European-born citizens formed the aristocracy of Macao, and below these were Europeans born in the empire, and below these were those of mixed race. Many of the European elite of Macao lived in great houses furnished with the finest furniture and art pieces available in Asia. Slaves, both Africans and Chinese, were used to serve in these households.

European women were rare indeed in Macao - only one was on record as an inhabitant in the 1630s, for example - and so Portuguese men married Asian women, usually slaves or ‘bought’ for the purpose, and most often Japanese or Malays. The mixed-race offspring of these marriages were very often given Portuguese names, baptised, and raised as Catholics. Portuguese was the official language, but with marriages between races there soon developed a large population of bilingual citizens. So, too, the culture became a mixed one of European and local elements, a phenomenon particularly evident in diet and clothing. Chinese nationals also traded as permanent resident merchants in the colony, and most small businesses such as shops and craft workshops which served the needs of residents were run by Chinese.

European Rivals

From the 17th century, the British and Dutch took an active interest in East Asia and challenged Portugal’s attempt to impose a monopoly on trade. Both countries formed highly efficient trading companies. In 1601, the Portuguese apprehended Dutch ships in Tidore in the Spice Islands and in Macao, executing the crews, but this did nothing except make their European rivals more determined. Both sides considered themselves at war. The Dutch took direct control of the Spice Islands at the end of the 16th century and they attacked Macao in 1622 and 1626. Causing serious problems across the Portuguese Empire, the Dutch eventually took over Malacca (1641), Colombo (1656), and Cochin (1663) so that only Macao and Timor remained in Portuguese hands in East Asia.

Relations with Japan also went sour from 1639 when the Tokugawa Shogunate ruled (1603-1868). As the military leaders of Japan grew suspicious of foreigners, all Portuguese were expelled from the country and trade halted with the likes of Macao. Macao sent delegates to the Tokugawa shogun to negotiate a reopening of trade, but these unfortunate ambassadors were executed and trade was never revived.

At least relations with China were strengthened in this period. Macao sent mercenaries on at least five expeditions to aid the Ming Dynasty in their fight against the Manchu between 1621 and 1647. However, the struggle between the Ming and Qing in China brought severe disruption to Macao in the 1650s and 1660s when coastal populations were ordered to move inland. In addition, Chinese traders were an increasing presence in Indonesia, cutting in on markets where the Portuguese had enjoyed a near-monopoly. In another blow, in 1684 the Chinese authorities permitted other European nations - essentially the Dutch, English, and French - to trade directly with Chinese merchants. The Europeans were particularly interested first in tea and then the opium trade. The Chinese were keen to control the European traders, and in 1757 they could reside in only one place in Chinese territory: Macao.

Later History

Macao continued to prosper as a trading port, even if its glory days were now but a distant memory. The colony had a population of around 30,000 in the mid-18th century, most of these being Chinese but with a significant and cosmopolitan number of Europeans and East Asians.

In 1808, Macao was briefly occupied by the British, even though it was, at least from Beijing’s point of view, Chinese territory. When the Chinese emperor received news of this incursion he sent orders to the British that they remove themselves from Macao. Unwilling to start a war with a valued trading partner and with China supplying most of the colony's food, the British - actually a force of the East India Trading Company - withdrew four months after landing.

As the 19th century progressed, British trading ships frequently stopped at Macao on their way to Canton. It was in this century that Macao really went into decline and it suffered the neglect seen in many other outposts of the Portuguese Empire. The fortunes of the colony were badly affected by the silting up of the harbour and by the rise of its powerhouse neighbour Hong Kong.

In 1951, Macao was formally made an overseas province of Portugal. In 1987, the Portuguese government agreed to hand over the colony to Chinese sovereignty in 1999 - although nobody could provide any historical document showing China had given away Macao in the first place. Part of the agreement was that the capitalist system of Macao should be allowed to continue for 50 years and so, just like Hong Kong, Macao became a special administrative region of the People’s Republic of China. In 2005, UNESCO classified the historical buildings of Macao - cathedrals, churches, and villas - as a World Heritage Site.