Protagoras of Abdera (l.c. 485-415 BCE) is most famous for his claim that "Of all things the measure is Man, of the things that are, that they are, and of the things that are not, that they are not" (DK 80B1) usually rendered simply as "Man is the Measure of All Things". Along these same lines, he also maintained that, if there were gods - as the Greeks, of course, believed - there was no way of knowing what they were like or what they might want from humanity by way of service and worship.

In maintaining this stance he pre-figures the existential relativism of writers like the 20th century CE Italian playwright, author, and philosopher Luigi Pirandello (l. 1867-1936 CE) best known for his works Henry IV, Six Characters in Search of an Author, and It is so, If you think so, by some two thousand plus years as well as every other relativist author between his time and Pirandello's.

Protagoras lived and worked in ancient Athens as a sophist, a highly paid teacher of the upper class youth of the city, who instructed his pupils in how to speak well and, especially, how to win court cases. Athens was particularly litigious and law suits were common; knowing how to turn a jury to side with one's claims was a highly prized skill and, it seems, Protagoras was very good at this.

At the same time, however, and in spite of how highly the Athenians valued his services, the cultural values of the Greeks during this time was informed by their religion and criticism of the gods was not welcome nor encouraged, much less denying their existence or claiming that, if they existed, one could not know what they were like. It is curious to consider, then, how a man who claimed that what was true to each individual was, in fact, true - regardless of any cultural values to the contrary -could come to be the most highly paid sophist in ancient Greece.

The Sophists

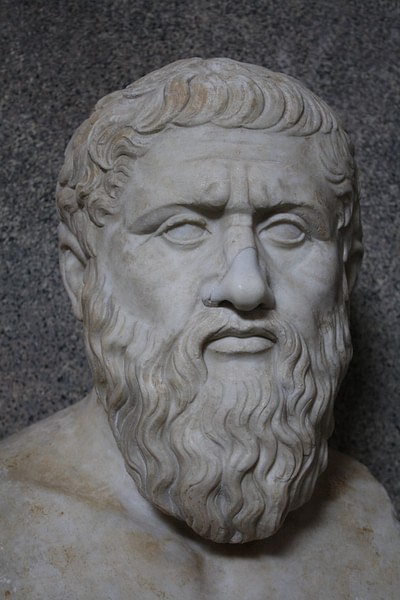

The sophists were educated men who, for a price, would teach the youth the art of rhetoric or politics and the trappings of culture (the English word sophisticated comes from the Greek sophist) in order that they might impress others with their refined manners and do well in careers in politics or whatever else. Although looked down upon by Plato (from whom we get many accounts of the teachings of various sophists, most of them unfavorable) the sophists provided a valuable service to the aristocracy of Athens, especially in that they claimed to be able to provide young men with the sort of education that would give them advantage in Athenian politics and commerce. In his Apology, Plato has Socrates scorn this practice saying how public education in Athens could produce the same results as the sophists do far more easily and cheaply.

However that may be, the sophists were popular among the Athenian youth whose fathers valued their services enough to pay them handsomely. The sophists, according to Plato, were able to "make the worse appear the better cause" and this kind of skill was handy in lawsuits as well as in constructing political speeches and discrediting political adversaries. Almost all of what we know of Protagoras comes from Plato, who completely rejected his relativism and, although Plato may be presenting a highly prejudicial view of the man, his work remains the primary sources modern day scholars have to work with.

Protagoras in Plato

Plato was the student of Socrates and developed a philosophy with the central value of the existence of Truth. There had to be an Ultimate Truth in order for any "truths" in life to be True. If everything was only opinion, as Protagoras claimed, then there was no truth whatsoever and one could believe whatever one wished to and be correct in that belief; this claim was absolutely intolerable to Plato. In the dialogue of the Theatetus, Plato argues against Protagoras' view through his central character of Socrates delivering the following criticism:

If what each man believes to be true through sensation is true for him - and no man can judge of another's experience better than the man himself, and no man is in a better position to consider whether another's opinion is true or false than the man himself, but...each man is to have his own opinions for himself alone, and all of them are to be right and true - then how, my friend, was Protagoras so wise that he should consider himself worthy to teach others and for huge fees? And how are we so ignorant that we should go to school to him, if each of us is the measure of his own wisdom? (161B)

Plato argues, here and in the dialogue Protagoras, that it is impossible for everyone to know the truth of a matter if everyone's opinions of that truth differ, often dramatically. If ten people are in a room and all ten have a different interpretation of that room then the room cannot possibly exist in objective reality but only in the individual minds of the ten people. In this same way, Plato would argue, if ten people have different interpretations of what Truth is, there can be no truth, there can only be opinion.

What Protagoras seems to be saying, however, is that the apprehension of truth is relative to individual perception and what one recognizes as 'true' will be True to that individual despite any evidence to the contrary, even if there is an objective room or an Objective Truth. In Protagoras' view, an Objective Truth is actually irrelevant because it cannot be apprehended unless an individual chooses to do so.

Protagoras' Claim in Depth

As noted, Protagoras is best known for his claim, "Of all things the measure is man, of the things that are, that they are, and of things that are not, that they are not." Although the phrase may seem simple enough on the surface to suggest complete relativism (as it is almost always interpreted), there is no way of knowing whether this is what Protagoras intended. Only a few fragments of Protagoras' work have survived and, of them, none shed any real light on the intended meaning of the phrase.

The fragment in which he is said to question the gods, however, serves as an illustration of how Protagoras' central claim may be misinterpreted. Protagoras writes:

About the gods, I am not able to know whether they exist or do not exist, nor what they are like in form; for the factors preventing knowledge are many: the obscurity of the subject, and the shortness of human life. (Baird, 44)

In this passage, Protagoras is not claiming that the gods do not exist, only that he cannot say, based on his subjective experience, whether they do. The passage can as easily be interpreted as him saying, "I do not know enough about this topic to render an intelligent opinion on it" as any statement concerning the existence or non-existence of deities.

In the same way, "man is the measure of all things" could simply mean that, although objective reality exists and an Objective Truth may even exist, these things will be interpreted and understood differently by each person experiencing them. This does not deny the truth of objective reality; it only questions the possibility of uniform interpretation of that reality. As each individual is only possessed of a certain intelligence and talent of interpretation of their surroundings, to claim that everyone will interpret an experience in the same way is unrealistic. The best example of this, not only in the modern day but throughout time, is the testimony of witnesses to a crime; everyone present witnessed the same event but each person's memory and interpretation of that event will invariably differ.

The example most often used, however, as to do with temperature of a room. An individual who is used to a warm climate might experience a room as feeling cold while one from a cold climate will feel it is warm. There is no way to objectively tell these two people that they are wrong because they are experiencing the room based on their pasts and what they have come to interpret as "warm" and "cold" so, in Protagoras' view, they would both be correct.

Whether a room is objectively cold, then, can never really be known since the experience of being cold is entirely subjective. This same paradigm, of course, extends to Protagoras' passage on knowledge of the gods. Claiming that gods exist and that one knows what they want is subjective in that the ten other people in the room may have a vastly different understanding of the divine. Arguments over the superiority and truth of one religious view over another, then is ultimately futile and pointless because there is no way someone holding to their subjective claim of "knowing God" will accept the view of another who dismisses that claim. In this, as in all else, the individual is the final measure of what is true or false.

Two thousand years after Protagoras lived and wrote, these ideas would be developed by Pirandello in his short stories and plays which consistently have as their theme this very claim by Protagoras. Pirandello noted that the problem people had with understanding each other lay in words. People used words in the belief that others would understand those words in exactly the same way the speaker meant but, after experiencing multiple misunderstandings, one understood that this was not so. The meaning Person A puts into a word or phrase is not always understood by Person B or Person C; if it were otherwise, Pirandello points out, one's understanding of reality would match perfectly with every other and there would be no disagreements.

Conclusion

Not surprisingly, considering the importance the Athenians placed on the concept of eusebia (piety, loosely translated) Protagoras was charged with impiety and drowned in the sea while fleeing for safety to the colony at Sicily. His practices and teachings were used as a model for the `Socrates' character by the playwright Aristophanes (l.c.460-380 BCE) in his play The Clouds which depicted Socrates inquiring into the gods' existence and questioning the basic values of Greek society. The character had nothing to do with the historical Socrates, however, and was actually making fun of natural philosophers and sophists like Protagoras.

At Socrates' trial for impiety in 399 BCE, when he was accused of corrupting the youth of Athens through his teaching and denying the existence of the gods, the understanding the jury had of his character from The Clouds was cited by Socrates, defending himself, as posing a great threat to his case in that the jury would remember that character and judge him according to the play, as well as by what his detractors were saying, instead of really hearing the words of his defense. Socrates was correct in this in that the jury did, in fact associate him with the sophistry of Protagoras and, although they had previously condemned Protagoras' relativism, in sentencing Socrates, they proved the sophist's most famous claim correct.