The sophists in ancient Greece were a class of teachers who, for a fairly high fee, would instruct the affluent youth in politics, history, science, law, mathematics and rhetoric as well as the finer points of grammar and history. They professed to be able to make a young man suitable for political office and, of equal importance among the litigious Greeks of the time (especially in Athens) to be able to make a strong case, whether in prosecution or defense, in court.

These teachers traveled from city to city giving lectures, taking on pupils, and debating topics publicly (this last, perhaps, as advertisement for their skills in oratory and disputation). They are almost uniformly depicted unfavorably in the philosophical dialogues of Plato (l. 428/427-348/347 BCE) as predatory frauds who preyed on the ignorant upper-class young men of Athens and extracted large sums of money from their parents in exchange for skills, in Plato's view, which they could have as easily learned through public education for free.

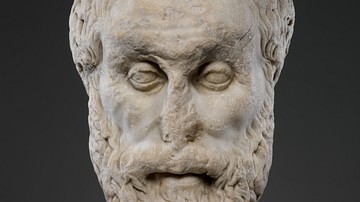

Although Plato had no kind words for any sophist, the one he seems to have despised the most was Protagoras of Abdera (l. c. 485-415 BCE), the relativist philosopher best known for his claim that "man is the measure of all things". To Protagoras, experience was relative to the individual and the objective truth of any matter was of no consequence because "truth" was defined by individual interpretation.

Little is known of Protagoras' life or thought as all that is left of his works are fragments cited by later writers but his legendary legal skills are illustrated in the model known as Protagoras' Paradox which scholars in the present day still cite and has come to be known as the Paradox of the Court.

Plato and the Sophists

Plato regularly criticized the sophists of ancient greece. This may be because, as the young poet Aristocles (Plato was his nickname), his parents patronized them for his own education or, perhaps, because one of these sophists, Critias (l. c. 460-403 BCE), was his mother's cousin, an early student of Socrates (l. 470/469-399 BCE), and became one of the Thirty Tyrants of Athens who overthrew the democracy, casting Socrates in a poor light as his former mentor.

At one point or another, Plato criticizes all the best-known sophists such as Gorgias (l. c. 427 BCE) who claimed that what people define as "knowledge" was nothing more than opinion and actual knowledge was unknowable and, if known, uncommunicable. The sophists often seem to have indulged in relativistic claims in order to advertise their skills in turning arguments to their favor and winning clients who would pay well for their sons to learn just such skills.

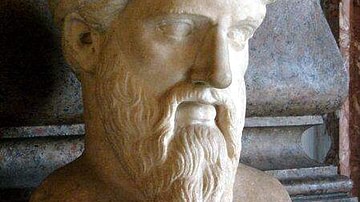

Among the most best-known sophists featured unfavorably by Plato is Thrasymachus (l. c. 459-400 BCE). In Plato's Republic, Book I, for example, Thrasymachus debates Socrates on the meaning of justice, claiming it is only the advantage of the stronger, and does so in a semi-public forum, a gathering at the house of Cephalus, father of Plato's friends, following the Panathenaic Festival. Thrasymachus is depicted as an intellectual bully who tries to trick Socrates into admitting that "justice" has no other real definition than the stronger defeating the weaker. Plato then shows Socrates proving him wrong and winning the argument.

One of the charges Plato makes against the sophists, as noted, is that they charged fees - usually high fees - for teaching students what they could have learned in the public schools. Prior to the establishment of the sophist's profession, sages gladly taught others what they knew for free.

Protagoras and his Paradox

The man named as the first sophist, and certainly the most famous, was Protagoras of Abdera (l.c.485-415 BCE) best known, as noted, for his claim that “Man is the Measure of All things” as well as that the gods' existence could neither be proven nor disproven. While Protagoras, like those who followed him, charged exorbitant fees for his services, a story is told of how the great Sophist was once outsmarted by one of his pupils and this tale has come to be known as Protagoras's Paradox.

Protagoras agreed to instruct a poor young man, Euthalos (from a working-class family) in law and rhetoric free of charge on the condition that he would pay the sophist's fee in full if, and only if, he won his first court case. Once Euthalos had completed his course of study with Protagoras he assiduously avoided taking any cases at all. Protagoras, finally out of patience with the young man, took him to court for payment and argued thusly:

If I win this case, Euthalos will have to pay me what he owes me. If I do not win this case then Euthalos will still have to pay me because, under our agreement, he will then have won his first court case. Therefore, no matter what the outcome, Euthalos will have to pay me.

Euthalos, however, contested this claim, stating:

If I win this case I will not have to pay Protagoras, as the court has declared his case invalid. If I do not win this case I still do not have to pay as I will then have not won my first court case. Therefore, no matter what, I do not have to pay.

This argument (for which no solution was ever offered in antiquity) has come to be known as the Paradox of The Court (L. Alqvist) and a resolution to the question is still debated today in law schools as a logic problem.