The Land of Punt was a region in Africa (most likely Somalia) referenced by inscriptions of ancient Egypt initially as a partner in trade and, later, as a semimythical country rich in resources and exotic goods. It is best known from the inscriptions of Queen Hatshepsut (r. 1479-1458 BCE) though trade had been established much earlier.

In the decades after Jean-Francois Champollion first deciphered Egyptian hieroglyphics in 1822, and western scholars began reading Egyptian texts, questions arose as to where Punt was located and what it was called in the modern era. Punt was probably located in the modern-day region of North West Somalia based on the similarity between the ancient city of Opone referenced by ancient works and the modern city of Pouen, Somalia. The Egyptians called Punt Pwenet or Pwene which translates as Pouen known to the Greeks as Opone. It is well established that Opone traded with Egypt over many centuries. Even so, modern scholarship continues to debate Punt's location.

As noted, the country is best known from inscriptions regarding Queen Hatshepsut's famous expedition in 1493 BCE in the 18th Dynasty of Egypt. This exchange between the two countries brought back living trees to Egypt, marking the first known successful attempt at transplanting foreign fauna. This voyage to Punt is only the most famous, however, and evidence suggests that the Egyptians were trading with the Land of Punt as early as the reign of the pharaoh Khufu in the Fourth Dynasty of Egypt (c. 2613-2498 BCE) and probably earlier.

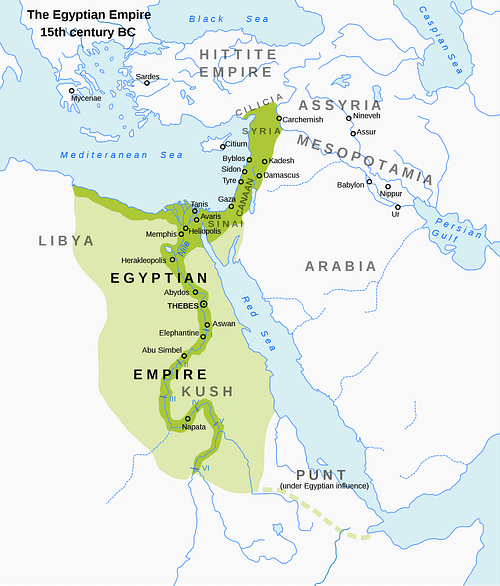

Egypt grew as a nation as trade increased beginning in the latter part of the Predynastic Period (c. 6000-3150 BCE). By the Early Dynastic Period of Egypt (c. 3150-2613 BCE) trade was firmly established with regions in Mesopotamia and Phoenicia. By the time of the Fifth Dynasty (c. 2498-2345 BCE), Egypt was flourishing through trade with these areas and especially the Phoenician city of Byblos and the countries of Nubia and Punt.

Location of the Land of Punt

As noted, the exact location of the Land of Punt is still disputed by historians, scholars, archaeologists, and others in the present day. Through the years it has been cited as part of Arabia, present-day Somalia or the Puntland State of Somalia at the Horn of Africa, Sudan, Eritrea, or in the present region of the de facto independent Republic of Somaliland but could refer to some other internal region of east Africa. The debate continues as to where Punt was located, with scholars and historians on every side offering plausible supports for their claims. The two best possibilities are Eritrea and North West Somalia with Eritrea so far gaining the most widespread acceptance.

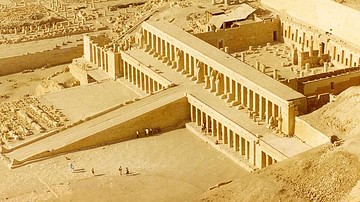

It would seem, however, from the reliefs telling of the expedition carved on Hatshepsut's temple at Deir al-Bahri, that Punt was likely located in present-day Puntland State of Somalia or, at least, North West Somalia. The culture of Puntland State of Somalia bears a number of striking resemblances to that of ancient Egypt including language, ceremonial dress, and the arts, suggesting ancient cross-cultural exchange.

Scholar John A. Wilson writes how Hatshepsut was very proud of the expedition she launched to Punt and he makes clear that it was "the land of incense to the south, perhaps chiefly in the Somaliland area, but also Arabia Felix" (176). Wilson seems to favor an interpretation of Somalia as Punt when he points out the "unusual prominence" of this expedition and the route the Egyptians seem to have taken to reach it.

Punt could not have been in Arabia because the Egyptians traded regularly with that region which was not "to the south" and could not have been Nubia because the Egyptians knew that land well also and an expedition there would not have been represented as exceptional. Further, trade with Punt involved sea travel which rules both of those out. It is possible it was located above Somalia in Eritrea, however, and this region is the best contender for Punt after Somalia.

Those who favor an interpretation of Somalia as Punt point to Hatshepsut's description of the expedition as well as earlier references. The Egyptians traveled there by boat down the Nile, through the Wadi Tumilat in the eastern Delta and on to the Red Sea. There is evidence that the Egyptian crews would disassemble their boats, carry them overland to the Red Sea, and then hug the shores as they made their way to Punt.

While this description does favor an interpretation of Eritrea, the other evidence weighs heavily in favor of North West Somalia. The Egyptians would have hugged the coast all the way to the Horn of Africa, present-day Puntland State of Somalia. Wilson cites the reliefs at Hatshepsut's temple as evidence of how amazed the Puntites were at the Egyptian's arrival as they were, seemingly, at the edge of the world. Wilson writes:

The people of Punt are flatteringly amazed at the boldness of the Egyptian sailors: "How did you reach here, the country unknown to men? Did you come down on the ways of heaven or did you travel by land or sea? How happy is God's Land (Punt), which you now tread like Ra!" (176)

Punt is also represented as quite foreign to the Egyptians. Scholar Marc van de Mieroop writes:

[The Egyptians] reached Punt by seagoing boat and found it a country very unlike their own. The representations of houses, animals, and plants suggest a location in northeast Africa along the Red Sea coast, possibly the region of modern Eritrea, although a locale farther inland has also been suggested. (169)

Wherever it was, the reputation of the land as rich in resources was already established prior to Hatshepsut's expedition. Scholar Rosalie David notes:

The Egyptians had a constant demand for incense and myrrh - Punt's prime products - for their temple services and had known of the existence of this land since Dynasty 5. Expeditions had been sent there since the late Old Kingdom. (267)

While trade between Egypt and Punt is well-established, and evidence supports the Somalian connection to Punt, there still remains no scholarly consensus on location.

The Hatshepsut Expedition to Punt

Although the two countries had a long history in trade, the 1493 BCE expedition of Hatshepsut was given particular significance. This may be simply because this transaction was larger than any other but evidence suggests the way to Punt had been lost and Hatshepsut was directed by the gods to re-establish the connection. Wilson describes how the voyage was first commissioned by Hatshepsut, based on the reliefs from her temple:

Amun-ra of Karnak spoke from his sanctum in the temple and directed Hat-shepsut to undertake the commercial exploration of the land of Punt. "The majesty of the palace made petition at the stairs of the Lord of the Gods. A command was heard from the Great Throne, an oracle of the god himself, to search out ways to Punt, to explore the roads to the terraces of myrrh." (169)

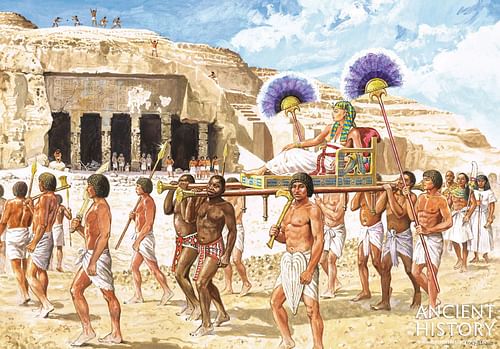

Hatshepsut then commanded that the will of the god be done and five ships were outfitted for the journey while goods were gathered for trade. Historian Barbara Watterson describes the journey based on the inscriptions from Hatshepsut's reign:

Five ships set out from a port on the Red Sea (possibly Quseir) to journey southwards to Suakin, where the expedition disembarked. The voyage had taken between 20 and 25 days, covering on average about 50 kilometers a day, with the ships hugging the coast rather than risk the dangerous deep water of the Red Sea. From Suakin, the route to Punt was overland through the Red Sea hills. (101)

This description of an overland voyage to Punt following the passage down the Red Sea can argue for either Eritrea or Somalia but, again, must be weighed along with the other evidence. Wherever its exact location near the Horn of Africa, it was very highly regarded and sufficiently different from Egypt to lend itself to mystery. The villages of Punt are described as houses set on stilts and governed by a king who may have been advised by elders. Inscriptions indicate relations between the two countries were very close and the Puntites an extremely generous people. The Land of Punt is praised for its riches and the "goodness of the land" by Egyptian scribes.

Egyptian Trade with Punt

A Fourth Dynasty relief shows a Puntite with one of Pharaoh Khufu's sons, and in the Fifth Dynasty documents show regular trade between the two countries enriching both. A tomb inscription of the military commander Pepynakht Heqalb, who served under the king Pepy II (2278-2184 BCE) of the Sixth Dynasty of the Old Kingdom of Egypt, narrates how Heqalb was sent by Pepy II to "the land of the Aamu" to retrieve the body of the warden of Kekhen who "had been building a reed boat there to travel to Punt when the Aamu and Sand-dwellers killed him" (van de Mieroop, 90).

The Aamu were the Asiatics of Arabia and the Sand-dwellers those of the Sudan, arguing for a departure point for Egyptian trade around the port of Suakin (as previously noted by Watterson) on the west coast of the Red Sea. Egyptians relied on trade with Punt for many of their most highly prized possessions.

Among the treasures brought to Egypt from Punt were gold, ebony, wild animals, animal skins, elephant tusks, ivory, spices, precious woods, cosmetics, incense and frankincense and myrrh trees. Watterson writes, "In return for a modest present of a few Egyptian weapons and some trinkets, the Puntites gave their visitors sacks of aromatic gum, gold, ebony, ivory, leopard skins, live apes, and incense trees" (101).

Trade between Egypt and Punt was not as one-sided as Watterson suggests, however, as the inscriptions make clear fair exchange by both parties. Wilson reports how the Egyptians arrived at Punt with "jewelry, tools, and weapons" and returned with "incense trees, ivory, myrrh, and rare woods" (176). There is also evidence the Egyptians traded metals available in their country for the gold of Punt even though Egypt had its own gold mines. Rosalie David describes a scene involving trade goods from the expedition of Hatshepsut as given in the inscriptions from her temple at Deir al-Bahri:

The illustration shows that the incense has been piled up in front of the Egyptian ambassador and his soldiers while monkeys and panthers are led forward; the Egyptian "exchanges" - daggers, axes, and necklaces - are set out on a table, and when the deal is agreed, the Puntite officials are taken to the tent of the Egyptian envoy and presented with gifts of bread, beer, wine, fruit, and meat. The accompanying inscriptions attempt to explain, however, that these weapons used in barter by the Egyptians were actually an "offering" for Hathor, the goddess of Punt. Next, the goods were weighed and measured and loaded onto the ships for the return journey. In this instance, these included heaps of incense, myrrh trees, ebony and ivory, gold, scented woods, incense, eye pigments, monkeys, baboons, dogs, and panther skins. They were eventually presented to Queen Hatshepsut at Thebes, and great delight was expressed particularly with the trees that were subsequently planted in the temple garden. (267-268)

The myrrh trees mentioned were an especially impressive article of trade. As noted, this exchange is the first time in recorded history that fauna (plants and trees) was successfully transplanted in another country. This transplant was so successful the trees flourished in Egypt for centuries. The roots of the trees brought back from Punt by Hatshepsut's expedition in 1493 BCE can still be seen outside of her complex at Deir al-Bahri.

Inscriptions on the walls of the site detail the Egyptian relationship with Punt and make clear that it was a mutually beneficial one and both parties held the other in deep respect. Reliefs on the walls of the temple show the chief of the Puntites and his wife receiving the envoys from Egypt with all honors. So precise are these depictions that modern-day scholars have been able to diagnose the Puntite wife of the Chief, Aty's, medical problems. According to historian Jimmy Dunn, the queen "shows signs of Lipodystrophy, or Dercum's Disease. She has a pronounced curvature of the spinal column" (3). The inscriptions mention King Perehu of Punt and his generosity which, judging from the goods brought back to Egypt, was vast.

Hatshepsut's reign was among the most prosperous in Egyptian history, but it is clear that she considered her expedition to Punt among her greatest successes. Watterson describes the importance of Punt to the queen in discussing the reliefs at the temple of Deir al-Bahri:

Reliefs depicting important themes from Hatshepsut's life decorate walls in the colonnades: her birth, the transportation of obelisks for the Temple of Amun in Thebes, the great expedition to Punt. (161)

Marc van de Mieroop also comments on this, writing:

Among the goods imported were complete incense trees as well as loose incense, an expensive fragrant tree extract that was used in [religious services] as an offering to the gods. The expedition gathered enormous heaps of it and the accompanying inscription asserts that such amounts had never before been acquired. The relief's prominence indicates how proud Hatshepsut was of the expedition's achievements. (169)

Thirty-one incense trees (Boswellia) were brought back to Egypt, in addition to all of the other valuable goods mentioned above, but it seems as though visiting Punt was just as important as the trade goods exchanged.

The Land of Punt was long associated with the gods and Egypt's legendary past partly because so many of the materials from Punt were used in temple rituals. The leopard skins from Punt were worn by priests, the gold became statuary, the incense was burned in the temples. A deeper association, however, sprang from the belief that the gods who blessed Egypt had equal affection for Punt. Hatshepsut's inscriptions claim the goddess Hathor came from Punt and there is evidence that one of the most popular Egyptian gods of childbirth, Bes, (known as the Dwarf God) was also associated with the region.

Conclusion

In the 12th Dynasty (1991-1802 BCE), Punt was immortalized in Egyptian literature in the very popular Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor in which a castaway Egyptian sailor on an island converses with a great serpent who calls himself the "Lord of Punt" and sends the sailor back to Egypt laden with gold, spices, and precious animals. The sailor in the story tells his master the tale to cheer him up after a failed expedition. He points out how his master may feel disappointed at his recent failure but how he once experienced a similar failure himself, only worse: his ship was actually lost and, alone in a strange land, he feared for his life until reassured by the Lord of Punt.

Punt is purposefully chosen in this story as the mystical land on which the sailor washes up because it was already understood as a faraway realm of exotic goods and generous people. The sailor is telling his master that, even though life may look bleak at a certain time, good can come out of even the darkest moments in life. He holds up the example of the Lord of Punt sending him home a richer man than when he had set out on his doomed voyage as the name of Punt would have reminded the master of the gods and their blessings, as evidenced by the riches of Punt brought back to Egypt, and would have reminded an audience hearing the tale of the same.

The Land of Punt eventually became a semimythical land to the Egyptians but was still understood as a very real place through the New Kingdom of Egypt (1570-1069 BCE). The vizier Rekhmira mentions accepting tribute from foreign delegations from Punt during the reign of Amunhotep II (1425-1400 BCE). Punt is mentioned during the reign of Ramesses II (the Great, 1279-1213 BCE) and that of Ramesses III (1186-1155 BCE).

Punt came to hold a deep fascination for the Egyptian people as a "land of plenty" and was known as Te Netjer, the land of the gods, from which important goods came to Egypt. Punt was also associated with Egyptian ancestry in that it came to be seen as their ancient homeland and, further, the land where the gods emerged from and consorted with each other. Exactly why Punt was elevated from reality into mythology is not known but, after the reign of Ramesses III, the land receded further and further in the minds of the Egyptians until it was lost in legend and folklore.